Utagawa Hiroshige III (三代目 歌川廣重)

|

Utagawa Hiroshige III (歌川廣重 [三代]) 1842 / 1843-1894) was born Gotô Torakichi (後藤寅吉), the son of a shipbuilder in the Fukugawa (深川) district of Edo. He first studied as a teenager with Utagawa Hiroshige I (1797-1858) until the master's death. His early art name was Shigemasa (重政). In 1867, after Hiroshige II (1826-1869), a fellow pupil of the first Hiroshige, divorced the master's adopted daughter Otatsu, Gotô married her and took the name Utagawa Hiroshige II, but by 1869, he had decided to call himself Hiroshige III.

|

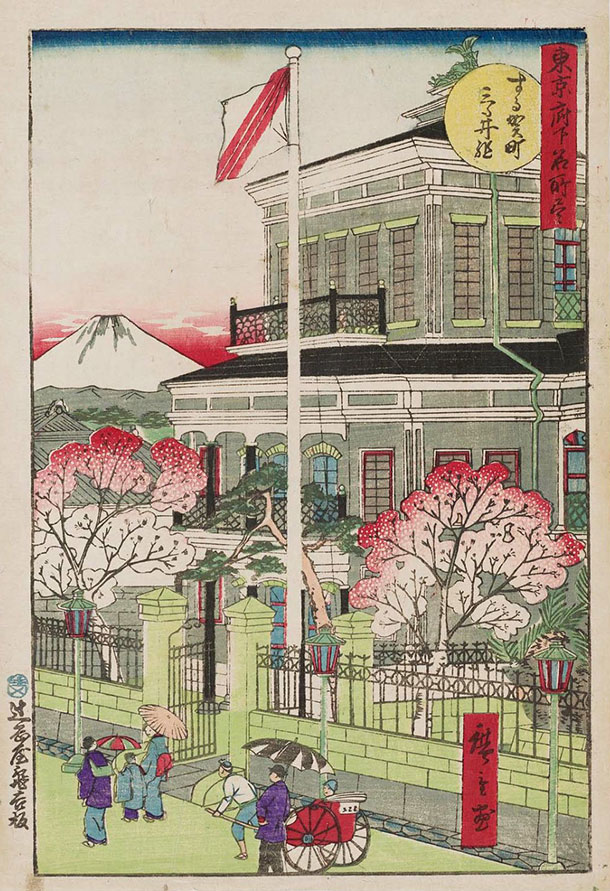

| Utagawa Hiroshige III: Surugachô Mitsui kan (Mitsui Bank Building in Surugachô: する賀町三つ井館) Series: Tokyo fuka meisho zukushi (Enumeration of famous places in Tokyo suburban districts: 東京府下名所尽) Published by Tsujiokaya Kamekichi in 1875 Woodblock print, ôban format (357 x 244 mm) |

Much of Hiroshige III's work was focused on so-called kaika-e (enlightenment pictures: 開化絵), meaning prints that illustrated the popular political mantra of the day, Bunmei kaika ("Revolution in civilization," or "Civilization and enlightenment": 文明開化). Typical subjects — all reflecting the influence of the West — included Japanese architecture (brick buildings), infrastructure (railroads, bridges), and manners and customs (dresses, bowler hats). Mostly, these designs reflected the modernization of early Meiji Japan during the 1870s and 1880s. Of particular importance, scenes of Westernization and new forms of Meiji restoration were admired and sought after. Partly, there was a didactic purpose in publishing such prints, although financial profitability always remained of paramount concern to Hiroshige III and his publishers. Today, kaika-e often prove to be valuable as visualizations of how the Japanese perceived the influence and desirability of adopting Western manners and customs, architecture, and science.

An example of a kaika-e by Hiroshige III is shown above. Titled Surugachô Mitsui kan (Mitsui Bank Building in Surugachô: する賀町三つ井館), it is from the series Tokyo fuka meisho zukushi (Enumeration of famous places in Tokyo suburban districts: 東京府下名所尽) published by Tsujiokaya Kamekichi in 1875. This sheet exemplifies the transitional nature of ukiyo-e design of urban subjects in early Meiji Japan. We have the hybrid elements of pedestrians wearing either conventional Japanese clothes or Western-style fashions. Flowering cherry tress are in full bloom, and majestic Mount Fuji can be seen off in the distance under a sunlit red sky. However, what stands in contrast to these Japanese emblems is the newly constructed Mitsui Bank in Surugachô. Completed in 1874, it combined traditional Japanese woodworking techniques with a Western-style approach to design.

An example of a kaika-e by Hiroshige III is shown above. Titled Surugachô Mitsui kan (Mitsui Bank Building in Surugachô: する賀町三つ井館), it is from the series Tokyo fuka meisho zukushi (Enumeration of famous places in Tokyo suburban districts: 東京府下名所尽) published by Tsujiokaya Kamekichi in 1875. This sheet exemplifies the transitional nature of ukiyo-e design of urban subjects in early Meiji Japan. We have the hybrid elements of pedestrians wearing either conventional Japanese clothes or Western-style fashions. Flowering cherry tress are in full bloom, and majestic Mount Fuji can be seen off in the distance under a sunlit red sky. However, what stands in contrast to these Japanese emblems is the newly constructed Mitsui Bank in Surugachô. Completed in 1874, it combined traditional Japanese woodworking techniques with a Western-style approach to design.

The Kawase Bank Mitsuigumi, completed in 1874, was at the time a new structure in Surugachô, Tokyo (present-day Nihonbashi Muromachi, Tokyo). Shimizu Kisuke II (二代 清水喜助 1815–1881) was the contractor for both the design and construction of the building. He was noted for developing an eclectic quasi-Western style of architecture that blended Western and Japanese architectural styles, realized through the use of traditional Japanese construction techniques. He completed three buildings that presaged the modern architecture of Japan. The Mitsui Bank building in Surugachô was a wooden three-story building with various Western elements. However, it also had a bronze shachihoko (mythical fish with a tiger-like head: 鯱鉾 or 鯱 or 鱐) on the peak of the roof in the most conspicuous place (visible in Hiroshige III's print just to the left of the round yellow title cartouche). Traditional Japanese woodworking techniques were used to build the arch-shaped windows and doorways that graced the building. A period photograph of the bank is also shown immediately above.

|

| Utagawa Hiroshige III: Eitai-bashi (Eitai Bridge: 永代ばし) Series: Tokyo meisho zue (Views of famous places in Tokyo: 東京名勝圖会) Published by Hiranoya Shinzô (Akindô) in 2/1869 Woodblock print, ôban format (360 x 245 mm) |

Early in his career, Hiroshige III produced views that were securely in the mode of his master Hiroshige I's landscapes and city scenes. In the print shown above, we see the Eitai-bashi (Eitai Bridge: 永代ばし) from the series Tokyo meisho zue (Views of famous places in Tokyo: 東京名勝圖会) published by Hiranoya Shinzô (Akindô) in 2/1869. The busy scene is somewhat rigid in its composition that differs from the more lyrical and often more spacious views that we often associate with Hiroshige I. A crowded bridge over the Sumida River was a conventional theme in ukiyo-e prints, illustrated books, and paintings. The Eitai-bashi ("Eternal Bridge," so named as a auspicious wish for the Bakufu government of the Tokugawa clan) was built around in 1698 upon the request of the fifth shôgun, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (徳川綱吉), to celebrate his fiftieth birthday. Spanning the Sumida river, it connected with Fukugawa (深川) and the shrine Tomioka Hachimangû (富岡八幡宮). In 1807, during a festival procession (held every twelve years), a boat belonging to a daimyô (feudal lord: 大名) passed under the bridge, whereupon the warden stopped the crowd from crossing. When the boat passed, hundreds of pedestrians rushed onto the bridge, causing it to collapse near the Fukagawa side where the span broke in two places. It is said that more than 1,400 people fell into the river and drowned. In 1897, the rebuilt wooden bridge was replaced by a structure of iron and steel (the first such bridge construction in Japan), although the wooden piers were retained. The Great Kantô Earthquake of 1923 destroyed that bridge (burning the wooden piers), and finally the Eitai-bashi took the form of its current structure in 1926.

The aforementioned "enlightenment" of Japan during the Meiji period (1868-1912: 明治時代) included the promotion of industry, communication, and commerce through the development of telegraph (1869), telephone (1877), and postal networks (by 1877, the postal system had become a great success and joined the International Postal Union). Japan's modernization also embraced the construction of railways. On July 8, 1853, when American Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into the harbor at Tokyo Bay, he brought with him technological wonders as gifts for the emperor to impress the Japanese with the superior achievements of western culture. Among these was a quarter-size steam engine, complete with 350 feet of 18-inch track.

|

| Ryûsai [Utagawa] Hiroshige III Saikyo Kobe no Aida Tetsudo Kaigyo Shiko shômin haiken no zu (View of Attending the Opening Ceremony of the Kyoto to Kobe Line) Woodblock print, ôban triptych (372 x 745 mm), 1877 |

A rail line between Tokyo and Yokohama was inaugurated on October 14, 1872. In the Kansai region (which includes the cities of Kobe, Osaka, and Kyoto), an early rail transportation system was also established. In May 1874, the line was completed between Osaka and Kobe, and in September 1876, from Osaka to Kyoto. The following year, on February 5th, the through-line opened between Kyoto and Kobe (via Osaka) and the Emperor Meiji made the round trip. He gave his opening speech at Kyoto station, but this print shows the ceremony taking place at Osaka Station, which, incidentally, was not a dead-end terminus station, as Hiroshige III has drawn it in the composition shown here.

Hiroshige III's names

Surname:

Utagawa (歌川)

Personal Names:

Gotô Torakichi (後藤寅吉) childhood name

Andô Tokubei (安藤徳兵衛)

Art names (geimei):

Shigemasa (重政)

Hiroshige (廣重) starting around 1869

Shigetora (重寅)

Possibly Hiromasa (廣政) ?

Pseudonyms (gô):

Isshôsai (一笑齋)

Ryûsai (立齋)

Nickname:

"Meiji" Hiroshige (明治廣重)

Pupils of Hiroshige III

Shôsai Ikkei (昇齋一景 also used Isshôsai 一昇齋 act. c. 1870s)

© 2021 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Marks, Andreas: Japanese woodblock prints: Artist, publishers and masterworks 1680-1900. New York: Tuttle Publishing, 2010.

- Roberts, Laurence: A Dictionary of Japanese Artists: Painting, Sculpture, Ceramics, Prints, Lacquer. Tokyo/New York: Weatherhill, 1976, p. 45.

- Yonemura, Ann: Yokohama: Prints from Nineteenth-Century Japan. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1990, pp. 181-183, 185-189, and plate nos. 78-79, 81-83.

Viewing Japanese Prints |