Mu Tamagawa

|

Mu Tamagawa ("Six Jewel Rivers," also "Six Crystal Rivers": 六玉川 or 六玉河) was a popular subject in ukiyo-e prints. It represented rivers in six provinces, each associated with classical poems:

Mu Tamagawa ("Six Jewel Rivers," also "Six Crystal Rivers": 六玉川 or 六玉河) was a popular subject in ukiyo-e prints. It represented rivers in six provinces, each associated with classical poems:

- Ide (Hagi) no Tamagawa in Yamashiro

- Mishima (Tôi or Kinuta) no Tamagawa in Settsu

- Noji no Tamagawa in Omi

- Kôya no Tamagawa in Kii

- Chôfu no Tamagawa in Musashi

- Noda (Chidori) no Tamagawa in Mutsu.

The subject of Mu Tamagawa might have developed as a response to the building of the great aqueduct to draw water from the Tamagawa in Musashi, began in 1652 and completed in 1654, while the iconography of the six Tamagawa was possibly the result of creating decorations for Edo Castle to commemorate the project. It appears that the Mu Tamagawa were not popular subjects for painters, as only 2 or 3 paintings survive (one by Sumiyoshi Gukei, 1631-1706; a handscroll by Sakai Oho, 1808-41; and possibly some no longer extant wall paintings at Edo Castle by Kanô Tanyû, 1602-74).

In contrast, the six rivers were quite popular among Edo printmakers, as in the works of luminaries of the ukiyo-e school such as Suzuki Harunobu, Kubo Shunman (1757-1820), Kitagawa Utamaro, Katsushika Hokusai, and Utagawa Hiroshige I. Their works included not only treatments of the subject as meisho-e ("pictures of famous places"), but also as allusion pictures (mitate-e) in which beautiful women (bijin) or courtesans were situated in a context related to the Mu Tamagawa. The theme also appeared in works by performers of dance and song (for example, in the nagauta or "long-song" style).

The context of meisho-e could be explained further. Meisho, literally "place with a name," is a term often translated as "famous places" or "celebrated sites." The earliest known meisho-e were probably painted as a sub-genre of early yamato-e ("Japanese painting") and were first linked as well to shiki-e ("pictures of the four seasons") and tsukinami-e ("pictures of the twelve months"). Commonly found in the titles of ukiyo-e prints and series, the connotation implies a place with literary and historical attributes. There were standardized poetic associations as well, often more significant than the actual geographic or topological characteristics of the place. Seasonal associations were also important, and when linked to specific seasonal poems became the conventional time of year for depicting a famous site, even when that season would not present the site at its most beautiful.

The meisho of traditional views were most frequently linked to the old capitals of Nara and Kyoto, while the popular culture of Edo used the term for more immediate sights and locales (note especially Hiroshige's series Meisho Edo hyakkei or "One Hundred Famous Views of Edo"). By the Edo period (1603-1868) a distinction may have developed between meisho-e and the more traditionally bound shiki-e and tsukinami-e in which meisho-e tended to emphasize a public and specifically site-oriented expression (sometimes even political in nature), compared to the more private function of traditional pictures.

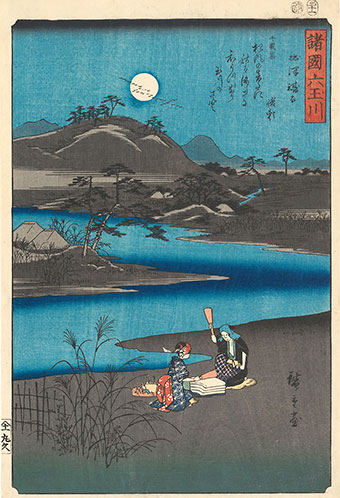

In a common ukiyo-e treatment of this theme, two women would be portrayed cleaning and thickening layers of cloth with heavy wooden mallets as they sit by the Kinuta River below a full moon silhouetting flying geese. In the example shown at the top of this page, Hiroshige shows us a famous and specific place, with a convincingly real physicality, but his atmospheric design also alludes to the poetic possibilities associated with such a meisho. His design is titled Settsu kinuta no Tamagawa (Fulling block, Jewel River, Settsu: 摂津擣衣之玉川) with the series title in the red cartouche at the top right, Shokoku mu Tamagawa ("Six jewel rivers in the Provinces: 諸国六玉川). It was published in 1857 by Marukyû (丸久 Maru-ya Kyûshirô), whose seal is in the lower left margin. The theme and mood is amplified by the poem usually linked to the Kinuta theme, which is here inscribed at the upper right of the image. It is by Minamoto no Toshiyori (c. 1055 - 1129), poem 339, from the anthology Senzaishû ("Collection of poems of a thousand years," 1187-88):

Matsukaze no / oto dani aki wa / sabishiki ni / koromo utsu nari / Tamagawa no sato

The autumn wind over the pines / sounds forlorn / in the loneliness / the sound of fulling cloth / by the Jewel River

Besides being the name of a river, kinuta also meant "fulling block," which was associated with a kind of attractive sadness and a reminder of the passing of the seasons, as well as with the loneliness of a woman separated from, or abandoned by, a husband or lover. The repetitive sound of the beating of the cloth echoed the monotony of separation and thus a woman's melancholic emotional state. This association had ancient antecedents, such as in verses by the Chinese T'ang poet Po Chü-i (772-846), who was well-known to educated Japanese; in the early eleventh century masterpiece Genji monogatari ("Tale of Genji") by Murasaki Shikibû (dates uncertain); and in Japanese verse anthologies such as the Shinkokin wakashû ("New Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems," 1205). Hiroshige designed at least eight other prints on the Kinuta subject in addition to this evocative version.

|

| Utagawa Hiroshige I (landscape), c. 1835-36 |

Hiroshige had used a very similar approach to the Kinuta subject about two decades earlier, as shown immediately above in the horizontal ôban format. It is also titled Settsu kinuta no Tamagawa (Fulling Block, Jewel River, Settsu Province: 摂津擣衣之玉川) with the series title in the margin cartouche, Shokoku mu Tamagawa ("Six jewel rivers in the Provinces: 諸国六玉河), using a different last character than in the later print design. This horizontal format version was published by Tsutaya Jûsaburô (蔦屋重三郎) about two decades earlier than our first example (circa 1835-36).

Although the elements of the composition are similar to the later vertical design and it is a good scenic treatment of the Kinuta theme, the horizontal version seems to lack some of the expressive poetic power of the later example. The receding space is shallower in the horizontal format (later impressions of this version lack the background hills, creating an even shallower depth of field), while the figures of the women (plus the additional figure of the young boy grasping his mother's arm) are featured more prominently as they are closer to the frontal plane of the pictorial space. This creates the effect of a more action-specific or prosaic interpretation of the conventional theme, as though the task set before the women were more important than the famous place itself. In the later vertical format design the two women are shown at a greater distance from the viewer and are more assimilated into the vista of a poetically evocative landscape — overall, there is more of an iconographic aspect to the later vertical composition.

Although the elements of the composition are similar to the later vertical design and it is a good scenic treatment of the Kinuta theme, the horizontal version seems to lack some of the expressive poetic power of the later example. The receding space is shallower in the horizontal format (later impressions of this version lack the background hills, creating an even shallower depth of field), while the figures of the women (plus the additional figure of the young boy grasping his mother's arm) are featured more prominently as they are closer to the frontal plane of the pictorial space. This creates the effect of a more action-specific or prosaic interpretation of the conventional theme, as though the task set before the women were more important than the famous place itself. In the later vertical format design the two women are shown at a greater distance from the viewer and are more assimilated into the vista of a poetically evocative landscape — overall, there is more of an iconographic aspect to the later vertical composition.

Even so, the horizontal composition was adapted by an unidentified artist who copied it in a much smaller size, reducing the original ôban (large print: 大判 about 250 x 380 mm) to a koban (small print: 小判 about 122 x 163 mm). As a result, there is a compression in the aspect ratio of the composition, as if the two vertical sides were squeezed toward the center. Given that the publisher seal in the lower right margin reads "Honsei" (本清 Honya Seishichi, 本や清七), the work must have been issued in Osaka. The purpose of this adaptation was not to achieve the poetic expressiveness of Hiroshige's 1857 vertical ôban version. Rather, it was simply to provide an inexpensive, locally (Osaka) distributed image of a landscape design by the great Edo master. Such copies were common enough in the region, where the landscape craze seems never to have taken hold after the late eighteenth century, when woodblock-printed landscapes and cityscapes in illustrated guide books called meisho-ki (名所記) were popular. © 2000-2019 by John Fiorillo

For more discussion related to Hiroshige, see Hiroshige I, Meiji Recuts, Mutamagawa, and Woodgrain

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Murase, M.: "The Evolution of Meisho-e and the Case of Mu Tamagawa," in: Orientations, 1995; 1:94-100.

- Murase, M.: Bridge of Dreams: The Mary Griggs Burke Collection of Japanese Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000, pp. 319-331.

Viewing Japanese Prints |