Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川國芳)

|

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川國芳) was the son of a silk dyer named Yanagiya Kichiemon. When he was about twelve years of age, Kuniyoshi was accepted as a student by Utagawa Toyokuni I. A prolific print designer, book illustrator, and painter, he produced more than 5,000 ukiyo-e print compositions. His subjects included warriors (musha-e), legends and folklore, kabuki actors (yakusha-e), women (bijinga), domestic scenes, manners and customs (fûzukuga: 風俗画), landscapes (fûkeiga), nature (animals and flora, kachôga), religious prints, memorial prints (shini-e), wrestlers, erotica (shunga), comic pictures (giga-e), games and pastimes, and trick pictures (komochi-e). Yet although Kuniyoshi designed prints in a wide variety of subject areas, he is most recognized for his prints depicting warriors, scenes of historical figures and events, and legends.

|

| Utagawa Kuniyoshi: Gyokukirin Roshungi (玉麒麟盧俊義; Ch., Lu Junyi, the Jade Unicorn) Series: Tsûzoku suikoden gôketsu hyakuhachinin no hitori The 108 Heroes of the Water Margin (通俗水滸傳豪傑百八人之一個), 1827-1830 (a few designs issued later) Woodblock print, ôban nishiki-e, middle sheet of triptych Publisher: Kagaya Kichiemon (加賀屋吉右衛門, Firm Name: Seiseidô, 青盛堂) |

Kuniyoshi's first known designs were produced for an illustrated kusazôshi gôkan (frivolous literature, 草双紙 in "combined volumes," 合卷). Written in 1814 by Taketsuka Tôshi, the work was titled Gobuji chûshingura (Chûshingura with a Happy Ending), a parody of the famous revenge tale Kanadehon chûshingura (Copybook of the treasury of loyal retainers: 仮名手本忠臣蔵) in which the mass seppuku (ritual suicide: 切腹) of the original version does not take place and all forty-seven rônin live long and happy lives. As for Kuniyoshi's his first single-sheet print, it appeared in 1815 — a portrayal of Nakamura Utaemon III as Shundô Jiroemon in Ori awase tsuzure no nishiki (Weaving a brocade of rags: 織合襤褸錦). His first known heroic triptych was published in 1818. However, from about that year until 1827, Kuniyoshi seems to have done little of any consequence.

Finally, Kuniyoshi gained widespread fame when he rocked the printmaking world, beginning in 1827, with his series Tsûzoku suikoden gôketsu hyakuhachinin no hitori (The 108 heroes of the Suikoden: 通俗水滸傳豪傑百八人之一個) in which he portrayed legendary Chinese heroes from a hugely popular semi-fictional saga, Tales of the Water Margin (水滸傳;, Ch., Sui Ho Chuan or Shui Hu Zhuan). Based on the fourteenth-century Chinese novel, The Suikoden was a rousing and bloody epic celebrating the exploits of a band of righteous outlaws led by Song Jiang, whose base of operations was an encampment by a marsh (the "water margin" of the title) on Mount Liang (Liangshan; Jp., Ryôsanpaku). Kuniyoshi's series never reached the full complement of 108 heroes, as only 75 heroes appear on 74 known ôban-size sheets. A large majority of the figures fill the pictorial spaces dynamically, their expressive faces accentuating the individuality of each character. Moreover, the exotic costumes, the ersatz European-inspired chiaroscuro, the dazzling range of weaponry, the diversity of poses, and the commanding visual presence and bristling energy of the figures all helped fuel a Suikoden print-collecting craze in Edo and Osaka.

The design shown above is the center sheet of a triptych, here depicting Gyokukirin Roshungi (玉麒麟盧俊義; Ch., Lu Junyi, the Jade Unicorn). The other two sheets portray, on the right, Sekihakki Ryûtô (赤髪鬼劉唐; Ch., Liu Tang, the Red-haired Devil), and on the left, two figures, Hakutenchô Riô (撲天雕李應; Ch., Li Ying, the Swooping Hawk) and Bossharan Bokukô (設遮攔穆弘; Ch., Mu Hong, the Invincible). The subject of the scene is a fight between Roshungi (a wealthy man and skilled warrior from Beijing) and the other three protagonists who are members of rival gangs. After a very long battle, Roshungi is captured, whereupon the bandits try to recruit him. He refuses and returns to Beijing. Later in the story, Roshungi finally becomes a member of the Ryôsanpaku gang.

When the Tenpô reforms of 1842 banned prints of beautiful women and kabuki actors, prints depicting warriors, legends, and landscapes became the life-blood of artists like Kuniyoshi. As a result he issued several large series of warrior prints in the 1840s. Yet even historical subjects could prove dangerous if treated in the wrong manner. In 1843, when Kuniyoshi designed a very popular satirical triptych of the shogun Tokugawa Ieyoshi and the earth spider, the woodblocks and remaining stocks of unsold prints were confiscated and destroyed, and Kuniyoshi was investigated and officially reprimanded.

|

| Utagawa Kuniyoshi: Kurô Hangan Yoshitsune at Horikawa Chapter 31, Maki-bashira (真木柱, Cypress Pillar) Series: Genji kumo ukiyo-e awase (源氏雲浮世画合) (A Comparison of Floating World Prints with the Cloudy Chapters of Genji), 1845-1846 Woodblock print, ôban nishiki-e Publisher: Iseya Ichibei (伊勢屋市兵衛), Seal name: hanmoto Iseichi (版元伊勢市) |

The illustration shown above is from one of the series issued while the Tenpô Reforms were still casting a shadow over print production. Titled Genji kumo ukiyo-e awase (A Comparison of Floating World Prints with the Cloudy Chapters of Genji: 源氏雲浮世画合), it was published by Iseya Ichibei circa 1845-46. The series is apparently complete in 60 known designs, 54 for each chapter in the Genji monogatari ("Tale of Genji") plus 6 supplemental designs (the latter titled Genji kumo shu-i, 源氏雲拾遺). The print shown here is number 31 (indicated in the lower left margin) corresponding to the Makibashira (The Cypress Pillar: 真木柱) chapter, with its title given in the middle of the scroll above, and the series title appearing at the top right on the scroll cover. The Genji-kô (Genji incense emblem) for chapter 31 is used as a repeated pattern on the scroll surrounded by a poem. A descriptive text by Hanagasa Karitsu appears below the scroll at the far left.

After the great victory on April 25, 1185 at Danoura in which Minamoto no Yoritomo (源頼朝 1147-1199) and his half brother Minamoto no Yoshitsune (源義経 1159-1189) defeated the Taira clan (平氏), Yoritomo, who would be designated as the first shogun of Japan, became unjustly suspicious and jealous of the brilliant military exploits of his younger brother. He refused to allow Yoshitsune entry into the headquarters in Kamakura, and instead sent him off to Horikawa in Kyoto. Yoritomo then secretly dispatched a warrior monk named Tosabô Shôshun to assassinate Yoshitsune. The attackers were defeated and Shôshun was captured and beheaded by the legendary Benkei, the warrior priest and ally of Yoshitsune. Yoshitsune took flight from Yoritomo's warriors, but in a final battle at Koromogawa on May 16, 1189 he committed seppuku (ritual suicide: 切腹) rather than be captured.

The scene in Kuniyoshi's print above depicts Kurô Hangan Yoshitsune as he grasps a pillar on the balcony of the palace at Horikawa. This gesture represents an obvious pictorial pun on the cypress pillar of the Genji chapter. It also connects Yoshitsune with the metaphorical meaning of "big size" used commonly in traditional Japanese poetry for the title word makibashira. At the far middle left there are military banners rising through the mist, which belong to Tosabô Shôshun and his warriors. The heroic figure of Yoshitsune standing on the railing and defiantly observing his attackers while arrows strike all around him makes this one of the more successful designs from the series.

|

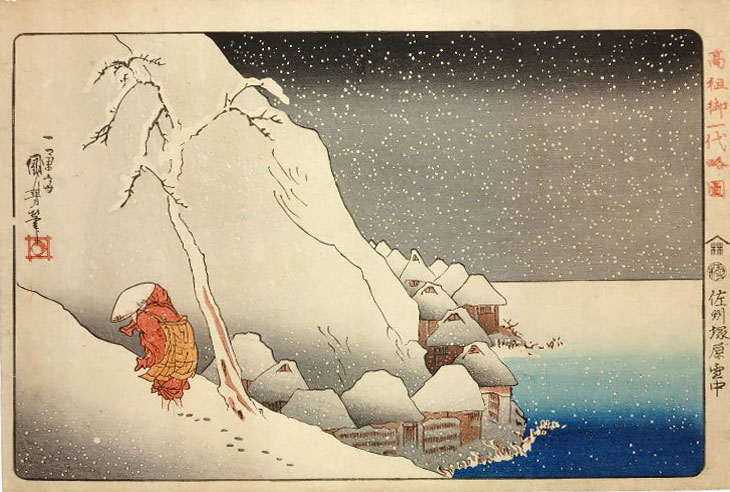

| Utagawa Kuniyoshi: Sashû Tsukahara setchû (Nichiren in the Snow at Tsukahara on Sado Island: 佐洲塚原雪中) Series: Kôsô goichidai ryakuzu (高祖御一代略圖) (Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest), c. 1835 Woodblock print, ôban nishiki-e Publisher: Iseya Rihei (伊勢屋利兵衛), Firm Name: Kinjudô (錦樹堂) |

Kuniyoshi produced fûkeiga (landscapes: 風景画) in several series, including five early productions in the 1830s: Tôto (The Eastern Capital: 東都) published by Yamaguchiya Tôbei c. 1833; Sankai meisan zukushi (Famous Products of Mountain and Sea: 山海名産盡), with figures and landscapes, published by Shin Iseya Kohei, c. 1833; Tôto meisho (Famous Views of the Eastern Capital: 東都名所), published by Kagaya Kichibei, c. 1834; Tôkaidô go-jû-san eki roku shuku meisho (Famous Views of the Fifty-three Stations of the Tôkaidô: 東海道五拾三駅四宿名所), co-published by Tsuruya Kihei and Tsutaya Kichizô, c. 1835; and Kôsô go-ichidai ryaku zu (Illustrated Abridged Biography of Kôsô: 高祖御一代略図), published by Iseya Rihei, 1835-1836.

A famous example from the last series is shown above, a portrayal of the Buddhist monk Nichiren (日蓮 1222-1282) making his way up a snow-covered hillside during his exile on Sado island. His banishment followed a series of letters he wrote to prominent leaders in which he directly provoked the major prelates of Kamakura temples that the Hôjô clan (北条氏) patronized, criticized the principles of Zen that were popular among the samurai class, critiqued the esoteric practices of the Shingon Buddhism (真言宗) just as the government was invoking them, and condemned the ideas underlying Risshû Buddhism (律宗) when it was enjoying a revival. Nichiren was arrested, but was spared execution, and instead was exiled to Sado Island.

There is ongoing debate over which impressions represent the earliest state. Currently, most scholars accept the state shown here with the horizon line as the earliest, and those without as later (see Clark ref. below). However, others find that there are impressions without the line that might be the earliest (see Forrer ref. below). If an impression without the break in the left border near the signature can be found without the horizon line, that would be conclusive.

|

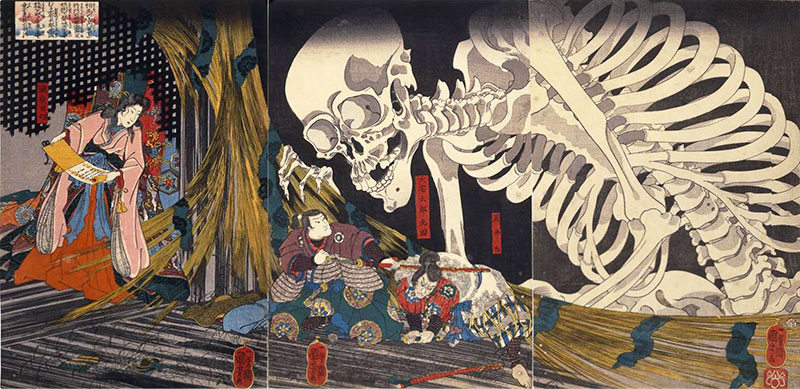

| Utagawa Kuniyoshi Sôma no furudairi ni Masakado himegimi Takiyasha yôjutsu o motte mikata o atsumuru; Ôya no Tarô Mitsukuni yôkai o tamesan to koko ni kitari tsui ni kore o horobosu (In the Ruined Palace at Sôma, Masakado's Daughter Takiyasha Uses Sorcery to Gather Allies; Ôya no Tarô Mitsukuni Comes Here to Investigate the Monsters and Finally Destroys Them) (相馬の古内裏に将門の姫君滝夜叉妖術を以って味方を集むる大宅太郎光國妖怪を試さんと爰(ここ)に来り竟(つい)に是を亡ぼす) Woodblock print, ôban nishiki-e, c. 1844-45 Publisher: Hachi (八) ? |

Among the most remarkable of all ukiyo-e prints is Kuniyoshi's spectacular portrayal of Takiyasha-hime (Princess Takiyasha: 瀧夜叉姫) summoning a giant skeleton-specter to intimidate Ôya Tarô Mitsukuni (大宅太郎光國) at her father Taira no Masakado's (平将門 died 940) ruined palace of Sôma (相馬) at Sashima in Shimôsa province. Takiyasha reads from a book of incantations while observing the conjured skeleton pulling down the reed blind and menacing Mitsukuni. Stories involving skeletons were popular in Edo-period Japan (as they are today), and one possible source for Kuniyoshi's print was a yomihon (sparsely illustrated "books for reading": 讀本 or 読本) of 1806 titled Utô Yasukata chûgi-den (Tales of Faithful Yasukata: 善知安方忠義伝), written by Santô Kyôden (山東京伝 1761-1816) and illustrated by Kuniyoshi's teacher Utagawa Toyokuni I, in which hundreds of skeletons form two armies and engage in a fierce battle. In Kyôden's fantasy novel, Takiyasha and her brother, Taira no Yoshikado (平良門), are the children of the historical warrior Taira no Masakado, who rebelled against imperial rule in the tenth century. In the Kyôden fiction, a character named Utô Yasukata is killed by the evil magic of Takiyasha and Yoshikado, but his relatives and their friends are eventually able to avenge his murder. Kyôden's very popular book was adapted for puppet and kabuki plays. Kuniyoshi designed several prints based on this story, including the celebrated triptych shown above. In regard to rendering the skeleton, Kuniyoshi probably knew Katsushika Hokusai's design of the ghostly skeleton of Kohada Koheiji (こはだ小平二 [小幡小平次)] ) pulling down a mosquito net from the series Hyaku monogatari (100 Ghost Tales: 百物語), circa 1833. Moreover, Dutch drawing manuals that included accurate illustrations of skeletons were also widely known in Japan from at least the late seventeenth century.

|

| Utagawa Kuniyoshi Chôô; Shiokumi goban-tsuzuki, sono yon (Zhang Heng; Five-sheet print of Collecting Brine, no. 4: 張橫; 汐汲五番其四) Set Title: Fuzoku onna Suikoden, ippyaku-hachinin no uchi (Elegant Women's Water Margin: From 108 Figures: 風俗女水滸傳, 壹百八人ノ内) Woodblock print, surimono, shikishiban (210 by 180 mm) c. 1828-30 Sponsor: Taiko ("Drum": 鼓) club of kyôka poets; Printer: suriko Shinzô |

Continuing with the Suikoden saga, Kuniyoshi also introduced its characters and themes in seemingly unrelated imagery called mitate ("likening pictures" or analogue images: 見立絵). These were, generally speaking, modernized literary and visual adaptations of classical themes or historical persons and events, often but not always with parodistic intent. In one instance, Kuniyoshi produced a pentaptych within a series of surimono (privately commissioned specialty prints: 摺物) titled Fuzoku onna Suikoden, ippyaku-hachinin no uchi (Elegant Women's Water Margin: From 108 Figures: 風俗女水滸傳, 壹百八人ノ内). One sheet, number 5, is shown above. On the surface, this is a pleasing portrayal of a young woman scooping up brine (seawater) that she will use to extract salt. Further afield, however, is the mention of Chôô (Zhang Heng, 張橫) in the inscription at the upper right, who in the Suikoden tale is a ferryman and strong swimmer determined to avenge his brother Zhang Shun's murder, After assimilating Shun's spirit, he succeeds in decapitating the enemy general Hô Tentei (Ch., Fang Tianding). In Kuniyoshi's surimono, the obscure pairing of a shiokumi (salt scooping-girl: 潮汲み or 汐汲み) with a legendary warrior figure is typical of mitate-e where the "vulgar" or ordinary is matched with the "refined" (zoku, 俗 and ga, 雅). Kuniyoshi's style of figure drawing falls entirely within Utagawa-school conventions, although by this time the young beauty is depicted with a short body type rather than the sometimes taller, more elegant women portrayed by the founder of the school, Utagawa Toyokuni I, in the 1790s-early 1800s, and instead coming closer to the bijinga designed by Utagawa Kunisada I during the 1810s.

Many surimono include poems that may or may not elucidate the imagery. Clark (see ref. below, p. 129, no. 50.2) summaries as follows: "The three verses (right to left) are by Wasuitei Masane, Yamato Watamori, and Dondontei, respectively. They describe how at dawn in springtime the tide is so high and the atmosphere so calm that the brine cannot be fully scooped. Spring is priceless, like the reflection of the first rising sun of the New Year in the water in the bucket. The salt-gatherers' long, untied tresses are wet and alluring, resembling the new, pale green branches of a willow. Matsuri ga Waturu ('Parade Passes By') was the leader of the Taiko ('Drum': 鼓 also 皷) club of kyôka [playful verses: 狂歌] poets, whose verses appear on all five sheets. He also used the name 'Dondontei', in imitation of the sound of a drum."

Utagawa Kuniyoshi's Names

Surnames:

Surnames:

Utagawa (歌川)

Igusa / Ikusa (井草) later family name

Personal names:

Yoshisaburô (芳三郎) childhood name

Magosaburô (孫三郎)

Tarôemon (太郎右衛門)

Art Name (geimei):

Kuniyoshi

(國芳)

Art Pseudonyms (gô):

Ichiyûsai (一勇彩)

Chôôrô (朝櫻楼)

Ikusa (井草)

Saishôsa (採芳舎)

Sekkoku (雪谷)

Senshin (仙真)

Poetry Name (haimyô):

Ryûen (柳燕)

Pseudonym for shunga or erotic prints (ingô):

Ichimyokai Hodoyoshi (一妙開程芳)

Pupils of Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Kuniyoshi had an enomous number of students, although the vast majority were very minor artists of little or no consequence. Their associations with Kuniyoshi ranged from long-term apprenticeships in the studio to those who benefited from some brief tutelage by the master. More than 70 names are listed below; no doubt, others remain to be discovered.

Harusada II (春貞 1830-87, act. c. 1848–1855; gô: Yasukawa 保川); Kyoto artist

Kyôsai (暁齋 1831-89; Family name: Kawanabe Nobuyuki 河鍋陳之, used various gô)

Tomiyuki (富雪 c. 1848–1850s; gô: Rokkatei (六花亭 or 緑華亭), Senkintei (千錦亭); a possible student

Yono (世の)

Yoshiaki (芳明)

Yoshichika (芳近 ?-1868)

Yoshiei (芳栄, ?-1869)

Yoshifuji (芳藤 1828–87, act. c. late 1850s; gô: Ichiôsai [Ippôsai] (一鵬齋芳藤) Osaka artist

Yoshifusa II (芳房 1837-1860)

Yoshifusa-jo I (芳房女 act. c. 1850)

Yoshigiku (芳菊)

Yoshigiri (芳桐)

Yoshiharu (芳春, also 芳晴, 1828-1888; gô: Ikusaburô 幾三郎)

Yoshihide (芳秀 1832-1902)

Yoshihide (芳栄)

Yoshihiko (芳彦)

Yoshihiro (芳廣, ?-1884)

Yoshihisa (芳久 act. c. 1862-63)

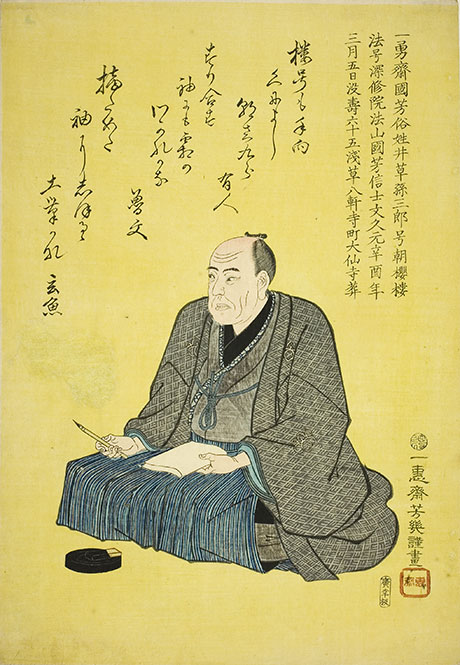

Yoshiiku (芳幾 1833-1904), designed memorial portrait of Kuniyoshi in 1861, shown above right

Yoshijo (芳女 act. end Edo period or c. 1848-64?)

Yoshikabu (芳蕪)

Yoshikado (芳廉, act. c. 1850)

Yoshikage (芳影)

Yoshikage (芳景, ?-1892)

Yoshikane (芳兼 1832-1881)

Yoshikata (芳形 act. c. 1841-1864)

Yoshikatsu (芳勝 act. c. 1850 or c. 1848-64?)

Yoshikazu (芳員 act. 1850-60)

Yoshikiyo (芳清)

Yoshikono (act.. c. 1850)

Yoshikoto (芳琴 act. c. 1852–56; gô: Ittôsai 一樋齋)

Yoshikuni (芳州) act. beginning Meiji; diff. from Osaka artist Yoshikuni 芳國 act. c. 1813–32)

Yoshikuni (芳國 act. c. 1850; diff. from Osaka artist Yoshikuni 芳國 act. c. 1813–32)

Yoshimaro (芳麿)

Yoshimaru I (芳丸 act. c. 1850)

Yoshimaru II (芳丸 二代, 1844-1907)

Yoshimasa (芳政 act. c. 1830-60)

Yoshimasu (芳升)

Yoshimi (芳見)

Yoshimitsu (芳満 1837-1910)

Yoshimori I (芳盛 1830-85)

Yoshimoto (芳基)

Yoshimune I (芳宗 1817-80)

Yoshimura (芳村 also 芳邨 1846-?)

Yoshinaka (芳仲)

Yoshinao (芳直 act. 1854-56 Edo)

Yoshinobu (芳延 1838-1890 Edo)

Yoshinobu (芳信 act. 1860s Edo) diff. from Osaka Yoshinobu who used gô: Ippyôtei (一瓢亭), Ippyôsai (一瓢齋)

Yoshisada (芳貞 also signed Kiyonobu 清貞, act. Meiji period)

Yoshisato (芳里 act. c. 1850)

Yoshisato (芳郷)

Yoshisen (芳仙)

Yoshishige (芳重, also written 吉重, act. c. 1840-55)

Yoshitada (芳忠 act. c. 1850)

Yoshitaka (芳鷹 act. c. 1850s)

Yoshitama-jo (芳玉女 also signed Shimizu 清水, 1836-70 female), also a pupil of Shibata Zeshin (柴田是真 1807-91)

Yoshitame (芳為)

Yoshitani (芳谷)

Yoshitatsu (芳辰)

Yoshiteru (芳照 act. 1850-90)

Yoshiteru (芳輝 1808-91)

Yoshitomi (芳富 act. c. beginning Meiji period)

Yoshitora (芳虎 act. c. 1830-1870)

Yoshitori-jo (芳鳥女 also signed Kuniyoshi musume 國芳女, musume Tori 女登里, Tori-jô 登理女 1797-1861 female)

Yoshitoshi (芳年 1839-92)

Yoshitoyo (芳豊 1830-66), Edo artist who also studied with Utagawa Kunisada I

Yoshitoyo (芳豊 died 1862, act. c. 1851–58; gô: Hokusui 北粋, 北翠, 北醉, 北粹, Gansuitei 含醉亭) Osaka artist

Yoshitsuna (芳綱 act. c. end Edo period or c. 1848-64?)

Yoshitsuru I (芳鶴 also written 芳霍 1789-1846)

Yoshitsuya I (芳艶 1822-66)

Yoshiume (芳梅 1819–79, act. c. 1841–50s; surname: Nakajima 中島; gô: Ichiôsai (一鶯齋), Yabairô (夜梅樓) Osaka artist

Yoshiyuki (芳雪, also written 蕙雪, act. c. 1850s - 1860s; gô: Ichireisai 一嶺齋)

Yoshizane (芳真)

©1999-2019 by John Fiorillo

See also the discussion of a Kuniyoshi print used to illustrate the Reading of Inscriptions and Seals.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Clark, Timothy: Kuniyoshi from the Arthur R. Miller Collection. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2009.

- Forrer, Matthi: The Baur Collection, Geneva: Japanese Prints, Vol. II. Genève: Collections Baur, 1994, no. G365.

- Inagaki, S.: "Kuniyoshi's Caricatures and Edo Society," in: Schaap, R.(ed.): Heroes and Ghosts: Japanese Prints by Kuniyoshi 1797-1861. Leiden: Hotei Publishing, 1998, pp. 241-242, fig. 17.

- Klompmakers, Inge: Of Brigands and Bravery: Kuniyoshi's Heroes of the 'Suikoden'. Leiden: Hotei Publishing, 1998, pp. 9-17.

- Nagoya City Museum (along with Chiba City Museum of Art, Suntory Museum of Art, and Nihon Keizai Shinbun, Inc.), Tanjobi 200 nen kinnen Utagawa Kuniyoshi ten (Commemoration of the bicentenary of the birth of Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Exhibition catalog, 1996.

- Robinson, B.W.: Kuniyoshi: The Warrior Prints. Oxford: Phaidon, 1982, pp. 22-24 and 129-130.

- Schaap, Robert: Heroes & Ghosts: Japanese prints by Kuniyoshi 1797-1861. Leiden: Hotei Publishing, 1998.

- Suzuki, Jûzô: Kuniyoshi. Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1992.

- Ukiyo-e-shi sōran (浮世絵師総覧), "Comprehensive Bibliography of Ukiyo-e Artists." (Last accessed May 19, 2021).

- Varshavskaya, Elena: Heroes of the grand pacification: Taiheiki eiyû den. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing, 2005.

- Weinberg, David: Kuniyoshi: The faithful samurai. Leiden: Hotei Publishing, 2000.

Viewing Japanese Prints |