MAEDA Masao (前田政雄)

|

Maeda Masao (前田政雄), who was born in Hakodate City, Hokkaido, wanted to be an artist from an early age. His aspirations were heightened in 1923 when he met Hiratsuka Un'ichi at an exhibition in Hakodate. Maeda moved to Tokyo in 1925 where he attended the Kawabata Ga-Gakkô (founded in 1909), a private painting school headed by the Shijô-style (naturalistic) artist Kawabata Gyokusho (1842-1913). He eventually became dissatisfied with the instruction there and went on to study yôga (Western-style painting: 洋画) with the eminent and influential painter Umehara Ryûzaburô (梅原龍三郎 1888-1986), who also happened to know Hiratsuka. Maeda lived near Hiratsuka and visited often, providing him with opportunities to observe Hiratsuka carve blocks and make prints. Maeda picked up some printmaking techniques in this way and was soon designing and making his own hanga (woodcuts or block prints: 版画).

Maeda Masao (前田政雄), who was born in Hakodate City, Hokkaido, wanted to be an artist from an early age. His aspirations were heightened in 1923 when he met Hiratsuka Un'ichi at an exhibition in Hakodate. Maeda moved to Tokyo in 1925 where he attended the Kawabata Ga-Gakkô (founded in 1909), a private painting school headed by the Shijô-style (naturalistic) artist Kawabata Gyokusho (1842-1913). He eventually became dissatisfied with the instruction there and went on to study yôga (Western-style painting: 洋画) with the eminent and influential painter Umehara Ryûzaburô (梅原龍三郎 1888-1986), who also happened to know Hiratsuka. Maeda lived near Hiratsuka and visited often, providing him with opportunities to observe Hiratsuka carve blocks and make prints. Maeda picked up some printmaking techniques in this way and was soon designing and making his own hanga (woodcuts or block prints: 版画).

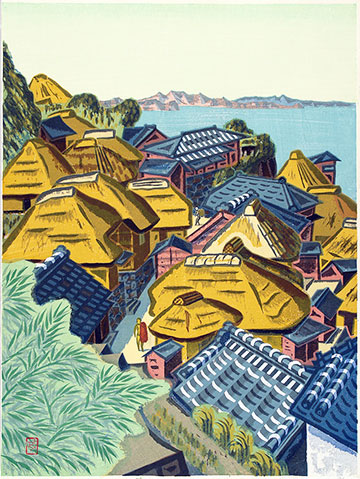

Early on, line-work was paramount, but as Maeda's style evolved, more massive forms, frequently without keyblock outlines, appeared along with denser colors. Often, he also used cardboard blocks for shading. Landscapes would prove to be Maeda's favored subject, although he did design occasional figure studies and still lifes. The image on the right from 1939 (edition of 30) depicts a fishing village situated against a hillside as seen from the top of a steep road on a sunny day. The large format design (image 603 x 450 mm) uses thick contour lines for the shapes of the houses whose roofs are colored with saturated yellows and blues.

Maeda assisted Hiratsuka with the administration of the print division of the Kokugakai (National Painting Association: 国画会), including organizing exhibitions of modern hanga. By 1927 Maeda was exhibiting oil paintings at the Kokugakai, adding hanga in the 1930s, and then exclusively hanga in the 1940s. He also became affiliated with Hiratsuka's circle of artists, called the Yoyogi-ha (Yoyogi clique: 代々木派), a group of print artists who gathered at Hiratsuka's house in the Yoyogi district of Tokyo in the 1930s. Although Maeda seemed a typical sôsaku hanga artist by taking an individualized approach to printmaking, his training in oils, Shijô-style painting, and yôga led to some elements of Nihonga (Japanese native-manner painting: 日本画) and Western-influenced painting appearing in his hanga. He specifically cited Umehara as an influence, and of course, Hiratsuka, as well as other Japanese artists such as Maekawa Senpan and Onchi Kôshirô. There might have been as well some "cross-fertilization" between Maeda and Azechi Umetarô, whose landscapes sometimes had similar styles and printing techniques (they both engaged with Hiratsuka at the same time). In the West, the great French painters Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Henri Matisse (1869-1954), and Georges Braque (1882-1963) captured Maeda's imagination, although direct influence is often difficult to identify. However, the bright color palette of the fishing village scene shown above does hint at Matisse's sun-bathed Mediterranean views. The tree at the lower left also paraphrases the French master.

Maeda's other participatory activities included contributing to dôjin-zasshi (coterie magazines: 同人雑誌): one design for volume 11 of HANGA (版画) in 1930; one for Kitsutsuki (woodpecker: きつつき) in 1930; and one for Kitsutsuki hangashû (Woodpecker print collection: つつき版集画集) in 1942-43. Maeda also provided designs for four of Onchi Kôshirô's group-project Ichimokushû (First Thursday Collection: 一木集), specifically, in volumes 3-6 (1947-50). He also contributed one design to the series Shin Nihon hyakkei (One hundred new views of Japan: 新日本百景 1938-41) in 1939; one to Tokyo kaiko zue (Scenes of lost Tokyo, or Recollections of scenes in Tokyo: 東京回顧圖會), a portfolio from 1945 of 15 prints by nine artists who were members of the Nihon Hanga Kyôkai (Japan Print Association: 日本洋画協会); and one to Nihon minzoku zufu (Folk customs of Japan, illustrated: 日本民族図譜, a portfolio of 12 woodblock print by ten artists in 1946.

|

| Meada Masao: Untitled view, 1928, woodcut (140 x 200 mm) |

The influence of Hiratsuka was enormous for Maeda, especially in the manner of carving his designs and printing from the blocks, as well as rendering the light-and-dark values. A fairly early work from 1928 demonstrating this influence is shown above. The untitled scene depicts a raised road winding its way past houses and highly stylized trees. The white outline method was one that Hiratsuka had used earlier. The view is both naturalistic and a bit fanciful in its rendering of the forms.

|

| Maeda Masao: Fukagawa-kiba (Fukagawa lumberyard), 1929, woodcut (image: 135 x 192 mm) |

The following year, Maeda produced one of his early color woodcuts, a view of the Fukagawa lumberyard (see above). Fukagawa is a site that dates back to the aftermath of the Edo-Meireki fire of 1657 when the shogunate authorized establishing lumber production on swamp-land east of the Sumida River, mainly in Fukagawa, where they also constructed a maze of canals, bridges, and landings. The area remained a lumberyard until the early 1970s, when it was relocated to Shin-kiba (New Lumberyard: 新木場). The old yard was then turned into Kiba Kôen (Kiba Park: 木場公園). The Fukagawa yard had a long history in woodblock prints. Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), for example, designed a print for his Meisho Edo hyakkei (One hundred famous views of Edo: 名所江戸百景) in 1856. A number of sôsaku hanga artists portrayed these lumber yards as well, including Un'ichi Hiratsuka (1895-1997), Kishio Koizumi 1893-1945), and Maekawa Senpan (1888-1960). The color palette used by Maeda is unusual, with a strong purple and middle blue offset by a hot yellow and dark red. The artist's seal in the lower left corner reads "Masa" (政).

|

| Maeda Masao: Kokuhô Akamon (National treasure, Red gate: 国宝赤門), 1945, woodcut (image: 186 x 362 mm) From the series Tokyo kaiko zue (Scenes of lost Tokyo: 東京回顧圖會); published by Fugaku Shuppan |

The image above represents Maeda's contribution to the aforementioned series Tokyo kaiko zue in 1945. The Akamon (Red gate: 赤門) was part of Tokyo's Imperial University (Tokyo teikoku daigaku: 東京帝國大學), now called the University of Tokyo (Tokyo daigaku: 東京大学) and a designated kokuhô (national treasure: 国宝). The Akamon is a historical gate in the Bunkyô ward of Tokyo that, in 1903, became part of the entrance to the university's Hongo campus. It is one of two remaining gates in the city that were once part of Edo-period daimyô (military lord: 大名) mansions (the other one is Kuromon, located in the Tokyo National Museum). Akamon was built in 1827 within the Kaga domain residence of the Maeda clan, one of the period's most powerful samurai families. The purpose of the gate was to welcome Lady Yasu-hime (1813-1868), the twenty-first daughter of the shôgun Tokugawa Ienari, as a bride for Maeda Nariyasu (1811-1884). At the end of the Meiji period (1868-1912), the gate was moved to its current location, 15 meters west of where it first stood. Maeda's depiction is a straightforward rendering of the gate flanked by two guard posts and pedestrians walking through the central portal and the two open doors on either side.

|

| Maeda Masao: Komagatake (Mount Koma-ga-take: 駒ヶ岳), 1950, woodcut (image: 174 x 174 mm) From the portfolio Ichimokushû VI (First Thursday Collection VI: 一木集); produced by Ichimokukai |

Maeda's final contribution to the Ichimokushû (First Thursday Collection: 一木集) was included in the last (1950) portfolio produced by the Ichimokukai (First Thursday Society: 一木会) led by Onchi Kôshirô. For this project, Maeda depicted the active Komagatake volcano in Hokkaidô (北海道). The small, square woodcut conveys the rugged mountain terrain at 1,131 meters (3,711 ft.), rendered with simple forms and shading, and extensive texture on the mountain and in the sky and clouds. The sharp diagonal peak of the mountain has a rather foreboding shape, as two plumes of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and sulfur gases (and ash) rise up from the middle right. The foreground in dark brown is punctuated by lively thick black strokes representing tree branches. The artist's Masa (政) seal is at the lower right.

|

| Maeda Masao: Tôfukuji tobi-ishi (Stepping stones at Tôfuku Temple: 東福寺飛び石) Woodcut, 1970, edition of 60 (paper: 498 x 377 mm) |

An example from late in Maeda's career is shown above — a view of stepping stones and thick green moss in a garden at the Tôfukuji (Tôfuku Temple: 東福寺) in Kyoto. Tôfukuji is a principal Zen temple in southeastern Kyoto. It was founded in 1236 by the imperial chancellor Kujô Michiie (1193-1252) at the request of the powerful Fujiwara clan. The temple was destroyed by fire but rebuilt according to original plans in the 15th century. Currently, the complex includes 24 sub-temples, although in the past the number has been as high as 53. The temple combines the names of two great temples in Nara that were also associated with the Fujiwara — the Todaiji and Kofukuji. The main gate has been designated a kokuhô (national treasure: 国宝) and, today, the site is particularly famous for its spectacular autumn colors, especially when seen from the Tsûten-kyō Bridge. There are a number of gardens in the various precincts of Tôfukuji. The moss garden is considered emblematic of the renewal of Japanese gardening principles in the 20th Century. Maeda's choice of viewpoint in his woodcut is surprising, as it leans toward abstraction, with pattern rather than mere representation as its focus.

Public collections with works by Maeda Masao include the Art Institute of Chicago; British Museum, London; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Chiba City Art Museum; Harvard Art Museum; Honolulu Museum of Art; Museum of Fine Art, Boston; Portland Art Museum; and Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Chiba-shi Bijutsukan (Chiba City Art Museum: 千葉市美術館): Nihon no hanga 1931-1940 (Japanese prints 1931-1940), Vol. IV, 2004, no. 287-3; and Nihon no hanga 1941-1950, Vol. V, 2008, nos. 39, 47, and 62-1.

- Jenkins, D.: Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century. Portland Art Museum, 1983, p. 114, no. 95.

- Merritt, Helen: Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990, pp. 250-251.

- Riccar Art Museum: Ichimokukai ten: Onchi Kôshirô to sono shûhen (First Thursday Society exhibition: Onchi Kôshirô and his cricle). Tokyo: 1979, nos. IV-20, V-13, and VI-20.

- Shiga, Hidetaka: Ki hanga no nukumori Kobayashi Kiyochika kara Munakata Shikô made (The warmth of woodblock prints: From Kobayashi Kiyochika to Munakata Shikô: 木版画のぬくもり小林清親から棟方志功まで). Tokyo: Fuchûshi Bijutsukan (Fuchû Art Museum: 府中市美術館), 2005, pp. 65 and 92, nos. 127-129.

- Smith, Lawrence: Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989. British Museum, 1994, p. 29 and color plate 22.

- Statler, Oliver: Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn. Rutland & Tokyo: Tuttle, 1956, pp. 131-133, and 199-200, nos. 77-78.

- Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art — Catalogue of collections: prints (Tokyo Kokuritsu Kindai Bijutsukan — Shozô-in mokuroku (東京国立近代美術館 • 所蔵品目録). Tokyo: 1993, pp. 241-242, nos. 2315-2318.

Viewing Japanese Prints |