YOSHIDA Tôshi (吉田遠志)

|

Yoshida Tôshi (吉田遠志 1911-1995) was the eldest son of Yoshida Hiroshi (1876-1950) with whom he studied from the age of fourteen. From 1932 to 1935, he also enrolled at the Taiheiyo-Gakai (Pacific Painting Association) which had been co-founded by his father. Before the Pacific War, Tôshi traveled widely with his father in Asia, Europe, Egypt, and the United States. In subsequent years, he continued to travel on his own, especially in Mexico, the United States, Canada, and Africa. He remained in his father's studio (established in 1925) until Hiroshi's death in 1950 and ran the family operations thereafter. Tôshi's eldest son (Yoshida Tsukasa, 芳田司 born 1949) is also a printmaker in the family tradition.

|

| Yoshida Tôshi: "Dance of Eternal Love," 1994 Alternate title, in Japanese, Seirei no mai (Dance of pure serenity: 清麗の舞) Woodcut, unlimited edition, pencil signature, image: 330 x 445 mm |

With the death of his father, Tôshi became the head of the family, initially focusing on restoring their finances, which had suffered after the war. He took on the leadership of the Yoshida studio, promoting his father's work while encouraging expansion of the idiom that his father had established. He also supported experimentation in a more modern, international style, as could be found in his brother Hodaka's more adventurous oeuvre. In fact, years before, Tôshi had protected his brother from their father's condemnation of abstraction by maintaining Hodaka's "secret" — that he was designing abstract prints in the mid-1940s. Tôshi once said that it was Hodaka's modernist works that inspired his own abstract oils starting around 1949 and prints beginning at least by 1952.

Tôshi, working in the shadow of his demanding father, adopted Hiroshi's naturalistic drawing and compositional style. However, he sometimes selected subjects that his father did not embrace, such as views of the sea and wildlife. Soon after his Hiroshi's death, Tôshi's rebellion fully emerged when he began making abstract prints in the sôsaku hanga manner without the collaboration of the Yoshida workshop. Even so, he continued to make representational art throughout his career.

|

| Yoshida Tôshi: Raichô ("Thunderbird" or grouse: 雷鳥), 1930 Woodcut, unlimited edition, pencil signature, image: 248 x 356 mm |

One of Tôshi's early prints (his fourth known print design) is titled Raichô ("Thunderbird" or grouse: 雷鳥), a woodcut from 1930. He cut some of the blocks, but was not yet skilled enough to carve the most detailed parts. There was a long tradition of animal studies in Japanese painting and prints, classified as kachôga (flower and bird pictures: 花鳥画). The young Tôshi thereby associated himself with generations of those who came before while intentionally selecting a thematic realm that his father did not pursue. Thus, a measure of independence was gained while avoiding conflict with Hiroshi over subject matter. The grouse is called a "rock ptarmigan," a game bird of medium size. It is also known as a "snow grouse." Tôshi, still not yet twenty years of age (by Western count), demonstrates here a perceptive and detailed observation of nature.

Tôshi's oeuvre may be divided into five phases: (1) Early animal prints from 1925-1930 (see immediately above); (2) landscapes and genre scenes in keeping with his father's subject matter from 1939 (see immediately below); (3) Landscapes and genre scenes produced during the Pacific War; (4) post-war works including oil paintings, drawings, and prints both in naturalistic and abstract styles and landscapes; and (5) oil paintings, drawings, and prints on African themes. The chronicler of the Yoshida family, Eugene Skibbe, once wrote that, "At the center of Tôshi's aesthetic is a vision into the heart of things in which he sees, not fragmentation and conflict, but unity, order, and harmony. His works often contain both rational clarity (immediacy) and mystical repose. This vision guided him throughout his career, finding expression in surprising new ways in the African period (see Skibbe, Andon ref. below).

|

| Yoshida Tôshi: Shinjuku (新宿), 1938 Series: Yoru no Tokyo(Tokyo at night: 夜の東京) Woodcut, unlimited edition, pencil signature, image: 238 x 170 mm |

The view shown above was published in 1938. Shinjuku (新宿) is a special ward in Tokyo that today serves as a major shopping, entertainment, and administrative center around Shinjuku Station, the world's busiest railway station. In the early Edo period (1603-1868), it was a temporary resting place for travelers, hence the meaning of its name, "New Inn." Shinjuku was developed after the Great Kantô earthquake of 1923. By the early 1930s, the ward was a busy area with department stores, movie theaters, and cafés. The area was destroyed during the Pacific War, but was gradually rebuilt. Tôshi's scene documents the atmosphere of the pre-war site, its many shops identified by lanterns whose warm yellow glow illuminates the street. All the pedestrians are in traditional Japanese dress except for the figure on the far right, who wears a Western hat and coat.

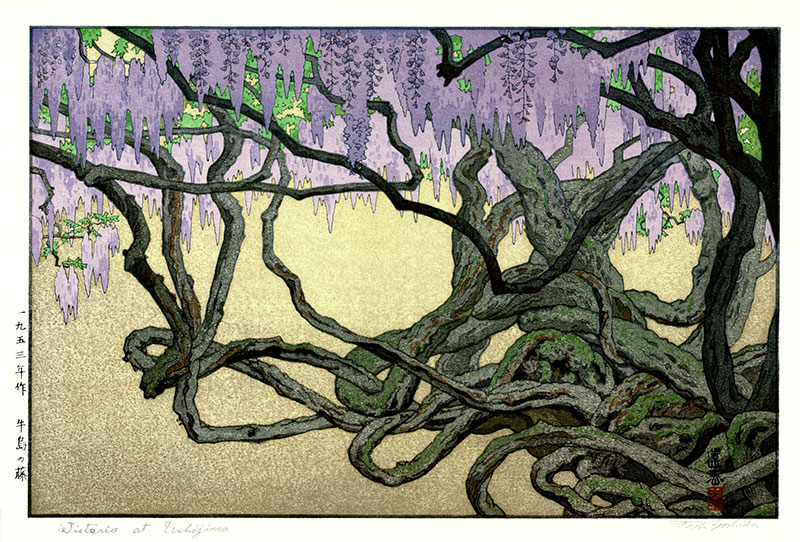

After the Pacific War,, Tôshi continued to design prints more or less following his father's aesthetic. The example shown below, from 1953, is titled Ushijima no fuji (Wisteria at Ushijima: 牛島の藤). The close focus upon the twining vines and intensely colored pendulous flowers make this one of Tôshi's more memorable nature studies. The gold-colored background evokes traditional Japanese screen paintings done on gold-leaf.

|

| Yoshida Tôshi: Ushijima no fuji (Wisteria at Ushijima: 牛島の藤), 1953 Woodcut, unlimited edition, pencil signature, image: 243 x 371 mm |

Starting around 1949, Tôshi began to explore abstraction, prompted in part by the work of his brother Hodaka, but also by his awareness of non-objective art in the West. At first he painted a few oils on canvas. These included, in 1949, "Three Women" and "Whirlpool," each measuring 640 x 530 mm (see second Skibbe ref. below). In 1952, two years after Hiroshi's death, Tôshi embarked upon a long period of producing abstract prints while also working on naturalistic landscapes, nature views, and scenes from his travels abroad. By one count, his abstract prints number 289 works from 1952 to 1975 (most were made from 1954 to 1965). Two examples are shown below.

The image on the left is titled "Polarization" from 1962, which was issued in an edition of 100. It is one of the more dramatic abstract designs from Tôshi, with anthropomorphic forms inscribed with hieroglyphs of his own invention, with possible influences from Mesoamerican glyphs, Chinese bronzes, and Native American patterns. They also recall some of the prints made by his brother Hodaka, which were inspired by the Mayan art that the two of them saw while visiting Mexico in 1955.

The woodcut below right is titled "Creation" from 1968. Here, five variants of multi-color forms float against a quietly textured background. The shapes — crescents with extended, complex stems or tails — vaguely suggest, whether intentional or not, letters in the Arabic alphabet. Perhaps, instead, there is a connection to astral imagery, a sort of personal cosmology expressed in forms and colors. Regardless, the delicacy and refinement of the shapes and chromatic gradations represented another realm of exploration for Tôshi in his abstract oeuvre.

|

|

| Yoshida Tôshi: Polarization, 1962 Woodcut, edition: 100; pencil signature, image Paper: 405 x 282 mm |

Yoshida Tôshi: Creation, 1968 Woodcut, edition: 200; pencil signature, image Paper: 410 x 277 mm |

Several of Tôshi's finest naturalistic works can be found among his 29 woodcuts depicting African scenes, as well as about fifteen oil paintings and a large number of sketches. He had traveled to Africa in 1972, and the experience inspired him to capture in visual media the forces of nature. In addition to the nearly 30 woodcuts, he also painted more than a dozen oils.

_220w.jpg) Moreover, Tôshi devoted twelve years (1982 to 1993) to writing and illustrating a series of children's books about animal life in Africa called Dôbutsu ehon shiriizu ― Afurika (Picture-book of animal life in Africa: 動物絵本シリーズ―アフリカ). The first volume, a set of five books, is titled Hajimete no kari (The First Time [First Hunt]: はじめてのかり); see book cover at right. Skibbe offered the following description: "The stories Tôshi tells are based on careful observation as well as scientific data.... The first set of five books ... tells the story of three immature lions ... tired of playing within sight of the pride, venture out on their own to 'really' hunt. From that premise the reader is taken on a walking tour of the various animals ... rhino, water buffalo, cattle, egrets, zebra, impalas, cheetahs, gnu, vultures, hyenas, a leopard, and a porcupine. At each encounter the young lions are either rebuffed or prove too timid to give chase." (See second Skibbe ref. below.) The book series was intended to number twenty volumes, but it ended three shy at seventeen volumes. These illustrated storybooks were critically acclaimed both in Japan and Europe, winning a prize at the Children's Book Fair, Bologna, in 1984; the Nippon prize from the Yomiuri newspaper in 1985; an art prize from the Sankei newspaper, also in 1985; and a culture prize in Evian, France.

Moreover, Tôshi devoted twelve years (1982 to 1993) to writing and illustrating a series of children's books about animal life in Africa called Dôbutsu ehon shiriizu ― Afurika (Picture-book of animal life in Africa: 動物絵本シリーズ―アフリカ). The first volume, a set of five books, is titled Hajimete no kari (The First Time [First Hunt]: はじめてのかり); see book cover at right. Skibbe offered the following description: "The stories Tôshi tells are based on careful observation as well as scientific data.... The first set of five books ... tells the story of three immature lions ... tired of playing within sight of the pride, venture out on their own to 'really' hunt. From that premise the reader is taken on a walking tour of the various animals ... rhino, water buffalo, cattle, egrets, zebra, impalas, cheetahs, gnu, vultures, hyenas, a leopard, and a porcupine. At each encounter the young lions are either rebuffed or prove too timid to give chase." (See second Skibbe ref. below.) The book series was intended to number twenty volumes, but it ended three shy at seventeen volumes. These illustrated storybooks were critically acclaimed both in Japan and Europe, winning a prize at the Children's Book Fair, Bologna, in 1984; the Nippon prize from the Yomiuri newspaper in 1985; an art prize from the Sankei newspaper, also in 1985; and a culture prize in Evian, France.

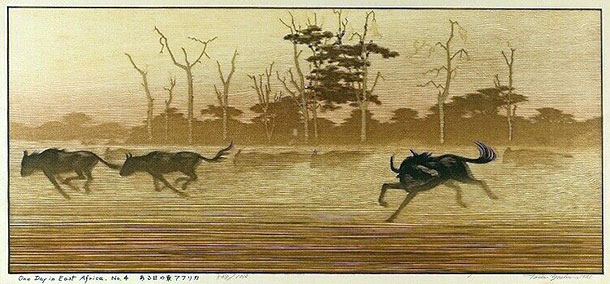

An example from Tôshi's excellent series of ten woodcuts titled Aru hi no Higashi Afurika ("One day in East Africa": ある日の東アフリカ) is shown below. Wildebeest are in full stride as they race across the African savanna. The design is one of several in which Tôshi captured swift animal movement using brilliant carving and printing techniques. Some of the lines create a moiré effect on either side of the wildebeest in the right foreground, achieved by printing two separate blocks carved with parallel curving lines that overlap. The warm tan-yellow hue dominating the print suggests the heat on the savanna.

|

| Yoshida Tôshi: Aru hi no Higashi Afurika (One day in East Africa no. 4: ある日の東アフリカ no. 4), 1981 Woodcut, edition, 1,000; pencil signature, image: 270 x 600 mm |

Tôshi's final work is shown at the top of this page, a view of two red-crowned cranes engaged in a mating dance. Carved and printed in 1994, the woodcut measures 330 x 445 mm. Tôshi's depiction of the elegant birds amidst falling snow captures an elemental moment in nature, evoking the cycles of life and regeneration.

In 1991-1992, Tôshi supervised the construction of a small family museum in Atami, Shizuoka Prefecture, which became a showcase for the diverse talent among the many artists in the Yoshida family. Tôshi's works are in numerous private and public collections, including the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia; Art Institute of Chicago; Asian Art Museum, San Francisco; British Museum, London; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Cincinnati Art Museum; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Harvard Art Museums; Honolulu Museum of Art, Hawai'i; Krakow National Museum, Poland; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Museum of Art, Atami, Japan; Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian, Washington, DC; National Museum of Australia, Canberra; National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; National Museums of Scotland; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Portland Art Museum, Oregon; Paris National Library; Seattle Museum of Art; and Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio.

Note about editions: Nearly always, lifetime signatures are pencil-signed in English by Tôshi, whereas posthumous signatures are stamped facsimiles. However, very late in his career, when illness and weakness in his writing hand prevented him from signing, Tôshi supervised the studio printing and, on impressions he approved, used a stamped signature accompanied by an embossed seal. The same applies for both numbered and unlimited editions. The following examples are small and thus not entirely effective in demonstrating differences, but perhaps what can be seen here is that the pencil signature is smooth throughout the strokes. The two stamped signatures, however, appear somewhat broken or erratic in their strokes as if uneven pressure had been applied (this seems to be an artifact of the facsimile stamps).

| Lifetime pencil signature | Late lifetime stamped signature with embossed artist seal at right |

Posthumous stamped signature |

This is not the place for a discussion of market values typically associated with pencil-signed versus posthumous printings, but, clearly, greater value is assigned by collectors and museums to lifetime impressions, and to pencil-signed impressions over lifetime stamp-signed & embossed-seal impressions.

![]()

Some posthumous impressions included Japanese characters on the reverse side of the print that indicate a late printing (atozuri, 後摺) by the printer (suri, 摺) Komatsu Heihachi (小松平八 died 2018), a master craftsman in the Yoshida Studio located in Setagaya-ku, Tokyo (see image at left). Komatsu can be seen in a series of photographs demonstrating the process of printing a design by Yoshida Hiroshi (吉田博), Toshi's father, on pages 175-176 in the Ogura reference cited below.

Some posthumous impressions included Japanese characters on the reverse side of the print that indicate a late printing (atozuri, 後摺) by the printer (suri, 摺) Komatsu Heihachi (小松平八 died 2018), a master craftsman in the Yoshida Studio located in Setagaya-ku, Tokyo (see image at left). Komatsu can be seen in a series of photographs demonstrating the process of printing a design by Yoshida Hiroshi (吉田博), Toshi's father, on pages 175-176 in the Ogura reference cited below.

After Komatsu grew too old to continue printing for the Yoshida family, Numabe Shinkichi (沼辺伸吉 born 1952), who had worked alongside Komatsu, became the primary printer for the studio, which is now run by Tsukasa Yoshida (吉田司 born 1949), son of Toshi, and grandson of Hiroshi. As of early 2022, the more recent posthumous reprintings from the original blocks of certain designs by Toshi are still being made by Numabe. In July 2015, David Bull (born 1951, woodblock carver and printer, and owner of the Mokuhan printmaking shop), wrote the following in a blog: "The blocks for Toshi-san's prints are all held by his son Tsukasa. In recent years, they have been re-printed one by one by their [Yoshida Studio] customary printer Shinkichi Numabe (who also does much work for Dave's Mokuhankan venture). The Mokuhankan shop has a selection of these reprints [around 70 designs], but others are also available on request." All of Toshi's woodcuts printed by Numabe should have his name stamped on the reverse side following the characters for atozuri ("late printing": 後摺) and suri ("printer": 摺); see image at right. Moreover, the titles and signatures on the front in the margins will be stamped.

A video of Numabe working on a reproduction of Hokusai's Great Wave can be viewed at Numabe Shinkichi video. © 2020-2022 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Brown, Kendall: "Shin-Hanga: Yoshida Tôshi — The Nature of Tranquility," in: Allen, Laura, et al.: A Japanese Legacy: Four Generations of Yoshida Family Artists. Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2002, pp. 71-107.

- Catalogue of Collections [Modern Prints]: The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (Tokyo kokuritsu kindai bijutsukan shozô-hin mokuroku, 東京国立近代美術館所蔵品目録). 1993, pp. 261-262, nos. 2518-2530.

- Ogura, Tadao (Ed.): The Complete Woodblock Prints of Yoshida Hiroshi. Tokyo: Abe Publishing Co., 1987, pp. 175-176.

- Skibbe, Eugene: "Yoshida Tôshi, 1911-1995: Diversity, Change, and Continuity in the Yoshida Art Tradition," in: Andon 53, 1996, pp. 8-14.

- Skibbe, Eugene: Yoshida Toshi: Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape Publications, 1996.

- Smith, Lawrence: Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989. London: British Museum Press, 1994, p. 39, and plate 51.

- Smith, Lawrence: The Japanese Print Since 1900: Old dreams and new visions. London: British Museum Press, 1983, pp. 90-91, 94-94, 102, 106, nos. 83-86.

- Tôshi Yoshida, Rei Yuki: Japanese Print-Making. A Handbook of Traditional & Modern Techniques. Rutland, VT: Tuttle, 1966.

Viewing Japanese Prints |