Isoda Koryûsai (礒田湖龍齋)

|

|

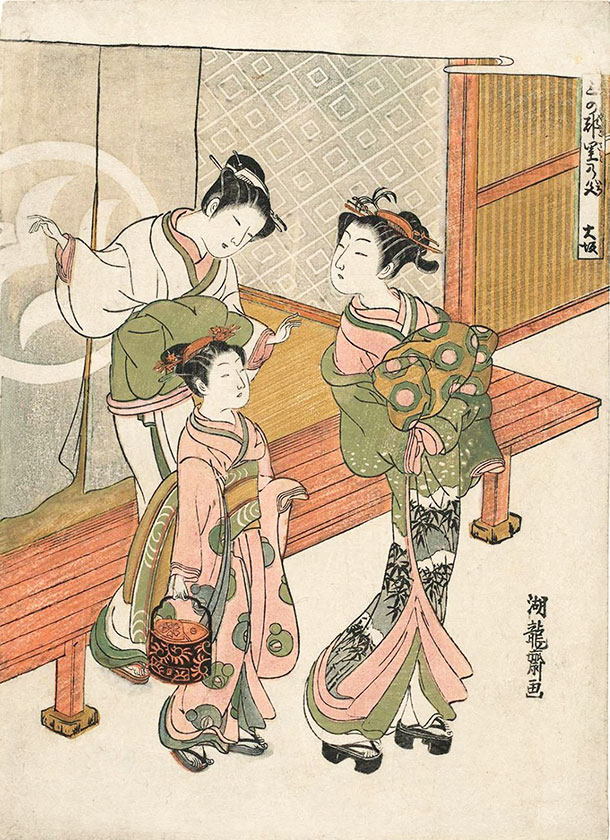

| Isoda Koryûsai: Osaka (大阪) Series: Mitsu no miyako sato no iro ("Pleasure Quarters of the Three Capitals: 三の都里の色) Woodblock print, chûban (270 x 195 mm) |

Isoda Koryûsai (礒田湖龍齋), active c. 1769-90, had a connection with the samurai house of Tsuchiya in Ogaya-chô, perhaps as a retainer, but after his lord's death Koryûsai became a rônin ("wave man," a samurai without a lord or master). He seems to have relinquished his samurai ranking and then moved to the Yagenbori district near the Ryûgoku Bridge in Edo (a few of his signatures bear the prefix Yagenbori inshi, "Recluse of Yagenbori"). Another of his signatures was Koryûsai Haruhiro, used in early works, which suggests a direct, perhaps student-teacher, relationship with the preeminent ukiyo-e master Suzuki Harunobu, who lived nearby in Yonezawa-chô. Even so, while Koryûsai's early works reveal Harunobu's influence, he eventually developed his own style.

The design shown above is from a series of chûban-format prints titled Mitsu no miyako sato no iro (Pleasure Quarters of the three capitals: 三の都里の色). This particular design represents the city of Osaka (大阪). It is an early work by Koryûsai that clearly shows the influence of Harunobu. The courtesan standing on the right is a petite idealization of young womanhood, with that ethereal quality more often associated with Harunobu's creations. Her kamuro (child attendant: 禿) carries a lacquered caddy, while the yarite (brothel madam or supervisor: 遣手) hovers over them. This particular impression is well preserved with only partial fading, most noticeably the blue of the large curtain. The slightly tarnished dark orange (made from tan or red lead: 丹) was a standard colorant most often found in earlier ukiyo-e, but it was much favored by Koryûsai and became something of a "signature" pigment in his work. It was colorfast and so even in prints with significant fading, the red lead pigment often remains nearly unchanged (see also an example by Bunchô).

The design shown above is from a series of chûban-format prints titled Mitsu no miyako sato no iro (Pleasure Quarters of the three capitals: 三の都里の色). This particular design represents the city of Osaka (大阪). It is an early work by Koryûsai that clearly shows the influence of Harunobu. The courtesan standing on the right is a petite idealization of young womanhood, with that ethereal quality more often associated with Harunobu's creations. Her kamuro (child attendant: 禿) carries a lacquered caddy, while the yarite (brothel madam or supervisor: 遣手) hovers over them. This particular impression is well preserved with only partial fading, most noticeably the blue of the large curtain. The slightly tarnished dark orange (made from tan or red lead: 丹) was a standard colorant most often found in earlier ukiyo-e, but it was much favored by Koryûsai and became something of a "signature" pigment in his work. It was colorfast and so even in prints with significant fading, the red lead pigment often remains nearly unchanged (see also an example by Bunchô).

Koryûsai designed prints, paintings, and illustrated woodblock-printed books. His paintings seem to have first appeared in the early 1770s, and along with Utagawa Toyoharu (歌川豊春: c. 1735-1814), he is considered preeminent in bijinga (pictures of beautiful women: 美人画) during the 1770s. Koryûsai's manner of rendering landscape backgrounds in his scrolls and prints suggests that he had training in the Kanô-school (狩野派) academic style of painting.

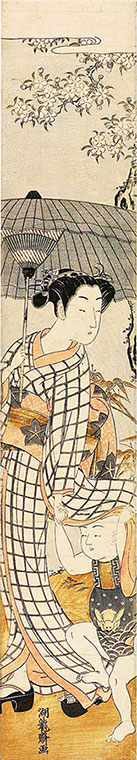

Among Koryûsai's best prints were some kachô-e (bird and flower prints: 花鳥絵) and shunga ("spring pictures" or erotica: 春画; also called makura-e or "pillow pictures": 枕絵). Also notable were various hashira-e ("pillar-prints": 柱絵), arguably some of the best designs ever created in the format. One example, circa early 1770s, is shown on the left (it measures 656 x 117 mm). A young woman carries an umbrella while holding the hand of a boy (presumably, her son) who covers the top of his head with her furisode ("swinging sleeve": 振袖) in order to keep dry. In a restrained but clever manner, Koryûsai has found a way to partly offset the insistent verticality of the tall and narrow hashira format by introducing a curve in the beauty's lower robe, then echoing that curve with the furisode, and accentuating the resulting diagonals with a lattice pattern on the outer robe. Equally important, the charm of the scene is undeniable.

By 1774-75 Koryûsai began to find his way out from under the influence of Harunobu and develop his own style of bijinga (prints of beautiful women: 美人画). He abandoned the winsome, delicate creatures like those above and began introducing women with greater weight and volume. These beauties commanded center stage and more completely filled the pictorial space. (It should be noted that other artists also began to concentrate on larger figures in the ôban format during the mid- to late-1770s, such as Kitao Shigemasa, whose masterpieces in this genre are readily identifiable by their distinctive style.)

Koryûsai's most important body of work in this new manner was the series Hinagata wakana no hatsu moyo (Patterns for New Year fashions, fresh as young leaves: 雛形若菜の初模様), published in the ôban format by Nishimura Yohachi (Eijûdô), with some issued by Watanabe Jûzaburô from about 1776 to 1782. At least 140 ôban designs are known by Koryûsai (plus another eleven added by Torii Kiyonaga); the number of prints suggest that the series was quite popular. The shift from chûban to the larger size helped to establish the ôban as the standard format in ukiyo-e printmaking, and the new ideal of a more ample female figure influenced the next generation of artists, including Kiyonaga. In fact, Kiyonaga, as well as Katsukawa Shunzan, continued this series, also under the direction of the publisher Eijûdô.

The illustration from this important series is shown below. It depicts an ôiran (high-ranking courtesan: 花魁) named Nioteru (にほてる) of the Ôgiya (あふきや) brothel with her two shinzô (teenage attendants, lit. "newly launched" courtesans: 新造) and kamuro (younger girl attendants: 禿) on parade in the Yoshiwara during the sixth month (as identified by the subtitle, minazuki, 水無月). Nioteru and her kamuro wear similar black robes patterned with breaking waves, while one of Nioteru's underrobes has a design with the character kotobuki (meaning "long life" as well as "congratulations": 壽). The increased size provided by the ôban sheet is matched by the greater volume and mass of the figures, compared with Koryûsai's earlier, Harunobu-like waifs. The arrangement of the women is notable, with the attendants walking in a circular constellation around their mistress. In prints such as this, Koryûsai dramatically separated himself from Harunobu's fragile idealizations and introduced greater realism in his portrayal of the women of the pleasure quarters.

|

| Isoda Koryûsai: The ôiran Nioteru (にほてる) of the Ôgiya (あふきや) with her attendants Series: Hinagata wakana no hatsu moyo (Patterns for New Year fashions, fresh as young leaves: 雛形若菜の初模様) Woodblock print, ôban (387 x 259 mm) |

It appears that Koryûsai abandoned printmaking around 1780 to concentrate exclusively on painting, another genre in which he excelled. It is known that in 1782, he was awarded the title of hokkyô (literally "bridge of the law": 法橋), an honorary ranking that since the Nara period (710-784) had been given to priests, although by the Edo period (1603-1868) the title was also extended to artists and artisans. All-told, Koryûsai designed over 2,500 prints, possibly making him the most prolific designer of single-sheet prints in eighteenth-century Japan. © 2001-2021 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Brea, L. and Kondo, E.: Ukiyo-e Prints and Paintings: From the Early Masters to Shunshô. Genoa: Edoardo Chiossone Civic Museum of Oriental Art, 1980, pp. 170-213.

- Clark, T.: Ukiyo-e Paintings in the British Museum. London: British Museum Press, 1992, p. 104.

- Gentles, M.: The Clarence Buckingham Collection of Japanese Prints: Volume II. Art Institute of Chicago, 1965, pp. 181-274.

- Hockley, A.: The Prints of Isoda Koryûsai: Floating World Culture and Its Consumers in Eighteenth-Century Japan. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003.

Viewing Japanese Prints |