Keisai Eisen (渓齋英泉)

|

Keisai Eisen (渓齋英泉) — painter, woodblock print designer, and book illustrator — was born in Edo into the Ikeda family. He was the son of the samurai Ikeda Masahei Shigeharu, a Kanô-school painter and talented calligrapher. Eisen, whose family and given name was Ikeda Yoshinobu (池田義信) and common name Zenjirô (善次郎), was known by an array of art names: Keisai (渓齋), Kokushunrô (國春楼); Koizumi (小泉), Ippitsuan Kakô (一筆庵可候), Fusen Ichiin (楓川市隠), Mumei'Io (无名翁), Insai Hakusui (淫齋白水), Inransai (淫乱齋). He might also have used the names Hokutei (北亭) and Hokkatei (北花亭).

Keisai Eisen (渓齋英泉) — painter, woodblock print designer, and book illustrator — was born in Edo into the Ikeda family. He was the son of the samurai Ikeda Masahei Shigeharu, a Kanô-school painter and talented calligrapher. Eisen, whose family and given name was Ikeda Yoshinobu (池田義信) and common name Zenjirô (善次郎), was known by an array of art names: Keisai (渓齋), Kokushunrô (國春楼); Koizumi (小泉), Ippitsuan Kakô (一筆庵可候), Fusen Ichiin (楓川市隠), Mumei'Io (无名翁), Insai Hakusui (淫齋白水), Inransai (淫乱齋). He might also have used the names Hokutei (北亭) and Hokkatei (北花亭).

Eisen was tutored in the art of kabuki playwriting by Shinoda Kinji (篠田金治 1768 - 7/1819; later name Namiki Gôhei II, 並木五瓶 from 11/1818), who wrote criticism for yakusha hyôbanki (actor critiques: 役者評判記) and whose best known contribution was the dance classic Yasuna (保名) premiering in 3/1818. Eisen used the pen name Chiyoda Saishi [or Saiichi] (千代田才市); however, nothing of lasting significance seems to have come from his playwriting endeavors. In the visual arts, Eisen studied with a minor painter named Kanô Hakkeisai, from whom he took the name Keisai, and later he had some not entirely confirmed connection with Kikugawa Eizan, either as a pupil or lodger in the Kikugawa household where he is said to have studied painting with Eizan's father, Eiji, and ukiyo-e design with Eizan. Scholars also mention the influence of Katsushika Hokusai upon the young Eisen, as well as that of Yanagawa Shigenobu I (1787-1832).

Eisen was one of several writers and artists who edited and expanded upon the Ukiyo-e ruikô (History of prints of the floating world: 浮世絵類考), the most informative 18th-19th century source of information on the lives of ukiyo-e artists. Eisen's version (circa 1833) was called the Zoku ukiyo-e ruikô (Supplement to the history of prints of the floating world: 続浮世絵類考), known also as the Mumei'ô zuihitsu ("Essays by a nameless old man": 无名翁随筆). He described himself as a hard-drinking, rather dissolute artist. In the 1830s, he ran a brothel called the Wakatakeya in Nezu, although it soon burnt down. He also had a business selling face powder, and tried his hand at writing kabuki plays and popular fiction (sharebon 洒落本, ninjôbon 人情本, yomihon 讀本, and kyôkabon 狂歌本). Nevertheless, by the 1820s Eisen established himself as a leading and prolific designer of bijinga (pictures of beautiful women: 美人画). His finest works, particularly his ôkubi-e ("large-head pictures"), are now considered masterpieces of the Bunsei period (文政時代 1818-1830). These portraits of beauties and courtesans are much admired for their pronounced elements of realism and sensuality.

Throughout this period he also produced large numbers of full-length portraits, many involving women of the Yoshiwara. The print at the top right depicts the courtesan Nagatô of the Owariya brothel (Owariya uchi Nagatô): 尾張屋内長登), one design from the series Yoshiwara hakkei (Eight views of the Yoshiwara: 吉原八景), inscribed in the black cartouche. This is one of the ever-popular mitate (見立) or analogues of the traditional eight views of Lake Biwa in Omi Province, in this case the Mii no banshô ("Evening Bell at Mii [Temple]: 三井の晩鐘), identified at the far left of the large reddish-brown cartouche. The publisher's seal of Tsutaya Kichizô appears at the lower right below a kiwame (approved: 極) censor seal and above the artist's signature, Keisei Eisen ga (渓齋英泉画). Nagatô is on public display during a promenade in the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter. It is early spring, as she walks beneath a flowering cherry tree enclosed by a bamboo fence on Yoshiwara's main street, the Naka-no-chô (Middle Street: 仲の町). Budding cherry trees were planted each year on the 25th day of the second month in preparation for the famous annual cherry blossom festival held during the third month. Many spectators would visit not only to enjoy the blossoming trees, but also to stand in the street or sit in the upper stories of teahouses to view the colorful spectacle of parading courtesans. Nagatô's name is composed of characters that suggest superiority and excellence (naga 長) at a high "ascent" (tô 登) or price. Thus, she is a high-ranking courtesan, probably an ôiran (花魁). Her robes and accessories are of the most elaborate and expensive type for the period. Six tortoise-shell hairpins jut out on either side of her coiffure, and a large obi (sash: 帯) is tied at the front in the manner of dress for courtesans. Most spectacular, of course, is the pattern of a fierce tiger standing on rocks amidst a waterfall. Such kimono were affordable by only the highest ranking courtesans (the design, fabricating, and acquisition of robes were sometimes subsidized by, or obtained as gifts from, wealthy patrons). Eisen's vision of this Yoshiwara beauty exemplifies the standards of Edo style and fashion during the 1820s-30s when ornate elaboration of deportment and dress was considered the ideal for the most accomplished women of the pleasure quarters.

|

|

| Keisei Eisen: Yo o fukasahite asane no te "Habit of staying up late and sleeping in the morning" (夜をふかして朝寝の手) Pub: Matsumura Tatsuemon, ôban, c. 1821-22 |

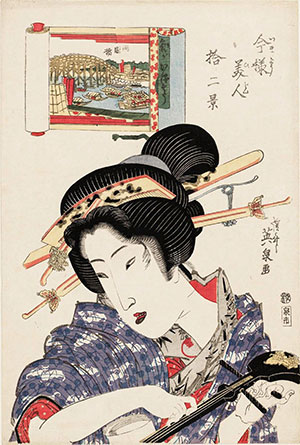

Keisei Eisen: Ki ga karusô (Cheerful-looking: 気がかるう) Series: Imayô bijin jûni kei (今様美人拾二景) "Twelve views of modern beauties" Pub: Izumiya Ichibei (Kansendô), ôban, c. 1822-23 |

The best of Eisen's bijin ôkubi-e ("large head" pictures of beauties: 美人大首絵) are among his finest works. They express an awareness of the ethos of his time when realism, albeit stylized, came to define the typology of women seen in paintings and prints. Rather than continue with drawing the idealized, graceful creatures of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Eisen (along with Utagawa Kunisada and Utagawa Kuniyoshi) turned toward a feminine iki (stylishness or spiritedness: 粋 or 粹) that was distinctly different from his predecessors' views of women. In Eisen's bijinga, there is greater angularity. The noses of his beauties are long and straight, and the faces overall are more rectangular. The double ôkubi-e shown above left is titled Yo o fukasahite asane no te (The habit of staying up late and sleeping in the morning: 夜をふかして朝寝の手) from a series published by Matsumura Tatsuemon titled Ukiyo shijû hatte (Forty-eight habits in the floating world: 浮世四十八手), circa 1821-22. The conceit of associating women with habits (good or bad) appeared in earlier ukiyo-e, for instance, Kitagawa Utamaro's series Nakute nana kuse (Seven habits to be without: なくて七癖), circa 1801, and Katsushika Hokusai's series titled Fûryû nakute nana kuse (Fashionable seven useless habits: 風流無くてななくせ) circa 1798. Other meanings of hatte (八手) in Eisen's series expand upon the idea, such as "method," "technique," or "trick." So it would seem that the two young women have not only slept in, but are preparing the meet the day with all the allure they might muster. An excellent single-figure ôkubi-e by Eisen is shown above right. It is titled Ki ga karusô (Cheerful-looking: 気がかるう) from the series Imayô bijin jûnikei (Twelve views of modern beauties: 今様美人拾二景). The courtesan is paired with an inset view of the Ryôgoku-bashi (Ryôgoku Bridge: 両國橋). The mitate here is a comparison between conventional scenic landscapes in and around Edo with a close-up view of a bijin. Here, she is tuning her shamisen (three-string musical instrument: 三味線), presumably while preparing to entertain a customer.

Eisen produced some excellent surimono (privately issued prints: 摺物). In the image below left, signed "Keisai" (渓齋), he designed a surimono (217 x 180 mm) depicting a fuguruma (book-cart: 文車) and byôbu (folding screen: 屏風) decorated with a peacock and plum blossoms , c. late 1820s. The format is the standard shikishiban (nearly square poem card: 色紙判) used for countless surimono of the period. The extensively applied metallic pigment is a copper-rich brass used to emulate gold, intended here to invest the still life with an elegance and opulence associated with courtly life or, in the more pedestrian realm, wealthy merchant families. One poem, signed Jôyôsha Mitsusada, speaks of the increasing fragrance of scented plum throughout the night. The second poem, by Ryûôtei Edo no Hananari, describes the cherry blossoms of Edo bursting into bloom as if the flowers were loosely robed dancers in the golden glow of spring (the reference to gold partly alluding to the gold on the byôbu). In the surimono below right, from circa 1830, two young women are shown gathering haru no nanakusa (the seven herbs of spring: 春の七草). Since the Heian period (平安時代, 794-1185), the herbs were collected on the seventh day of January in the first lunar month as a talisman to ward off disease. The herbs were seri (Japanese parsley: 芹), nazuna (shepherd’s purse: 薺), gogyô (cutweed: 御形), hakobe(ra) (chickweed: 繁縷), hotokenoza (henbit: 仏の座), suzuna (turnip leaves: 菘), and suzushiro (garden radish leaves: 蘿蔔). Five poems are signed by each of the authors: Kakeitei Masuka, Sessôan Matsukado, Shinettei Ikura, Yukinoya Morikage, and Shinratei Manzô (森羅亭萬象 1763-1831, leader of the group). The poetry club Manji-ren (卍連 a subgroup of the Yomo-gawa, the "All directions club," 四方側) is identified by its crest, which appears on the kimono of the kneeling woman and the obi of the standing beauty. The leader of the Yomo-gawa was the eminent poet Yomo Utagaki Magao (四方歌垣真顔 1753-1829).

_surimono_peacock_310w.jpg) |

|

| Keisai Eisen: Fuguruma (book cart) and byôbu decorated with a peacock and plum blossoms surimono, shikishiban (217 x 180 mm), c. late 1820s |

Keisai Eisen: Women gathering seven herbs of spring surimono, shikishiban (204 x 176 mm), c. 1830 privately issued by the poetry club Manji-ren |

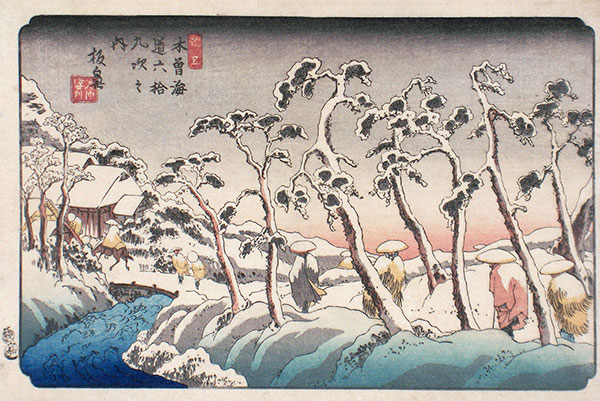

Eisen designed a number of notable landscapes. Among these, his 24 prints in the series Kisokaidô rokûjûkyû tsugi (Sixty-nine stations of the Kisokaidô Road: 木曾街道六拾九次之内) are most often encountered and widely admired. Eisen began the series in 1835, but left the project and was replaced by Utagawa Hiroshige, who completed the series sometime before 1843. Both artists likely adapted scenes from woodblock-printed guidebooks, as there is no evidence that either actually traveled along the Kisokaidô on a sketching tour. Eisen's view of Itahana (板鼻), shown below, is one of the last two station views he completed and is always found unsigned. The inscription at the top appears to be in Hiroshige's hand, suggesting that the design was left unfinished when Eisen ended his participation. It also offers a hint about why it is unsigned — the publisher Kinjudô might have wanted to emphasize Hiroshige's role in the series without abandoning Eisen's composition. Travelers are depicted approaching Itahana just after a heavy snowfall. There is a boldness and weight to the forms that scholars do not commonly associate with Hiroshige's generally more lyrical manner. The impression is a very early (probably the first) edition printing, with the bokashi ("shading off": 暈) in the lower part of the river and the greenish blue shading along the lower embankment. In later editions the red seal at the top left is different; the water in the stream is shaded nearer to the bridge; the hand-stamped kiwame / "Take" seal (Hôeidô publishing firm) in left margin is omitted, and the blue color on the figure's legs at the far right and on the legs of the two distant figures on the bridge is absent.

|

| Keisai Eisen (unsigned): Itahana (板鼻), from Kisokaidô rokûjûkyû tsugi (木曾街道六拾九次之内) Pub: Iseya Rihei (Kinjudô) and Enomotoya Kichibei (Hôeidô), ôban, c. 1835-38 |

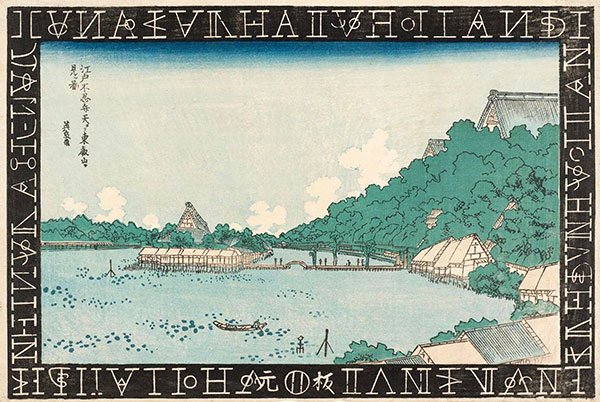

Also in the 1830s, Eisen produced a small group of images with unusual borders. One design, shown below is titled Edo Shinobazu Benten yori Tôeizan o miru zu (Tôeizan Temple seen from Shinobazu Benten Shrine in Edo: 江戸不忍弁天ヨリ東叡山ヲ見ル圖). Published by Ezakiya Kichibei (Tenjudô) circa early 1830s, it is from a series of famous places in Edo depicted within frames decorated with Western letters. Eisen was capitalizing on the vogue for foreign imagery. At the time, the Tokugawa shogunate enforced a foreign-relations policy called sakoku (closed country: 鎖國), in effect from 1641 until 1853. Without special permission, both foreigners and Japanese were forbidden to enter or leave Japan on penalty of death. Only the Dutch and Chinese were permitted to visit and trade directly, and their activities were restricted to the man-made island of Dejima ("Exit Island": 出島) in Nagasaki (長崎). The Japanese were endlessly curious about foreigners and the customs, including their language and their art. In Eisen's print, we can see the low horizon line common to Dutch paintings and prints. There is also an attempt at single vanishing-point perspective that the Japanese called uki-e ("floating pictures": 浮絵), which was adopted in the 18th century (see discussion included on the Toyoharu page). The fanciful border is composed of letters written backwards and forwards, at times approximating the spelling of "Holland."

|

| Keisai Eisen: Edo Shinobazu Benten yori Tôeizan o miru zu (江戸不忍弁天ヨリ東叡山ヲ見ル圖) (Tôeizan Temple seen from Shinobazu Benten Shrine in Edo) Publisher: Ezakiya Kichibei (Tenjudô), ôban, c. early 1830s |

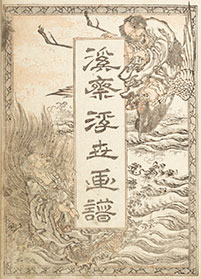

Included among the woodblock-printed books illustrated by Eisen is the three-volume ehon titled Keisai ukiyo gafu (Keisai's ketches of the floating world: 渓齋浮世画譜), as written on the title page (see image below left), although it is typically referred to as Ukiyo gafu. The set was published in Nagoya by Eirakuya Tôshirô (永楽屋東四郎 Tôhekidô, 東壁堂), who also issued Hokusai's famous Fugaku hyakkei (100 views of Fuji: 富嶽百景) in 1834-35 and the Hokusai manga (Sketches by Hokusai: 北齋漫画) from 1814 to 1878. The first two volumes of ukiyo gafu were drawn by Keisai Eisen Yoshinobu (渓齋英泉義信) and the third by Utagawa Hiroshige Ichiryûsai (歌川廣重一立齋). The long-term success of Hokusai's manga inspired Eirakuya to try his luck with publishing similar volumes by other artists. The Hokusai manner is clearly evident in Eisen's sketches (see below).

|

|

|

| Eisen: Keisai ukiyo gafu, c. 1820s (渓齋浮世画譜) Title page from vol. 1 |

Eisen: Keisai ukiyo gafu, c. 1820s (渓齋浮世画譜) Three scenes, from vol. 2 |

Eisen: Keisai ukiyo gafu, c. 1820s (渓齋浮世画譜) Assorted animals, from vol. 2 |

Timothy Clark (see ref. below) had this to say about Eisen's paintings: "Eisen painted a relatively large number of hanging scrolls of beauties, sometimes with particularly large (half life-size) figures drawn so that they appear to get larger the higher up the body they are viewed, giving them a very vivid appearance. The eyes are set wide apart with particularly luxuriant eyelashes, and the pupils always glancing off to one side, but otherwise the faces are not unlike those painted by Eizan."

In the painting below left, a young woman is shown arranging her hair as she looks at her reflection in a small pocket mirror. The tissues clenched in her teeth are mildly suggestive, signaling a passionate nature, at least to the voyeuristic male observer. On full display here is Eisen's skill in rendering the complex patterns of the robes and obi (sash: 帯). When compared to earlier artists such as Kiyonaga and Utamaro (and even early Eizan), bijin by Eisen and his contemporaries (Kunisada, Kuniyoshi, and other Utagawa print designers) appear earthier and more realistic. The first collectors of ukiyo-e in the West found this style "decadent" and were sometimes scathing in their criticism. Today, however, a long-deserved reappraisal has taken place, and such works are admired by many for their truthful expression of style and culture in the waning years of the Edo period.

The painting shown above right depicts two beauties on a veranda with autumn plants visible behind the women. The aki-no-nanakusa (seven plants of autumn: 秋七草) were hagi (bush clover: 萩); susuki (miscanthus, sometimes rendered as pampas grass 薄); kikyô (Chinese bellflower: 桔梗); kuzu (arrowroot: 葛); ominaeshi (maiden-flower: 女郎花); nadeshiko (pinks or wild carnations: 撫子); and fujibakama (boneset: 藤袴). The bijin on the right hands a saké cup to her companion. The vessel is inscribed with the characters for Bunchô (文晁), apparently referring to the painter Tani Bunchô (谷文晁 1763-1841), who presumably designed the cup. Once again, Eisen has expertly observed the textile patterns worn by the two fashionable women. The fabrics differ considerably from the somewhat ostentatious robes in the previous painting, as these show the type of restraint so admired by Edo sophisticates for whom iki (粋 or 粹) or unassuming elegance was the ideal. © 2020 by John Fiorillo

|

|

| Keisei Eisen: Young woman arranging her hair Painting: Ink, colors, and gold on silk, 851 x 340 mm Signature: Eisen sha, 英泉冩 (c. 1820s) |

Keisei Eisen: Women and autumn plants Painting: ink and colors on silk (888 x 372 mm) Signature: Keisai Eisen hitsu; seal: Keisai; (c. 1830s) |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Brooks, Kit: Something Rubbed: Medium, History, and Texture in Japanese Surimono. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University (PhD dissertation), 2017.

- Carpenter, John: Reading Surimono: The Interplay of Text and Image in Japanese Prints. Leiden: Hotei Publishing, 2008, p. 138, no. 11.

- Clark, Tim: Ukiyo-e Paintings in the British Museum. London: British Museum, 1992, pp. 196-197, no. 149.

- Forrer, Mathi: The Poetic Image: The fine art of surimono. Leiden: Hotei, 1987, C. Uhlenbeck, ed.).

- Izzard, Sebastian: Hiroshige / Eisen: The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidô. New York: Braziller, 2007, plate 15.

- Katz, Janice and Hatayama, Mami: Painting the Floating World: Ukiyo-e Masterpieces from the Weston Collection. Art Institute of Chicago, 2019, pp. 310-311, no. 144.

- Ota Museum of Art: Keisei Eisen ten botsugo 150 nen kinen (Exhibition of Keisei Eisen: 150th Anniversary of his Death). Tokyo 1997.

- Rappard-Boon, Charlotte van: Hiroshige and the Utagawa school: Japanese prints c. 1810-1860. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1984, pp. 138-139, no. 246.

- Segawa Seigle, C.: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1993, pp. 106-110.

- Suzuki, J. and Oka, I.: Masterworks of Ukiyo-e: The Decadents (vol. 8). J. Bester (ed.). Tokyo: Kodansha, 1969, pp. 89-99.

Viewing Japanese Prints |