Torii Kiyomasu II (二代目 鳥居清倍)

The image on the right portrays Yamashita Kinsaku I (初代 山下金作) as a peddler from a shop called the "Kame-ya" ("Turtle House": 亀屋). He is selling packets of of tooth-blackening powder (ohaguro, 鐵漿 or お歯黒 or 鉄漿), a cosmetic compound containing an oxidized mixture of iron filings, rice starch, tea, and vinegar to which pulverized gall nut was added. The practice goes back at least as far as the Heian period (平安時代 794 to 1185) when it used by noblewomen of the imperial court, but during the early Edo period, girls blackened their teeth as young as thirteen years of age; later, the practice began at seventeen. Young girls who trained to be prostitutes marked their coming of age with ohaguro. "Pleasure women" also used ohaguro as a sign that they were "married" to their customers. One theory has it that tooth blackening grew out of a cosmetic solution to dental carries. Another suggests that the practice developed from the Buddhist belief that white teeth revealed our animal nature and should be hidden. Here, the peddler is shown walking about town with a large case of cosmetics strapped to his back. The actor Kinsaku I is performing in the manner of a waka-onnagata (若女方) or male actor in a young-female role. This may be related to a circa 1727 performance of Hachinoki onna gokyôsho or some other staging of the various hachinoki mono (plays about the potted trees: 鉢の物) or adaptations of the Nô play Hachinoki (The potted trees: 鉢木). Often with Kiyomasu II, we encounter a sweetness and charm that marks his style of portraying onnagata (men in women's roles: 女方). Two examples are shown below. On the left, from circa mid-1720s, we see an unidentified actor performing as Yaoya Oshichi (八百屋お七), the doomed maiden who, not with malice, starts a destructive conflagration while attempting to reunite with her lover. She holds a flowering cherry branch from which a tanzaku (poem slip: 短册) flutters in the breeze. It is inscribed Koi-zakura (Cherry blossoms of love: 恋さくら). Yaoya Oshichi, the greengrocer's daughter, was first inspired by actual events in 1681-82. She was the subject of utazaimon (ballads), novels, puppet plays (the first possibly in 1704), and kabuki stagings (the first in 1706 in Osaka). One of the best known retellings was written by Ihara Saikaku (1642-93: 井原西鶴) not long after the incident; he included it in his Koshoku gonin onna (Five women who loved love: 好色五人女) in 1685. In one dramatization, the seventeen-year-old Yaoya sets fire to her home, thinking her family will be relocated to where her lover (Sahei or Kichisaburô, depending on the version) resides, but much of the city was destroyed, and she is punished as an adult by being burned at the stake. The image shown below right depicts Segawa Kikunojo I (初代 瀬川菊之烝) as the fox-woman Kuzunoha (くずのは). In Japanese folklore, the kitsune (fox: 狐) had the power to bewitch people, possess them, or take their human form (fox possession: 狐憑き or 狐付き). Among the best known fox tales were those recounting the life of Kuzunoha. The first theatrical drama was the puppet play Ashiya Dôman Ôuchi kagami (An imperial mirror of Ashiya Dôman: (蘆屋道満大内鑑) staged in Osaka in 1734. Kabuki's premiere followed in 1737 in Edo. Yomeiri Shinodazuma (The wedding of the wife from Shinoda Forest: 嫁入信田妻) is a later adaptation of the Kuzunoha tale. In the central story, Kuzunoha was saved from hunters by Abe no Yasuna (安倍保名), a twelfth-century nobleman. The grateful fox, in the guise of a maiden (or in some versions a princess), marries him and bears a child named Dôji (boy 童子 i.e., Abe-no-Doshi or Dofuji どふじ), who will grow up to become the renowned astrologer Abe no Seimei (阿倍清明). Eventually, Kuzunoha is compelled to abandon her human family and return to her fox-world in Shinoda Forest. The two most admired episodes are the kudoki (lamentation: 口説) scene in which the fox prepares to abandon her child and writes an emotional farewell poem, and the kowakare (child-separation: 小 分 か れ) scene when she looks upon Dôji for the last time. The design by Kiyomasu II portrays Kuzunoha in a moment of reflection. The chrysanthemums evoke her animal abode in Shinoda Forest, as do the climbing and coiling perennial vines and leaves of the Kudzu on the red-colored robe. The actor Kikunojo's [Segawa] crests appear on each sleeve. He leans upon a chest with a layout for sugoroku ("double sixes: 双六 a game somewhat like backgammon), which has powdered metallics (iron or brass filings) sprinkled on the left vertical side. The delicacy of the figure is a far cry from the rather massive forms used for women and actors by the earlier Torii artists.

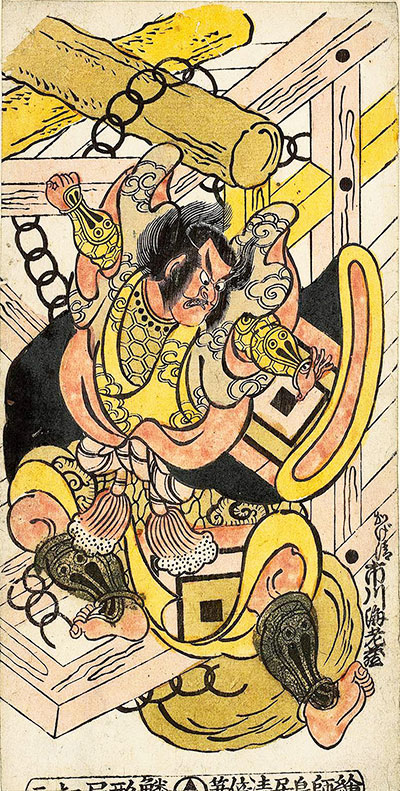

Kiyomasu II did not produce much in the way of thrillingly expressive portrayals of aragoto ("rough business: 荒事) performances. That was a specialty of his illustrious predecessors in the Torii line of artists (see Torii Kiyonobu I and Torii Kiyomasu I), in which some of their actors were shown in bombastic or explosive postures. However, Kiyomasu II came close from time to time. In the example shown below left, Ichikawa Ebizô II (二代目 市川海老蔵) performs as Kagekiyo (かげ清) in a production of Kasane gedatsu no hachisuba (累解脱蓮葉) in 7/1739 at the Ichimura Theater, Edo. The print is signed Eshi Torii Kiyomasu hitsu (Drawn by the painter Torii Kiyomasu: 絵師鳥居清倍筆). Taira no Kagekiyo (平景清 died 1196) was nicknamed "Akushichibyoe" (bad man of the seventh degree: 悪七兵ヘ景清) for killing his uncle, whom he mistook for his arch-enemy Minamoto no Yoritomo (源 頼朝 1147–99). Kagekiyo's original name was Fujiwara no Kagekiyo (藤原景清), but he was adopted by the Taira (Heike) and served them loyally for the remainder of his days. He was a formidable warrior, but was captured at a pivotal naval battle at Dan-no-ura (Dannoura no tatakai: 壇ノ浦の戦い) in 1185 when the Genji clan, led by Yoritomo, defeated the Heike forces. Exiled to a cave on Hyûga Island, Kagekiyo died of starvation in 1196. In the scene shown here, Kagekiyo, who had been imprisoned in Kamakura by the enemy Minamoto clan, breaks out of jail by smashing a huge boulder (now at his feet) through the wooden bars of his jail. The pose he strikes is spectacular, and the episode proved to be enormously popular in the kabuki theater, credited in one yakusha hyôbanki (actor critique: 役者評判記) as being a great hit (the play ran for a long three months) and likely the best-received performance that Ebizô had given in 25 years. Nearly a decade later, Ebizô II again played Kagekiyo, shown below right in a confrontation with his enemy Hatakeyama Shigetada (畠山重忠, 1164–1205), a warrior who had originally fought for the Taira clan, but switched sides to join the Minamoto at the battle of Dan-no-ura in 1185. Kagekiyo wrestles with a giant carp while Shigetada observes the struggle, emerging from a huge hollow in a willow tree. Kiyomasu II's print does not have the potency of the earlier Kagekiyo design, but it nevertheless captures some of the intensity to be found in aragoto performances. It is also a fine example of the two-color benizuri-e ("rose prints": 紅摺絵 early ukiyo-e made with block-printed red and green pigments), in this instance with exceptionally well-preserved colors.

Occasionally, Kiyomasu II produced prints that were in a mode different from his usual fare. In 1735 two leading artists, Nishimura Shigenaga (西村重長 c. 1697-1756) and Torii Kiyomasu II, embarked on a collaborative series titled Genji gojûyonmai no uchi (Genji in Fifty-Four Sheets : げんじ五十四まいのうち). Each artist was to design woodblock prints for the 54 chapters in the Genji monogatari (Tale of Genji: 源氏物語), with Shigenaga providing images for the first 26 chapters and Kiyomasu for the remaining 28. Today, only 23 designs are known, 17 by Shigenaga and six by Kiyomasu. Both artists relied on conventional Tosa-school style, including adding waka poems (和歌 verses of five lines and 31 syllables) within cusped clouds (kumogata 雲形) above the scenes. One of Kiyomasu's designs for the Genji series, shown below, includes a background of sprayed gray pigment through stencils ("blown shading" or fuki-bokashi: 吹きぼかし) to form the decorative images of an opened picnic box at the lower left and the Ichikawa acting clan's mimasu (three rice measures: 三舛) crest at the upper right. According to Louise Virgin (see Clark et al. reference cited below), the cartouche reads: On-haibako byôbu-e fusuma-e — Yamato beni-e kongen hanmoto rui nashi e-zôshi toiya Asakusa mitsuke-mae, Dôbô-chô Izumi-ya Gonshirô (Elegant designs for [pasting on] 'needle boxes', screens and sliding doors. Izumi-ya Gonshirô of Dôbô-chô, at the approach to Asakusa, inventor of Yamato beni-e and peerless wholesale dealer in illustrated books). Indeed, the publisher's declaration for the purpose of these prints (i.e., to be glued down and displayed on boxes, screens, and doors) probably helps to explain why so few of the designs are known to have survived. Kiyomasu II's design illustrates Chapter 27 when Prince Genji gives a lesson in playing the koto (a horizontal harp-like instrument: 琴) to a young woman named Tamakazura. When they finish and he is about to leave, he has his guard stir the flares lit in a hanging iron basket, telling her that an unlit garden on a moonless night can be frightening. Feeling both paternal and romantic, he then composes a poem: Kagaribi ni / tachisou koi no / keburi koso / yo ni wa taesenu / honô naruran (Flares rise / and drift as smoke / in this world my love / a flame / that will not be dispersed). In the image below, Genji stands in the center looking upon the seated Tamakazura, while his guard waits beyond the fence at the right where the iron basket hanging from a maple tree can be seen emitting flames.

Kiyomasu II had a few pupils, including Torii Kiyomitsu (鳥居清満 1735-1785) and probably Torii Kiyohiro (鳥居清廣 act. c. 1750-1776). © 2021 by John Fiorillo BIBLIOGRAPHY

|

Viewing Japanese Prints |

Torii Kiyomasu II (鳥居清倍), active circa late 1718-1760, was a woodblock-print designer, book illustrator, and painter during the early period of ukiyo-e. Thus, his active period spanned the production of monochrome prints, with many having brushed-on hand-coloring, through the years when two- and three-color designs with woodblock-printed colors came to define ukiyo-e in the 1740s-1750s. It remains unclear precisely what this artist’s relationship was to

Torii Kiyomasu II (鳥居清倍), active circa late 1718-1760, was a woodblock-print designer, book illustrator, and painter during the early period of ukiyo-e. Thus, his active period spanned the production of monochrome prints, with many having brushed-on hand-coloring, through the years when two- and three-color designs with woodblock-printed colors came to define ukiyo-e in the 1740s-1750s. It remains unclear precisely what this artist’s relationship was to