SEKINO Jun'ichirô (関野準一郎)

|

|

| Sekino: Reclining nude, self-printed woodcut, 1941 (image: 652 x 827 mm; paper: 713 x 887 mm) |

Sekino Jun'ichirô (関野準一郎), a leading artist in the sôsaku hanga ("Creative prints": 創作版画) movement, produced some of the finest portraits and figure studies in twentieth-century Japanese art. A masterful printmaker excelling in many techniques, he worked with intaglio media (etching, drypoint, aquatint, mezzotint, engraving), planar media (lithography), carved media (woodcuts, wood engravings), and mixed media (collagraph, found objects, textile printing). Quite often, he made preparatory sketches, in graphite, watercolors, or oils. He also produced finished watercolors and oil paintings.

Interested in both traditional and modern art, Sekino admired ukiyo-e artists such as Tôshûsai Sharaku (active c. 1794-95), and benefitted from his associations with the modernists Munakata Shikô and Onchi Kôshirô. Sekino also praised the work of European artists such as Rembrandt, Munch, Dufy, Lautrec, Zorn, and Kollwitz. The influence of Western art is aptly demonstrated in the design shown above from 1941. Sekino’s nude reclining on a divan portrays a Japanese beauty in a style aligned with the idiom of European studies and paintings of the nude female form. It is the only known impression, although a full-size monochrome preparatory drawing has also survived. The spirited printing features bravura layering and texturing of pigments, soft and irregular edges of forms, and a background glistening with sprinkled mica. The very large format was made possible by a new development in Japan for print media — plywood faced with solid Japanese woods whose augmented scale liberated printmakers from the compositional constraints of traditionally smaller planks of solid cherry wood (sakura). The charming, demure nude and exuberantly printed surface call forth an emotional response from the viewer. For a woodcut, the scale is monumental, the technique painterly, and the expression intimate and nuanced.

|

| Sekino: Iizaka Onsen (Iizaka Hot Spring: 飯坂温泉), self-printed(?) woodcut, 1932 Print no. 7 of 16 from vol. 12 of Hanga shi Chôkokutô (Print Magazine Carving Knife: 版画誌 雕刻刀) (image: 132 x 175 mm; paper: 205 x 305 mm) |

It appears that Sekino's first published works appeared in 1931 in [Hanga shi] Chôkokutô ([Print Magazine] Carving Knife: 版画誌 雕刻刀) published by the Sôsaku Hanga Kenkyûkai (Creative Print Research Group: 創作版画研究会) under the leadership of Satô Yonejirô in Aomori (青森). There were 17 issues from June 1931 to December 1932, each limited to 30 copies. It was soon revived from January 1933 to June 1934 (13 issues) and again from October 1938 to June 1939 (8 issues) as Mutsu goma ("Aomori Horse"). Issue 6 added "Hanga shi" to the title on the covers. The number of designs varied per issue from as few as 12 (vols. 13 & 17) to as many as 29 (vol. 2) and even 60 (vol. 6 ex-libris), plus designs for the covers. Sekino contributed designs for volumes 9-12 and 14-16. An example from volume 12 (1932) is shown immediately above, as issued, mounted to the original coarse-fiber backing paper. Titled "Iizaka Hot Spring" (Iizaka Onsen : 飯坂温泉), it demonstrates the beginnings of Sekino's mastery of conventional woodcutting and printing in a style consistent with the prevailing mode favored by many sôsaku hanga artists of the period. Sekino's approach would change radically after meeting Onchi Kôshirô in 1939, and even further when he fully developed his own style of blockcutting and printing by the late 1950s. This impression of "Iizaka Hot Spring" might have been self-printed, given the somewhat looser manner than would have been typical of professional artisans working for art magazines at the time. Chôkokutô was also a small, low-budget enterprise located quite a distance (about 360 miles north) from the metropolis of Tokyo, so it is possible the contributing artists were expected to supply finished works for publication.

|

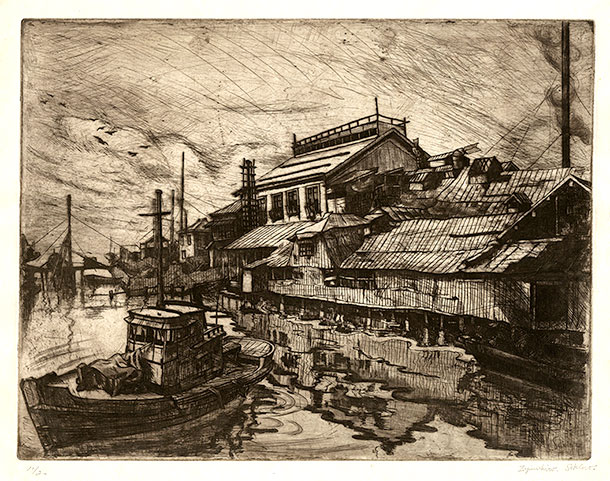

| Sekino: Aomori harbor, self-printed etching, 1936 (356 x 466 mm) |

Early on, Sekino quickly mastered the craft of intaglio printmaking and produced excellent copperplate works by the mid-1930s. One example is shown immediately above, a view of Aomori harbor under a turbulent sky. Sekino’s early etched landscapes and seascapes were realistic views in the traditional European manner. In the Aomori scene, he combined confident line work with Whistlerian-style plate tone for a dramatic setting of a boat and harbor houses under a stormy sky, with masterfully rendered reflections in the water. Years later, Sekino would operate his own etching press in the kitchen of his home and by 1951, he became head of a "copper-plate research group," through which both amateurs and seasoned printmakers had access to his press. Two years after, the loosely knit group morphed into the more official-sounding Japanese Copper-plate Print Association (Nihon Dôbanga Kyôkai: 日本銅版画協会). Among the notable participants were Hamada Chimei (浜田知明 1917-2018), Hamaguchi Yôzô (浜口陽三 1909-2000), Kobayashi Donge (小林ドンゲ born 1926), and Komai Tetsurô (駒井哲郎 1920-1976).

|

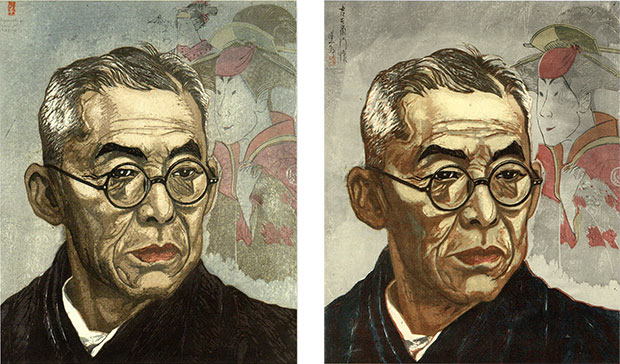

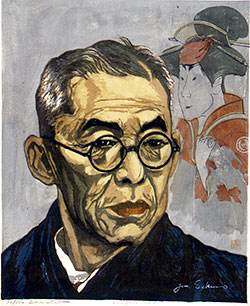

| Sekino: Portrait of the actor Nakamura Kichiemon I (初代目中村吉右衛門 1886-1954), carved and printed in 1947, with the figure of the actor Tomisaburô Segawa I as Yadorigi in Hana ayame Bunroku Soga at the Miyako-za, Edo in 1794, by Tôshûsai Sharaku. (Left) Self-printed trial proof with added figure in the background from a graffiti-style caricature of the actor Iwai Kumesaburô III (later Iwai Hanshirô VIII) in Osome Hisamatsu ukina no yomiuri (News of the affair of Osome and Hisamatsu), 1847, Ichimura-za, Edo, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861), from the series Nitakaragura kabe no mudagaki (Storehouse of treasured goods: Scribblings on the wall: 荷宝蔵壁のむだ書) (Right) Self-printed impression from early edition, numbered 19/20, with the single actor-figure in background. The inclusion of Tomisaburô in the background was, according to Sekino, meant simply to evoke the atmosphere of kabuki and to establish Kichiemon as an important theatrical figure in a long tradition of illustrious actors. |

In Sekino's reclining nude and other early self-printed woodcuts, the most obvious influence was the artist, book-designer, poet, and mentor Onchi Kôshirô (1891-1955) whom Sekino first befriended in 1939 and from whom, Sekino reported, he learned the "spirit of art." Onchi was the pivotal artist in the sôsaku hanga movement from the 1930s until his death, and when looking at many of Sekino's early large-format portraits, some of them masterpieces, one immediately recognizes elements of Onchi's style. Sekino printed some areas with Onchi-like textured colours, resulting in ‘puddling’ and striation. The splashing of colours in the margins and the rough edges and slight misregistration of forms emerge from the emotive, spontaneous Onchi-inspired approach taken by Sekino.

A much-admired example of Sekino's post-war approach to large-format portraiture is shown above and to the right, featuring the kabuki actor Nakamura Kichiemon I (中村吉右衛門 1886-1954). Sekino became friends with Kichiemon during the Second World War when the actor's kabuki troupe performed at a factory where Sekino was stationed. Although his portrait style was influenced by Onchi, by this time Sekino was a fully accomplished print designer on his own terms. He used a somewhat "drier" and more controlled method compared with Onchi's experimental, spontaneous, and "moist" approach. Sekino's technique, like Onchi's, involved soft edge overprintings (without keyblock outlines) of various shades of colors for the modeling of the face. It was a complex method requiring carved-out shallow depressions in the blocks and nuanced shading of pigments as he applied them to the blocks in multiple overprintings.

A much-admired example of Sekino's post-war approach to large-format portraiture is shown above and to the right, featuring the kabuki actor Nakamura Kichiemon I (中村吉右衛門 1886-1954). Sekino became friends with Kichiemon during the Second World War when the actor's kabuki troupe performed at a factory where Sekino was stationed. Although his portrait style was influenced by Onchi, by this time Sekino was a fully accomplished print designer on his own terms. He used a somewhat "drier" and more controlled method compared with Onchi's experimental, spontaneous, and "moist" approach. Sekino's technique, like Onchi's, involved soft edge overprintings (without keyblock outlines) of various shades of colors for the modeling of the face. It was a complex method requiring carved-out shallow depressions in the blocks and nuanced shading of pigments as he applied them to the blocks in multiple overprintings.

According to Oliver Statler, for the portrait of Kichiemon, Sekino needed 15 printing stages and used six plywood blocks of shina (basswood or Japanese linden), a soft wood with fine texture (instead of sakura or Japanese cherry, the traditional wood used for ukiyo-e printmaking, which was moderately hard). True to sosaku hanga principles, Sekino carved, printed, and published early editions of his portrait of Kichiemon. Self-printed impressions come from an edition of 20 plus some unnumbered proofs (see images above). Later editions of 50 and 100, plus "second state" (IIme état) printings (see impression immediately right), are almost always studio-produced by artisans under the artist's supervision. The result is greater contrast in color and and less subtlety in details than in self-printed examples.

Two other early figure studies from 1948 help show how experimental Sekino could be in his explorations of the human form. Below left is a portrait of two kabuki actors applying stage makeup in their dressing room known in only two other impressions, one complete and one a trial proof. The contrast in coloring for each actor distinguishes the two figures. In the foreground, the actor applies oshiroi (face-whitening cosmetic base: 白粉) for an onnagata role ("woman's manner" indicating a male actor in a female role: 女方 or 女形). In the background, a companion actor paints on some kuchi-beni ("mouth red: 口紅) or red lipstick after having applied a version of kumadori ("Taking the shadows": 隈取), kabuki makeup with "border stripes" for a male role. The expressive shading and intimate voyeuristic view make this a memorable double portrait.

|

|

| Sekino: Preparing for performance, self-printed woodcut, 1948 (image: 587 x 465 mm; paper: 628 x 507 mm) |

Sekino: Masked musician with mandolin, self-printed woodcut circa 1948 (image and paper: 484 x 402 mm) |

Sekino was not inclined to explore abstraction; he far more frequently produced work around the edges of that genre. A very different and possibly unique (for Sekino) type of figure drawing is his masked musician with mandolin (above right). It takes its cue from Synthetic-Cubist adaptations of paper cutouts, their parts linked together in puzzle-like compositions, often flatter (less a matter of multiple views "in the round") and more colorful and fragmentary than Analytical Cubism. Sekino's design is reminiscent of Picasso’s Cubist harlequin or musician paintings, or those of his contemporaries, such as Juan Gris. Sekino deconstructs the figure into an assemblage, flattening the forms without perspective except for the mandolin and sheet music. Onchi-inspired printed string is used over the mask, torso, right arm, and mandolin, introducing movement and producing decorative web-like effects. Onchi first used string printing around 1948, so it is possible Sekino followed suit soon after that date. There are two other known impressions, one in a private collection and one in the Aomori Museum, Japan.

Signature styles help to identify self-printed editions, particularly when the letter "J" in Jun'ichirô is written without the looping curves of later signatures. When demand rose for these large portraits, Sekino did not want to spend his time printing more editions. So he employed studio artisans to do the printing, under his general supervision (he signed and sealed these impressions, so his "approval" was explicit). To a large degree, the later studio printings are less interesting compared with Sekino's own printings because they show less variety or experimentation from impression to impression. Moreover, the later papers were more absorbent than the earlier torinoko papers, tending to take the pigments in a similar manner across the entire edition. On the whole, self-printed impressions of these early large-format portraits are more complex and subtle (as in the self-printed examples at the top of this page).

|

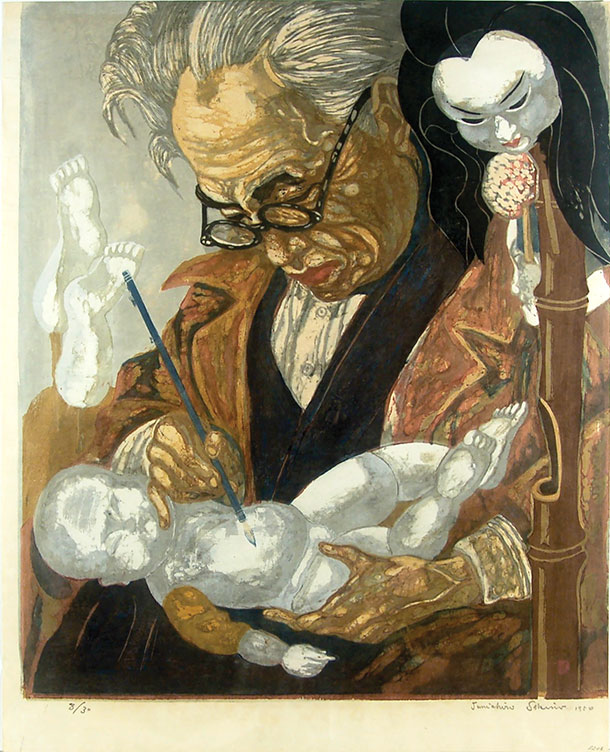

| Sekino: Ningyô sakka (doll-maker: 人形作家), 1949 (1954) Woodcut (image: 732 x 613 mm; paper: 788 x 630 mm) |

Up to around 1954, it appears that Sekino printed his large portrait designs for the early editions, whose numbered sizes were: unnumbered, 1, 5, 10, and 20. Impressions from editions of 30 are often self-printed (see image above and next paragraph), but not always. Examples from editions of 50 or more and from IIme état editions were almost always printed by studio artisans. To make verifications of self-printing even more complicated, Sekino did occasionally print some impressions for later editions, for example, when he needed an impression for an exhibition, although he did so on the more modern types of papers and usually in a manner similar to that of his artisans. Furthermore, he also occasionally used a later signature style on earlier impressions when they were sold at much later dates. With experience one can assess whether an impression is self-printed by relying on an array of factors: manner of printing (expressiveness, complexity, depth), edition size, signature, type of paper, and comparisons with known self-printed impressions.

One last example of an early self-printed design by Sekino is shown immediately above. This large-scale woodcut depicts a ningyô sakka (doll-maker: 人形作家) in his workshop painting the body of one of his creations. Various dates have been assigned to this design, including 1948, 1949, 1953, 1954, and 1956. The most commonly encountered is 1949. While the this image was issued over several years in different editions, either by Sekino or his studio, the impression (#8/30) shown here is signed with the early version of the artist's pencil signature and dated 1954 in the lower right margin. The printing is expressive and complex, serving as an example of self-printing from an edition of 30. Two other printings from this same edition are in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 7/30 and 11/30, acquired in 1954 and 1955, respectively, although dated on their website to 1949, presumably guided by Kawabara Sumio, #90 (see ref. below). There is also a 1956 pencil-dated impression from an edition of 50 that was once in the Juda Collection (see Christie's ref. below). All impressions from this later and larger edition seem to be studio printed. All this being said, Sekino was usually consistent when inscribing dates on his prints, typically using the dates that the blocks were carved, even on obviously much later printed impressions. However, as discussed above, in some instances Sekino varied the inscribed dates, sometimes using the date of printing or the year the particular impression was sold. The lack of top and right-hand margins is not, in this instance (and in a few other impressions of this design) an indication of trimming. The entire image remains intact and the absence of the two margins was presumably intentional, possibly resulting from the manner in which the paper was aligned during printing of early impressions.

|

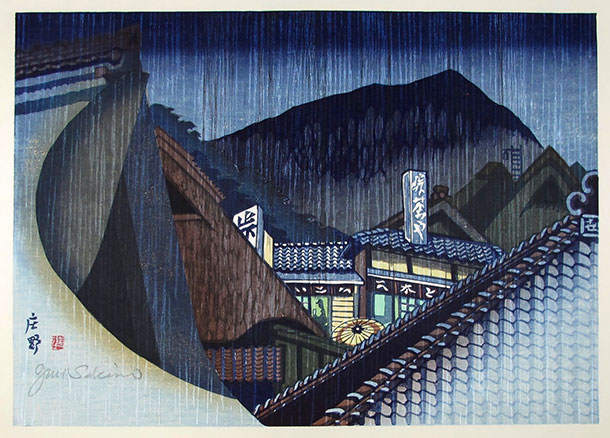

| Sekino: Shôno, July 1962 (image: 323 × 458 mm; paper: 421 × 547 mm) Series: Tôkaidô gojûsan no tsugi: (Fifty-three stations of the Tôkaidô: 東海道五十三次) |

The most familiar of Sekino’s landscape series is his interpretive updating of a popular Edo-period theme, the "Fifty-three stations of the Tôkaidô" (Tôkaidô gojûsan no tsugi: 東海道五十三次). Sekino carved the blocks from 1960 to 1974 and printed the test proofs for large, unnumbered editions. The paper (watermarked "Jun Sekino") was printed on the smooth side, which faces the drying board during manufacture. It was an Echizen washi called "kizuki hôsho" made by Iwano Ichibei VIII (1901–1976), designated a "Living national treasure" (Ningen kokuhô) in 1968 by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs. Printing was divided among Kobayashi Sôkichi, Yoneda Minoru, and Iwase Kôichi. Sekino signed and sealed all impressions meeting his approval. Upon his completing the series in 1974, all 55 designs (the starting and ending desintation, Nihonbashi and Kyoto, are also included in the series) were reissued for exhibitions. In 1975, Sekino received Japan's Ministry of Education Award, acknowledging his "maturity in using every possible technique in woodblock printing, Japanese traditional art, and the recreation of the old fifty-three stations of the Tôkaidô highway in the light of the present day." His design for Shôno is shown above. It is typical of many designs in the series, which offer unusual vantage points of particular scenes. Here, an aerial view from above the rooftops provides a glimpse of a traveler seated inside an inn. His umbrella can be seen outside the doorway as a heavy downpour soaks the houses and street. Sekino references the famous design by Utagawa Hiroshige by adapting several elements: the use of strong diagonals, the sheets of rain, and the silhouetted bamboo bending in the wind. The impression shown here is quite fresh, with the band of yellow pigment still strong as it follows the curve of the roof at the lower left.

|

|

| Zephyrus, God of Winds, and the gentle breeze Aura Copperplate etching, 1949 Venus no tanjô, Dôbanga-shû (ヴイナスの誕生 銅版画集) Shown here cropped to plate mark |

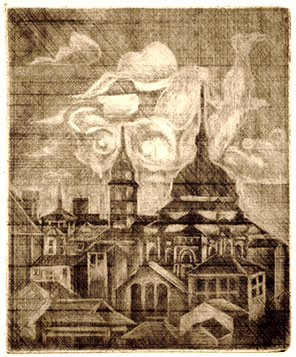

Nude in the sky Copperplate etching, 1949 Venus no tanjô, Dôbanga-shû (ヴイナスの誕生 銅版画集) Shown here cropped to plate mark |

Sekino was a prolific illustrator of books, for which he produced many hundreds if not thousands of images. Some of his finest books were self-printed and privately issued. Counted among the best of these for its elegant production quality and imaginative pictorial choices was his 1949 Venus no tanjô, Dôbanga-shû (Birth of Venus, Collected copper prints: ヴイナスの誕生 銅版画集). Printed in an edition of 100, the first 30 numbered books were self-printed, while the remaining copies (nos. 31-100) were studio printed. Each of the 10 intaglio prints is accompanied by a elaborately laid-out page of information, each arranged against a fanciful linear design. In the example shown above left, Sekino has reworked a detail from the left side of Sandro Botticelli's (c. 1445-1510) celebrated painting on canvas titled the "Birth of Venus" (1485, Uffizi Gallery, Florence). Sekino added a view of a buildings in a small town, surrounded by a strange grouping of hills that have an anthropomorphic aspect and, indeed, appear to depict a woman's right leg and left hip and knee. The figures in the sky, which come close to Botticielli's originals, are Zephyrus, God of the West Wind, and the deity Aura representing the "gentle breeze" of early morning. In another plate (shown above right), Sekino presents a town seen below clouds that take on the shape of a reclining female nude. This sort of transformation of natural phenomena into human forms is indicative of Sekino's tendency to introduce surrealism into some of his imagery, especially among the many illustrations he produced for books. © 2021 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Aomori Museum of Art (Aomori Kenritsu Bijutsukan: 青森県立美術館), ed. Akira Kanno (担当菅野晶): Sekino Jun'ichirô ten: Seitan hyakkunen (Exhibition of Sekino Jun'ichirô: 100th Anniversary of His Birth": 関野準一郎展 ・ 生誕百年), Oct. 4 to Nov. 24, 2014 (exhibition catalog, 231 pp.).

- Christie's: The Helen and Felix Juda Collection of Japanese Modern and Contemporary Prints. New York: Christie's, April 22, 1998, lot no. 387.

- Fiorillo, John: "The art of Sekino Jun'ichirô: Expressive realism and geometric formalism," in: Andon 104, Fall 2017, pp. 73-93.

- Kuwabara, Sumio: "The print world of Sekino Jun-ichirô," in: Jun-ichirô Sekino, the prints; Japanese title: Sekino Jun-ichirô hanga sakuhinshû (Collected print works of Sekino Jun’ichirô). Tokyo: Abe Shuppan, 1994 (1997 edition).

- Martin, Elias: Behind Paper Walls: Early Works and Portraits by Jun'ichirô Sekino. Chicago: Floating World Gallery, 2010.

- McClain, Robert & Yoko: Thirty-six Portrait Prints by Sekino Jun'ichirô. Eugene: University of Oregon, 1977.

- Merritt, Helen: Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints. The Early Years. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990, pp. 239-242.

- Sakai, Tetsuo et al.: Mô hitotsu no Nihon bijutsushi kin gendai hanga no meisaku 2020 (Another History of Japanese Art: Masterpieces of Modern and Contemporary Prints 2020: もうひとつの日本美術史近現代版画の名作2020). Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama, 2020, p. 117, nos. 7-9, 7-10.

- Sekino Jun’ichirô, My printmaking teachers: Biographies of modern Japanese print artists (Waga hangashitachi: Kindai Nihon hanga kaden, わが版画師たち 近代日本版画家伝). Tokyo: Kôdansha, 1982.

- Sekino Jun’ichirô: Carving people: A collection of 50 years of Sekino's block prints (Ningen o horu Sekino hanga gojûnen no shûtaisei). Tokyo: Bunka Shuppan Kyoku, 1981.

- Statler, Oliver: Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn. Rutland & Tokyo: Tuttle, 1956, pp. 63-70 and 192-194.

Viewing Japanese Prints |