Clifton KARHU (クリフトンカーフ)

|

Clifton Karhu (1927-2007 pronounced "Kurifuton Kafu" in Japanese クリフトンカーフ) was born in Duluth, Minnesota into a family of Finnish descent. From 1947 to 1949, during the post-war Allied occupation, he was stationed for a year in the port city of Sasebo, Nagasaki, with an assignment as a military artist. After leaving Japan (with regret) and returning to the U.S., he studied sketching and oil painting at the Minneapolis Institute of Art for a year and a half from 1950 to 1952. He questioned his commitment, however, to the field of art and decided instead to study theology. Choosing to become a lay missionary, he requested a posting in Japan, arriving there in 1955 and residing first in a small village in Shiga.

|

| Clifton Karhu: Nishi Hanami-koji (西花見小路), Gion (祇園)in rain, 1973 Woodcut; edition 50; 410 x 320 mm |

At that time, Karhu lacked Japanese language skills, which he found too restricting in his engagement with the local society. So he moved to Kyoto, where he had more opportunities to study the language and culture, which he did for two years. He said that, "As I look back on it, I realize that the calligraphy practice ... writing Japanese characters with their unique balance and design, had a great influence on my [later] pictures." Once he had become sufficiently skilled at reading and writing Japanese, he returned to his missionary work, but, again, had doubts about what he truly wanted to do.

Karhu decided to give up missionary work and moved to Gifu prefecture, living with his family, but without an income. He spent his days fishing and eventually began to sell some of what he caught in the Nagara River to local restaurants. (It is said that Karhu was especially skilled at freshwater fishing.) The income from selling fish was too meager to sustain his family, so he turned to teaching English. He met an oil painter named Hattori who awakened Karhu's dormant love for painting in oils and watercolors. Mr. Hattori encouraged him to hold a show of his works, and helped him secure gallery space. Karhu's first exhibition of paintings and watercolors took place in 1961 at the Shingifu Gallery in Gifu City. Later that year some pictures from that show were awarded first prize by the Central Pacific Art Society. In 1963, Karhu had successful exhibitions in 16 major cities in Japan as well as others in Hong Kong, Australia, Europe, and the U.S.

Despite his initial success with watercolors, oils, and Japanese-style paintings, Karhu again began to wonder about the direction his life was taking. Complicating matters was the fact that, after five years in Gifu, his children were increasingly speaking only Japanese. So he and his wife decided to move the family to Kyoto in 1961 where they could enroll the children in an international school and so improve their English skills.

In Kyoto, his Karhu's changed forever when he was introduced to Tetsuo Yamada, the owner of a gallery in Gion selling ukiyo-e prints. Yamada, who was also an inportant exhibitor of contemporary artists, told Karhu that the woodcut medium would be better suited than painting for the strong lines in his art designs. As Karhu once said, "Strong black outlines are the keynote in my pictures, and I found that unlike oils or watercolors, prints enable me to harmonize vertical and horizontal lines much more effectively." Initially, Karhu struggled with carving his blocks. He visited Yamada occasionally and learned from him where he was going wrong in the cutting of the wood. By 1964 he mastered the basics and had his first print and watercolor show at the Yamada Gallery.

|

| Clifton Karhu: Kiyomizu-dera (清水寺), Kyoto, 1969 (woodcut) |

Even so, Karhu had yet another crisis in confidence until an encounter with a fellow artist and friend for whom Karhu served briefly as an assistant. This was Stanton MacDonald Wright (1890-1973) co-founder of Synchromism, an early abstract, color-based mode of painting. Wright asked Karhu, "Were it not for artists, what light would there be in the world?" These and other probing questions and encouragements had their effect, and Karhu finally decided upon art as his path in life.

Karhu also credited Wright with teaching him the basics of color theory, which became "firmly fixed" in his thinking for the remainder of his life. For instance, Karhu explained, "There are so many different kinds of red; how would you explain exactly the shade you mean? Wright's definition of red was the color with nor yellow or blue in it. The way to determine true red is by spreading red on a white sheet of paper and looking at it for thirty seconds. Then look at another white sheet, and the opposite color, green, will appear as an after-image. If that green has a yellowish or bluish tinge to it, the red was not true." Karhu selected his colors while being always attentive to the primaries red, blue, and yellow, which he called the "strongest in expressive power." So if he wanted to bring out the red as the most prominent color, he would not place a red next to a green, but rather use color mixtures like yellow-green or blue-green near the red. In that way, the red would be best complemented and a "color harmony would be achieved."

Karhu's two years of studying Japanese in Kyoto was, as he said, "deeply engraved in my memory. I thought of Kyoto as the thousand-year-old capital where all that was good in Japan was concentrated. There was manmade beauty here, very different from that of the Nagara River in Gifu. The simple beauty of the tile roofs, the houses in the small back streets, the latticed windows of Gion and Teramachi, the merchant houses of central Kyoto, the town houses — everything impressed me. I walked about the city and sketched them all."

In his work, Karhu did not concentrate on the famous places. It has often been said of that much of his subject matter focused on ordinary everyday things that people so often take for granted and hardly notice. "I don't need the exotic," he said, "I like to do the things around me that I see every day. I wasn't born in Japan, so maybe I can look at something and appreciate it more because it hasn't lost its importance for me." He recalled that, "In my early years in Kyoto, I sketched the town houses of the central city exclusively.... Little by little, I explored Gion, and eventually I made the latticed houses, the streets, the hanging blinds, and stuccoed walls the theme of my prints." Few human figures appear in his prints, but in many of his designs, the presence of people can be felt. For instance, umbrellas left outside a restaurant on a rainy evening brings to mind an image of customers inside, dining and drinking.

One of Kyoto's most famous streets is Nishi Hanami-koji (西花見小路) situated in Gion (祇園), the geisha district. The historic architecture along the street is one of the highlights, in particular the old narrow-facade merchant homes or townhouses (machiya: 町屋 or 町家), many of which now house restaurants. Karhu depicted many of these structures that are so intimately associated with Kyoto, as in, for example, the image shown at the top of this page. Karhu said of this print, "I like rain. When I hear rain falling, I cannot wait to get up and go outside. Rain quiets the heart and adds dignity to almost any scene. The tiled roofs and latticework of Gion are made even more somber by the rain."

|

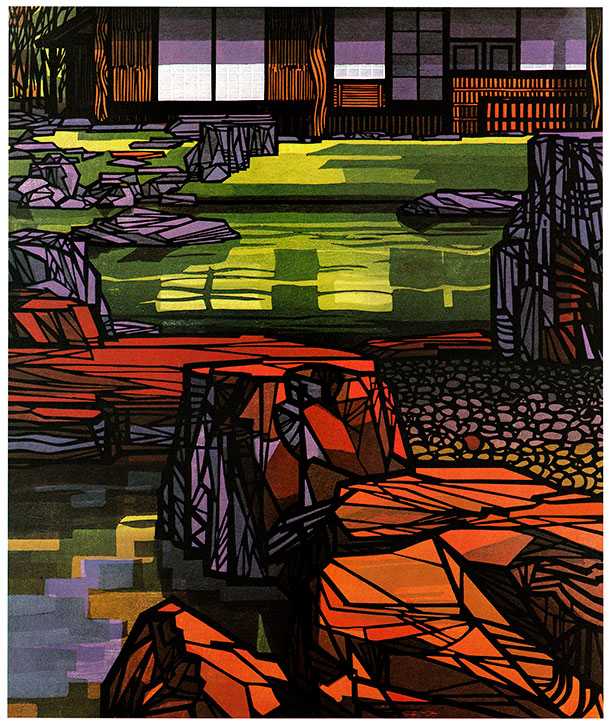

| Clifton Karhu: Katsura, Detached Palace (Imperial Villa), Kyoto Katsura Rikyû: (桂離宮), Woodcut |

Despite Karhu's general aversion toward images of famous sites, he had this to say about the exceptions to the rule: "I have printed comparatively few of the so-called famous sights of Kyoto. Their very fame impedes people's ability to enter into them, and without people, a picture cannot come to life. Nevertheless, I do have my favorites among the famous places. Foremost is Katsura Detached Palace. The beauty and balance of the shoin architectural lines remind me of Mondrian. This building was not built haphazardly like Gion, but as a perfect whole without a bit of waste." Although Karhu's views of Katsura do indeed include those that focus upon the architecture, the print shown immediately above features one of the gardens, about which he said, "The palace coexists with its gardens, and the natural setting cannot be ignored. The placement of the rocks in the garden is ingenious and highly artistic." In this view, the faceted forms and intense colors remind one of stained glass back-lit by sunlight. It is in images such as these that Karhu's greatest strengths can be found: Linear force and vivid color.

Over the years, Karhu was interviewed and his comments recorded, so we have for various works the artist's own commentaries. For example, Karhu found the Kiyomizu Temple (清水寺) in Kyoto a site of never-ending inspiration. He said, "Whenever foreign friends visit, I always bring them to Kiyomizu, where one may sense the strength of Kyoto traditions at a glance.... Built on pilings on a mountainside, Kiyomizu has stood watch over the capital for over a thousand years." In regard to one of his Kiyomizu designs (shown second from top on this page), he said, "This is the main hall viewed at sunset from the interior of the temple. The curves of the cedar-thatched roofs, the lines of the pillars and balustrades, the wood grain — all have a special meaning for me."

Several books have been published highlighting his prints, including, in 1979, Kyoto Seen Again (Kyoto saiken: 京都再見), which was published in English the following year as Kyoto Rediscovered (Weatherhill/Tankosha). In 1981, Kyoto Discovered (Kyoto hakken: 京都発見) was released, and in 2004, he published a collection of his prints, 77 Woodblock Prints by Clifton Karhu.

In 1995 Karhu moved to Kazuemachi, Kanazawa, Ishikawa, where he continued his printmaking for the next twelve years, focusing mainly on life in Kanazawa. Karhu died there from liver cancer in 2007. Yanis Art Japan, Ltd., opened the gallery "Karhu Collection" in the Kazuemachi Chaya District of Kanazawa. The gallery is in a renovated traditional tea house (chaya: 茶屋 or 茶店) that once served as Karhu's studio and home during his final twelve years. The gallery regularly exhibits (and sells) works by Karhu, including woodblock prints, ink paintings, and ornamental plates. There are 500 or so woodblock prints and ink paintings in a room renovated from a traditional earthen-wall warehouse.

The works of Clifton Karhu are in numerous private collections, as well as public institutions, such as the Cincinnati Art Museum; Harvard University Art Museums; Kunst Museum, Salzberg; Minnesota Museum of Art, St. Paul; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; National Museum of Australia, Canberra. Of particular interest, Karhu's twin brother Raymond donated around 80 works by Clifton Karhu to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. © 2021 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Blakemore, Frances: Who's Who in Modern Japanese Prints. New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1975, pp. 68-69.

- Karhu, Clifton: Kyoto Rediscovered. New York/Tokyo/Kyoto: Weatherhill/Tankosha, 1980. [Most of the quotations on this web page are taken from this publication.]

- Tolman, Mary & Norman: Collecting Modern Japanese Prints: Then & Now. Rutland, VT: Tuttle, 1994, pp. 97-100, 124-125, 228, plates 42, 52.

- Tolman, Mary & Norman: People Who Make Japanese Prints: A Personal Glimpse. Tokyo: Sobunsha, 1982, pp. 44-57, pl.

Viewing Japanese Prints |