Hishikawa Moronobu (菱川師宣) By the mid-1670s Moronobu had already become the most important ukiyo-e printmaker, a position he maintained until his death. He produced more than 100 illustrated books (around 60 are signed by him), perhaps as many as 150, although attributions to him for the many unsigned examples remains challenging. Some progress was made in 1926 when the confusion between Moronobu's works and those of Sugimura Jihei was alleviated to a great extent by the art historian Shibui Kiyoshi (see ref. below), which then provided other researchers with a basis for establishing differences in style between the two leading artists. Very few of Moronobu's single-sheet prints have survived, and most, if not all, are unsigned. Among these single sheets are erotic album prints. Moronobu was not the "founder" of ukiyo-e, as some early scholars surmised. Instead, with Moronobu we find an assimilation and further cultivation of rudimentary ukiyo-e designs by previous artists (some anonymous). What Moronobu accomplished was a consolidation of genre and early ukiyo-e painting and prints, and a crystallization of those previous efforts into a fully developed art form. By doing so, Moronobu established an assertive style that would set standards for generations of artists who followed. Moronobu's mastery of line has often been cited in laudatory assessments of his oeuvre, as well as his harmonious and interactive arrangements of figures. The kakemono-e (hanging scroll picture: 掛物絵) shown at the top right is the sort of Moronobu design that became a model for bijinga (pictures of beautiful women: 美人画) for generations of artists. Signed Yamato-e Hishikawa Moronobu zu (Illustration of a Japanese picture by Hishikawa Moronobu: 日本絵菱川師宣圖), the painting is done with ink and colors on silk. The image area measures 686 x 312 mm. Moronobu likely painted this work late in life, circa 1690. The beauty's tilted, oval-shaped head was part of Moronobu's visual vocabulary, likely influenced by Tosa-school (土佐派) works such as the countless paintings and illustrated books on the Genji monogatari (源氏物語) or Ise monogatari (伊勢物語). Moronobu's focus on the glories of kimono design became a central theme used by other ukiyo-e painters and print artists, especially the Kaigetsudô in the early years. So, too, is the gesture of the young woman lifting the front of her long robes to accommodate walking. Moronobu took his interest and expertise in kimono design a step farther by producing sketches for hinagata-bon (pattern books: 雛形本) such as Kosode no sugatami (Kosode in a full-length mirror: 小袖姿見) published by Urokogataya Sanzaemon (鱗形屋三左衛門) in 1683. The paired pages throughout the book display a kimono design on the left and, on the right, au courant young women and men dressed in the latest kimono fashions, accompanied by commentary, as in the illustration shown below.

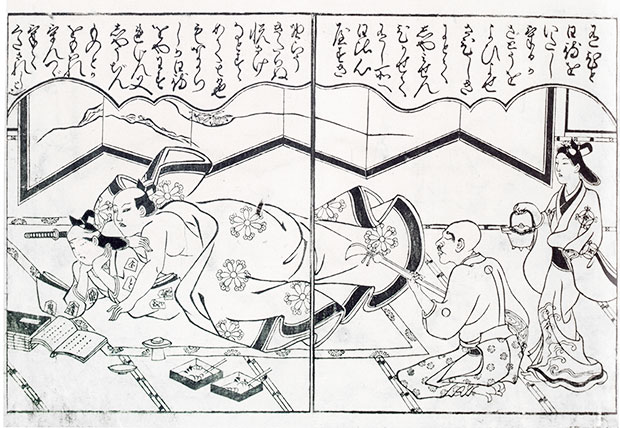

Moronobu's earliest erotic book was Wakashu asobi kyara no makura (Games with young men: fragrant pillow: 若衆遊伽羅枕) from 1675, so it is also his first book illustrating nanshoku (male-male love or male Eros: 男色). The Wakashu asobi is unsigned but universally attributed to Moronobu. The book contains 25 double-page shunga (explicit erotica or "spring pictures": 春画), which in Moronobu's day were actually called makura-e, or "pillow pictures": 枕絵). Moronobu offers up in graphic detail the sexual engagements of adult males and youths, presenting a record of some of the prevailing sexual customs of the period, or what came to be called shudô ("way of youths": 衆道), an abbreviation for wakashudô. It is also considered Moronobu's first ehon in his mature style of composition and figure drawing. The example shown below is the less-explicit frontispiece, a scene described in cursive script in the upper cusped section as one in which an older man, intent on spending the night in ritual purification, hires a blind shamisen player to help keep him awake. When a young kabuki actor stops by, the older man offers him some saké, and before long, the two are under the bed-covers together.

Moronobu's print shown below qualifies as an abuna-e ("dangerous picture" or risqué print: 危絵), a non-explicit erotic design of a type often found as the frontispiece to shunga sets or occasionally interspersed among the explicit sheets. In many of his best designs, Moronobu was inventive in his use of curvilinear forms juxtaposed against straight verticals and diagonals. Moronobu's formalism is evident here, with curves and straight lines balanced in near-perfect proportion. As for the amorous couple, the seduction has just begun with the loosening of the woman's obi (sash: 帯). Erotic signifiers enhance the scene. For example, the young beauty raises her right sleeve toward her mouth in a conventional gesture of suppressed emotion. Water imagery evokes the woman's sexuality, with feminine or yin erotic symbols in the garden stream behind the lovers and in the waves on the robe of the young gallant, while the flowering plum on the tsuitate (single-panel standing screen: 衝立) serves as a metaphor for male or yang sexuality.

Another design from the same period, circa early 1680s, further amplifies the emotive power of embracing lovers through posture and energetic linework. The two figures blend into a mass of flowing lines as the young man reaches under his lover's robe while she shyly lifts a sleeve to hide her arousal. The composition is divided into three areas: the flowers and grasses, the lovers, and the river before which a sword and scabbard are placed against a tree. Each section has a distinct visual impact. The autumn grasses stand upright and direct, the lovers form a complex interplay of lines and shapes communicating fervor, and the river and tree are rendered in a loose swirl of undulating lines. Some of Moronobu's prints are found with hand coloring, but this example is a sumizuri-e (print with black pigment only: 墨絵) in its original, uncolored state. There is something elemental in Moronobu's mature line work and figure placements in black and white prints that can sometimes be compromised when hand-coloring is added and produces decorative effects. Unadulterated sumizuri-e still suggest a range of tonal values, with emphasis on the shape and movement of the lines and the contrasting values of the white spaces.

A scene from one of the interior pages of a shunga album is shown below. In this example, a large ôban, hand-coloring has been applied in limited fashion and so the strength of the forms and lines remains relatively undiminished. The embarrassed maid looking back as she walks away from the amorous pair was the sort of popular voyeuristic theme in shunga that one encounters throughout the history of Edo-period ukiyo-e.

A view by Moronobu of the Takashima-ya (高嶋屋) brothel in the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter is shown below in a large ôban (286 x 457 mm) hand-colored sumizuri-e. The house has on display some of its low-ranking tsubone-jorô ("compartment prostitutes": つぼね女郎 or 局女郎) who are seated behind a cage-like display area, in effect, a latticed showroom, which is sadly indicative of the indentured servitude suffered by the women. Closest to the prostitutes are a samurai wearing a amigasa (woven or sedge hat: 編笠) intended to conceal his identity (the shogunate deemed it inappropriate for samurai to visit the Yoshiwara) and a figure with a shaved head who trails behind. On the far right, a woman may possibly be negotiating arrangements for a tryst with a customer. It is said that Moronobu was married to a former prostitute from whom he gained an insider's understanding of the world of pleasure women. The scene has the hallmarks of fûzokuga or genre pictures, that is, views of customs and manners among the urban population of Japan. Moronobu painted a large and very long handscroll with various scenes of the Yoshiwara such as this one, one of which also includes the Takashima-ya bordello (see Allen 2015 ref. below).

As a knowledgeable observer of the Yoshiwara, Moronobu sketched and painted many scenes from the world of sexual dalliance. In the following painting on silk (292 x 466 mm), circa late 1680s, five courtesans have gathered to play music, read books, and relax. One of the beauties plays a shamisen, as does a male musician at the far left (possibly a blind musician). A two-panel byôbu (floor screen: 屏風) at the top left is decorated with a scene of a red sun and chrysanthemums. Two small red seals above the flowers on the screen identify Hishikawa Moronobu as the artist. The woman on the far right wears a robe decorated with characters meaning hana (flower: 花) and sakura (cherry: 桜). Hana was a euphemism for something beautiful, or more specifically, for a beautiful woman or courtesan. Sakura evoked the aesthetic of transient beauty for its briefly flowering blossoms in early spring. It was a female flower, and by extension, a referent to youthful love and sex.

Moronobu produced a number of fûzokuga in large painted-screen formats. One such unsigned pair (six panels each) attributed to Moronobu includes in one of the six panels a wide view of the Nakamura kabuki theater in Edo circa 1690. Observing from right to left, the first two screen panels focus on crowds gathering outside the theater entrance as barkers announce the performances of the day. The ichô-mon (ginkgo-leaf crest: 鴨腳樹紋) of the Nakamura-za is emblazoned on three sides of a blue banner hung from the yagura (櫓 or 矢倉), the boxed turret or tower mounted above the theater entrance. In part, yagura signified that the theater had an official license to host performances. In Moronobu's day, there was a drum in the yagura that was beaten to open or close a performance each day. In the next four panels, theatergoers can be seen sitting on the ground before the stage, on which a flurry of activity is taking place as a long line of dancers entertains the audience. The complete two-screen work (12 panels in all; the other screen not shown here depicts dressing rooms and a male bordello attached to the theater) has been designated a jûyô bijutsu hin (Important art object: 重要美術品) by the Japanese government, whose aim is to identify certain works of significant historical and cultural importance, register the patrimony of such art objects, and prevent their unrestricted international sale. (A similar six-panel screen, also by Moronobu, is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, no. 79.468-469; see Morse ref. below.) There is insufficient space on this web page to illustrate effectively such panoramic screens; nevertheless, what is shown below are the six panels of the right-hand screen, and a detail of the the two panels on the far right. From these views one can sense how skilled Moronobu was in portraying panoramic scenes involving large crowds where the rendering and distribution of figures display a convincing naturalism by means of postures, gestures, and movement. © 2020 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

|

Viewing Japanese Prints |

Hishikawa Moronobu (

Hishikawa Moronobu (

Moronobu's first signed ehon (illustrated book: 絵本) was published in 1672 by Tsuruya Kiemon (鶴屋喜右衛門), titled Chû-iri kashira-zu buke hyakunin isshu (100 poems by 100 warrior poets, annotated and illustrated: 注入頭圖武家百人一首). The colophon gives the artist's name as eshi Hishikawa Kichibei (Painter Hishikawa Kichibei: 絵師

Moronobu's first signed ehon (illustrated book: 絵本) was published in 1672 by Tsuruya Kiemon (鶴屋喜右衛門), titled Chû-iri kashira-zu buke hyakunin isshu (100 poems by 100 warrior poets, annotated and illustrated: 注入頭圖武家百人一首). The colophon gives the artist's name as eshi Hishikawa Kichibei (Painter Hishikawa Kichibei: 絵師