Poetry on Prints

|

Poems on Ukiyo-e Prints

The poems accompanying ukiyo-e prints took various forms. A few useful, general categories may be identified as follows:

The poems accompanying ukiyo-e prints took various forms. A few useful, general categories may be identified as follows:

- Poems quoted verbatim from classical anthologies

- Poems that are close variants of classical verses

- Contemporary poems that rely upon allusions to classical poems

- New poems written in a classical style, but which are more or less contemporaneous with the print design

- New poems written in a modern style and composed for the particular occasion commemorated in the print design

- Memorial poems on death prints ('shini-e')

- Poems by actors, courtesans, writers, and other inhabitants of the "Floating World" that serve as commentaries upon the design or the person portrayed in the print.

Special mention should be made of the verse form known as kyôka ("playful verse": 狂歌), for it was an key element in much of surimono print design (see the Kyôka Craze).

One example of a standard edition print with a classical poem quoted verbatim is the design on the right by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) from a set of six ôban prints depicting the Rokkasen ("Six Immortal Poets") published by Ezakiya Kichibei circa 1810. The poet is Ono no Komachi (ninth century) and the poem reads: Iro miede / utsuou mono wa / yo no naka no / hito no kokoro no / hana ni zo arikeru. Komachi's expressive poem is a lament on a sad transience, the "fading away" of "altered color" (passion) in the "fickle hearts of men." Hokusai employed yet another level of "inscription," however, by cleverly incorporating the characters (stylized) for the poet's name in the outlines of the figure and screen. The characters for Ono no appear in kana on the left shoulder and sleeve (the second no upside down). Ko appears in kanji on the right shoulder, while machi can be seen only in part on the left side of the screen.

The word surimono translates literally into "printed thing" (摺物), but it typically indicates privately issued or commissioned prints that were distributed in limited editions and not placed on public sale. Surimono were made with poetic inscriptions or verses only, pictures only, or pictures accompanied by verses.

Both professional artists and amateurs designed surimono. Early verse surimono (haikai surimono) are known from at least as far back as the first decade of the 18th century. Although surimono were designed in a wide variety of sizes and formats, there was a large and rapid increase in surimono production in the first decade of the 19th century, with series and mulitsheet compositions becoming more common. This trend seems to have led to more standardization of the surimono design format, and thus after around 1810, surimono were most often printed on small, nearly square sheets around 20.5 x 18.5 cm in size in a format known as shikishiban (色紙判).

To distinguish the various surimono sizes from standard ukiyo-e sheet formats (such as ôban, aiban, chûban, koban, and hosoban), the following formats represent specific fractions of two standard sheet formats called ôbôsho ("large hôsho," approximately 42 x 58 cm measured horizontally) and kobôsho ("small hôsho). Actual surviving sheet sizes vary widely (and are often somewhat smaller) depending on the source of the original handmade papers and subsequent trimming during and after production. The sizes below are therefore only rough approximations.

- ôbôsho zenshiban: "large hôsho, complete sheet," the uncut large hôsho sheet (approx. 42 x 58 cm)

- kobôsho zenshiban: "small hôsho, complete sheet," a slightly smaller but uncut hôsho sheet (approx. 32 x 46 cm)

- jûnigiriban: "cut into twelve," the ôbôsho sheet cut once horizontally and six times vertically (approx. 20 x 10 cm)

- kokonotsugiriban: "cut into nine," cut three times each, vertically and horizontally (approx. 13 x 18 cm)

- yatsugiriban: "cut into eight,: the sheet cut once horizontally and four times vertically (approx. 20 x 14 cm)

- shikishiban: "square sheet," the sheet cut once horizontally and three times vertically (approx. 20 x 18 cm)

- ôtanzakuban: "large tanzaku (poem slip)," the sheet cut three times vertically (approx. 42 x 19 cm)

- chôban: "long sheet," also called nagaban, the sheet cut once horizontally (approx. 20 x 58 cm)

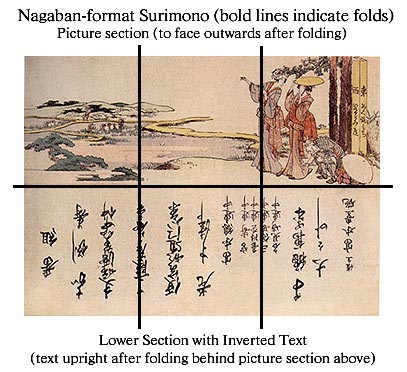

One popular size before 1810 was the yoko-nagaban surimono ("long horizontal surimono"), printed on an ôbôsho zenshiban (uncut large hôsho sheet). This format could accommodate large numbers of poems, or texts (as in the example shown above). If the ôbôsho sheet was not cut after printing but folded once horizontally, the poems or texts on one half of the sheet, which were printed "upside down" in relation to the picture, would be folded behind the section printed with the picture and thus made upright. Then the entire sheet would be folded in thirds. Often, however, these yoko-nagaban surimono had their text sections trimmed off (presumably many specimens suffered this fate because western collectors were interested only in the images). The surimono above was designed by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), signed Gakyôjin Hokusai ga ("Painted by Hokusai, Man Crazy About Painting"). It is trimmed slightly at the edges but otherwise intact. Although it depicts two women and a servant observing workers in a rice field, it is nevertheless an "announcement surimono" for a musical performance, with the names of the performers listed in the text. Hokusai designed a number of these types of surimono during the first decade of the nineteenth century.

The paper used in surimono production was typically of a high-quality called hôsho-gami and the finest printing

techniques were used to take advantage of these papers. Unlike standard ukiyo-e, the papers for surimono were frequently left

untreated with dosa (sizing; see papers), which meant they were more absorbent and thus

the resulting images were "softer" in appearance.

The paper used in surimono production was typically of a high-quality called hôsho-gami and the finest printing

techniques were used to take advantage of these papers. Unlike standard ukiyo-e, the papers for surimono were frequently left

untreated with dosa (sizing; see papers), which meant they were more absorbent and thus

the resulting images were "softer" in appearance.

The pictures were frequently accompanied by poems, with many exhibiting excellent calligraphy, and often the verses were intimately connected with the pictorial elements of the designs. The styles of calligraphy found in surimono were often variants of wayô ("Japanese style") writing that had been developed and standardized by the medieval period. 'Wayô' was derived from oie-ryû ("official family lineage") calligraphy, which followed orthodox methods used in courtier calligraphy manuals.

Very often the poems preceded the designs, while the designs frequently made possible a variety of interpretations of the verses. Many surimono were commissioned by poets, who were typically members of poetry clubs or groups (ren or gawa). The prints were then distributed to fellow members, friends, and colleagues to announce, commemorate or offer greetings for special events, the New Year (saitan surimono), the spring season (shunkyô surimono), year-end presents (seibo surimono), and so on. Other surimono were distributed for personal occasions or as announcements of important public performances. The yoko-nagaban surimono were often selected for such events (see nagaban above), partly because they could accommodate large numbers of poems. There were also 'daishô surimono ("long-short surimono")', which were sophisticated designs that incorporated calendrical information, usually incidentally and sometimes quite imaginatively, with symbols or design elements for the long and short months in a given year. They differed from the more literal and often less sophisticated egoyomi ("picture calendars") whose main purpose was to indeed provide explicit calendrical information.

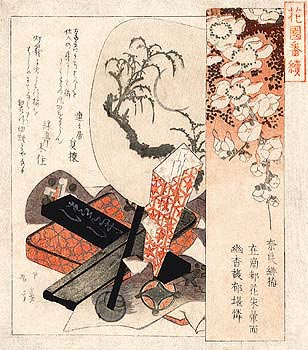

The "still life" was one subject that flourished in surimono design while being neglected in standard ukiyo-e printmaking. The design immediately above on the right by Totoya Hokkei (1780-1850) comes from a series made for the poetry club called the Hanazono-ren, which was led by the poet Garyôen Umemaro, whose name stands for a plum called garyô-bai ("bowing dragon plum"). The set is titled Hanazono bantsuzuki ("Series for the Hanazono Club"). More than 20 designs are known from the set issued in the year 1823, each with a narrow vertical panel depicting a particular species of plum blossom and a larger panel depicting a still life, sometimes rather complex in composition.

In the present example the plum is identified as Nara hibai ("Nara red plum"). A rigid fan (uchiwa) also shows a plum branch encircling a thin sliver of a new moon. A black ink stick is labeled seijô ("pure"). There are also two toothpicks propped up and wrapped in a decorated paper folder. Fans and ink sticks were well-known products of the Nara area, so their inclusion here would have been readily recognizable as such by Hokkei's contemporaries. The inscription in the vertical poem slip describes the fragrance of the blossoms as more than one can bear. The poems in the larger panel are by the poets Renrenkyô Kazumune and Ryokutei Mizumi (Rokutei Suezumi ?). The first poem mentions how well the Nara fan goes with the spring dresses sold in Nara's stores. The second poem declares that Nara plum branches will kindle fires to make Nara inksticks. Thus Hokkei's surimono serves as a celebration of the plum and spring as well as an advertisement for the famous products of Nara.

The illustration on the left is an impressive and luxurious surimono also by Totoya Hokkei. (By the 1820s Hokkei, a former

pupil of Hokusai's, had become one of the premiere designers of surimono.) This example is a vertical shishikiban diptych

issued for the rabbit year in 1831. It includes a reference to this zodiacal animal, for although it is difficult to see in

this small scanned image, a woman stands before the Moon Gate as she holds a white rabbit (an animal also associated with the

moon in Japanese folklore). Below the gate in the foreground a couple converse on a dark cloud outside the Palace of the Moon.

They have been identified as the legendary Chinese beauty Yang Guifei (Yôkihi in Japanese) and the magician Luo Gongyuan,

who served the emperor Xuan Zong. There was a famous Chinese poem about the two lovers called Ch'ang hen ko ("The Song

of Everlasting Sorrow") by Po Chü-i (772-846), whose poetry was widely quoted in classical Japanese literature

(where it was known as Chôgonka) and which was rewritten in the Japanese phonetic syllabary for greater accessibility

among the general population. There followed various adaptations in the Nô theater (Yôkihi by Komparu Zenchiku,

1405-1468) and in kabuki.

The illustration on the left is an impressive and luxurious surimono also by Totoya Hokkei. (By the 1820s Hokkei, a former

pupil of Hokusai's, had become one of the premiere designers of surimono.) This example is a vertical shishikiban diptych

issued for the rabbit year in 1831. It includes a reference to this zodiacal animal, for although it is difficult to see in

this small scanned image, a woman stands before the Moon Gate as she holds a white rabbit (an animal also associated with the

moon in Japanese folklore). Below the gate in the foreground a couple converse on a dark cloud outside the Palace of the Moon.

They have been identified as the legendary Chinese beauty Yang Guifei (Yôkihi in Japanese) and the magician Luo Gongyuan,

who served the emperor Xuan Zong. There was a famous Chinese poem about the two lovers called Ch'ang hen ko ("The Song

of Everlasting Sorrow") by Po Chü-i (772-846), whose poetry was widely quoted in classical Japanese literature

(where it was known as Chôgonka) and which was rewritten in the Japanese phonetic syllabary for greater accessibility

among the general population. There followed various adaptations in the Nô theater (Yôkihi by Komparu Zenchiku,

1405-1468) and in kabuki.

The emperor Xuan Zong became so obsessed with Yang Guifei that he neglected his responsibilities as supreme ruler. To restore order and save his empire from rebellious forces intent on deposing him and his consort, he was forced to permit the execution of his beloved Yang Guifei. In his despair he dispatched Luo Gongyuan to the Horai Palace in the Land of the Immortals, although it is transformed in Hokkei's print into the Palace of the Moon (where the emperor and his magician had once gone together in search of an elixir of immorality).

The loving couple Yang Guifei and Xuan Zong were popular tragic subjects in ukiyo-e prints and paintings, often while playing a single flute together (with underlying erotic overtones). In Hokkei's surimono there is an elaborate use of metallic pigments, most notably the gold-color brass for the clouds over the entire vertical pictorial space. The pigments are of high quality and applied in concentrated amounts, providing an atmosphere of elegance and luxury appropriate to the subject.

Even without the poetry this design provides the viewer with much information about the subject of Hokkei's surimono. The verses, nevertheless, do help to identify the purpose of the surimono, which was to offer a refined and metaphorical print design to celebrate the New Year in 1831. The first poem speaks of a loving couple viewing the towers of the palace in their first dreams of the New Year, which would have been considered a most auspicious sign. The second poem mentions a New Year's wine that stands for the elixir of immortality, where its value is compared to the mighty sum of 1,000 ryô (gold coins).

For other examples of surimono illustrated on this website, see Shôkôsai and Shigenobu II.

These was another class of high-quality prints that were not strictly surimono but which also included poems. These may be called deluxe prints (jôzuri-e, 上摺絵), and they can be distinguished from surimono by the presence of publishers' seals or sometimes by certain differences in key blocks or color blocks from earlier states that do not have such marks. The inclusion of publishers' seals indicates that the prints were sold to the public and thus they were not distributed privately as were true surimono. Nevertheless, deluxe editions of ukiyo-e prints were often the equal of surimono in the quality of their design, colorants, paper, and printing.

Some of the finest examples of deluxe printmaking came from Osaka. During the period before the Tenpô Reforms of 7/1842 - 1/1847 (Tenpô kaikaku, 天保改革) when prints related to the kabuki theater were banned, the vast majority were published in the ôban format. The illustration on the right depicts the onnagata Arashi Tokusaburô II as Kitsune Kuzunoha and Arashi Takejiro as her son Abe no Doshi. Kuzunoha was a fox (kitsune) who took human form and in the guise of a maiden (in some versions a princess), married Abe no Yasuna, a twelfth-century nobleman who had saved the fox from hunters. Kuzunoha bore him a child, who would become the future famous astrologer Abe no Seimei. Ultimately Kuzunoha was compelled by various circumstances (depending on the version of the dramatization or legend) to reclaim her fox nature and return to her natural home in Shinoda Forest. So with unbearable sadness she abandoned her husband and son after writing a famous farewell poem. (In the kabuki theater this was sometimes accomplished by writing with a brush held in the mouth, a sign of Kuzunoha's unusual nature.)

Some of the finest examples of deluxe printmaking came from Osaka. During the period before the Tenpô Reforms of 7/1842 - 1/1847 (Tenpô kaikaku, 天保改革) when prints related to the kabuki theater were banned, the vast majority were published in the ôban format. The illustration on the right depicts the onnagata Arashi Tokusaburô II as Kitsune Kuzunoha and Arashi Takejiro as her son Abe no Doshi. Kuzunoha was a fox (kitsune) who took human form and in the guise of a maiden (in some versions a princess), married Abe no Yasuna, a twelfth-century nobleman who had saved the fox from hunters. Kuzunoha bore him a child, who would become the future famous astrologer Abe no Seimei. Ultimately Kuzunoha was compelled by various circumstances (depending on the version of the dramatization or legend) to reclaim her fox nature and return to her natural home in Shinoda Forest. So with unbearable sadness she abandoned her husband and son after writing a famous farewell poem. (In the kabuki theater this was sometimes accomplished by writing with a brush held in the mouth, a sign of Kuzunoha's unusual nature.)

The print is by Shunkôsai Hokuei (active c. 1827-1836), a deluxe edition published by Honsei circa 1833, with the poem printed in silver-color metallics. It is signed Kitchô, a haigô (poetry name) that was also an alternate stage name for Tokusaburô II. The signature within the poem (urami Kuzunoha or "regretful Kuzunoha") expresses the fox's unwillingness to leave her husband and child. This type of scene is known in kabuki as kowakare ("child separation"). There is also a pun between her name 'Kuzunoha' and kudzu no ha, the "kuzu leaf" (arrowroot) that grows in the Shinoda forest. Of particular note are the first five characters of the poem, which are written backwards in Hokuei's design, a clever way of revealing the non-human nature of Kuzunoha. The poem may be read as: Koishiku ba / tazunekite miyo / izumi naru / shinoda no mori no / urami kuzunoha ("If you long to love me, / Search for me in / Shinoda no mori, / Izumi Province / with regret, Kuzunoha.").

The last illustration is a deluxe print issued at the start of 1837 as Hokuei's memorial print (shini-e or "death print"), for which the publisher Honsei used a preliminary Hokuei sketch from 1836. It depicts Nakamura Utaemon IV as the wrestler Iwagawa Jirokichi in the play Sekitori senryô nobori ("The Rise of the 1,000 Ryô Wrestler") performed in 3/1836 at the Kado Theater, Osaka.

The last illustration is a deluxe print issued at the start of 1837 as Hokuei's memorial print (shini-e or "death print"), for which the publisher Honsei used a preliminary Hokuei sketch from 1836. It depicts Nakamura Utaemon IV as the wrestler Iwagawa Jirokichi in the play Sekitori senryô nobori ("The Rise of the 1,000 Ryô Wrestler") performed in 3/1836 at the Kado Theater, Osaka.

The small cartouches identify the blcokcutters hori Toyo and Yamaki tô (the inclusion of the names of artisans was often a sign of a deluxe production). In addition to three poems, the publisher Honsei’s tribute to Hokuei includes a long inscription on the far right (first two vertical lines): Kojin Hokuei byôga no makura ni fude no owari to seshi kono saiga o azusa ni agete isasaka kôge no hashi to sen ("The late Hokuei painted this picture while on his sickbed. We offer this as a final farewell in memory of his work.").

The first poem on the right refers to Hokuei's artistic skill: Fudedake no / omokage / miyuru / oboro kana ("A brush of great height / Whose countenance appears / Through a moonlit haze."). Although we do not know how old Hokuei was at the time of his death, it appears that the second poem's springtime imagery alludes to Hokuei's unexpected early death: Kieta towa / uso no yoonari / haru no yuki ("It seems untrue - Vanished forever / Like Spring snow!"). The third poem, isolated and most significant on the left, is signed Kanjaku, the haigô of the actor Utaemon IV. It converts the common Taoist image of "Heaven's wide net" (used conventionally to suggest that all under heaven reap what they sow) into the metaphor of Hokuei's passing through a fishing net to attain his own salvation, made possible by his achievements as a master print designer: Shirauo no / ami no me kuguru / chikara kana ("With great power / The white fish passes through / The meshes of the finest net."). © 2001-2019 by John Fiorillo

For more about prints commemorating the deaths of actors, see shini-e.

For a discussion of related topics, please refer to the following links:

Viewing Japanese Prints |