Tôshûsai Sharaku (東洲齋写楽)Tôshûsai Sharaku (東洲齋写楽), active c. 1794-95, was one of art history’s most fascinating and mysterious figures. He produced an astonishing body of work in a very brief working period, from the fifth month of 1794 to the first month of 1795 (totaling 10 months due to an intercalary month). The number of works was also small, although the reported count varies depending on whether one considers certain polyptychs as single compositions or as separate sheets and, indeed, which sheets belong together as one design. If we simplify and count each sheet separately, the total would be 145 known individual sheets. The following table presents Sharaku's prints in chronologically arranged groups.

There are also 18 known drawings attributed to or by Sharaku: 10 double portraits of sumo wrestlers (9 lost in the 1923 Kantô earthquake, 1 surviving in the former Henri Vever collection), and 8 drawings of actors in the 8th month, 1794 (these were mitate of unstaged performances).

Sharaku's Identity Indeed, a Nô actor named Saitô Jûrôbei is named in a later Nô program of 1816, so we know that such an actor existed. Also, the Lord of Awa arrived in Edo on 4/6/1793, then was absent from 4/21/1794 through 4/2/1796, possibly indicating that if Sharaku (i.e., the Nô actor Jûrôbei) was not obliged to accompany his lord, he would have been free to explore his printmaking during the period when Sharaku's prints appeared. In addition, Sharaku might have been trained in Osaka, as his style of drawing was closer to the Osaka master Ryûkôsai than to any Edo artist of the period, and Ryûkôsai's actor portraits in hosoban format preceded Sharaku's working period by about 3 years. Also, some of Sharaku's portraits were of Osaka actors performing in Edo, perhaps an indication of his special interest in these particular entertainers. Overall, the evidence for an Osaka connection is only circumstantial, but it is nevertheless consistent chronologically and plausible stylistically. All the other theories lack convincing corroborating evidence (these include claims that Sharaku was, among others, the artist Hokusai, Toyokuni, Kiyomasa, or Utamaro; the publisher Tsutaya Jûzaburô; the haiku poet Sharaku residing in Nara and appearing in manuscripts from 1776 and 1794; and a certain Katayama Sharaku, the husband of a disciple named Nami at the Shintô headquarters at the Konkô-kyô, who was said to have resided at Tenma Itabashi-chô, Osaka). Sharaku's Disappearance If Sharaku did not quit printmaking simply because his prints failed to sell, perhaps there were other contributing circumstances that forced him to abandon print design. If Sharaku was indeed Saitô Jûrôbei, did he have commitments to his Nô troupe or to his lord that forced an abrupt end to his printmaking career? What effect, if any, did patronage have on Sharaku's disappearance? If he had private means or sponsorship, what role did it play in his choice of style, plays, and actors, or did the initial support for Sharaku's unconventional portraiture run its course rather quickly? Could disappointing print sales have led his publisher, Tsutaya Jûzaburô, to withdraw the encouragement or support Sharaku needed to continue? It is interesting to note that Sharaku's later designs relied more and more on compositions not directly related to actual stage performances (a genre called mitate), with actors in roles they did not perform for the given plays. One theory suggests that this trend indicates Sharaku faced increasingly limited access to the theater and its actors (for reasons unknown). Consequently, so the theory goes, by producing too many portraits that did not satisfy theater fans, his prints failed to sell.

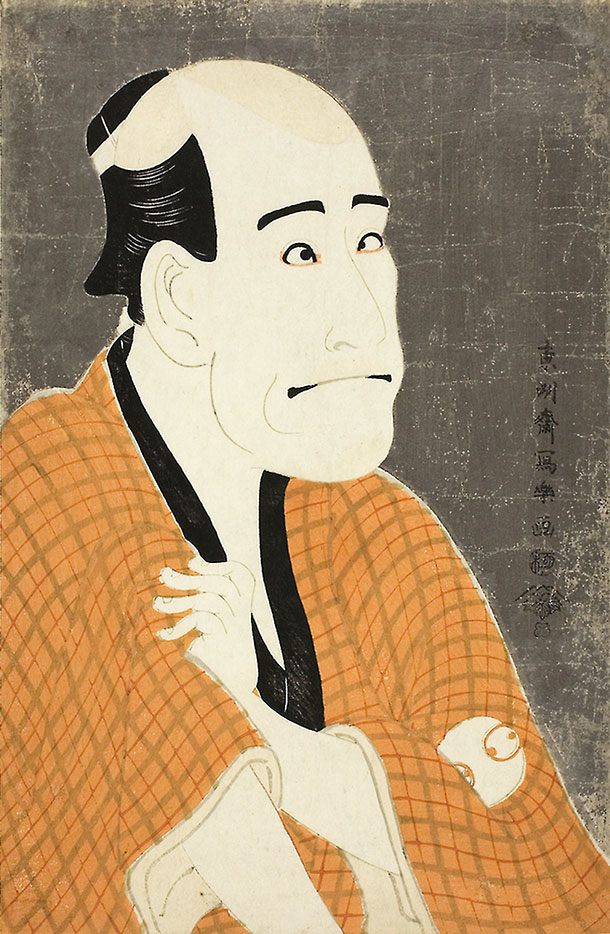

Sharaku's Artistic Style If we examine the illustration at the top of this page, we see the actor Arashi Ryûzô II (嵐龍蔵) as Ishibe Kinkichi (石部金吉) from the play "Blooming Iris, Soga of the Bunroku Era" (Hana-ayame Bunroku Soga: 花菖蒲文禄曽我) performed at the Miyako Theater, 5/1794. This was a popular vendetta play in which the Soga brothers attempted to avenge their father's murder of 20 years earlier. Kinkichi was a mean-spirited money lender (in one scene he kicks and beats up a character named Bunzô, and his crude demeanor and grimacing mouth seem to suggest something of his venal character. We can also observe Sharaku's use of bold, thick lines for the eyes, eyebrows, and mouth, in contrast to the thin, delicate lines of the remainder of the face. Sharaku's artistic style was one in which true expressiveness was revealed by both the stage persona and the actor himself. Perhaps Sharaku intended to concentrate on or even exaggerate the expressive possibilities of the eyes and mouth, key aspects of physiognomy used to great effect by kabuki actors in their mie ("displays" 見得 or static poses at climactic moments in the plays). Sharaku's use of mica backgrounds, although not original to him, might also have served as devices meant to mimic reflected visages in mirrors and thus suggest a level of realism as if a true likeness (nigao, 似顔 or kaonise, 顔似せ) of the actor was reflected back at the observer. His mica-ground portraits served as images of a confluent physical and emotional reality to far greater degree than did the actor portraits of earlier ukiyo-e artists. Sharaku's Onnagata The illustration shown immediately above is a portrait of the supreme onnagata Segawa Kikunojô III (1751-1810) as the Tsuma (wife) Oshizu (妻おしず), spouse of a minor character named Tanabe Bunzô (田辺文蔵), also in "Blooming Iris, Soga of the Bunroku Era" (Hana-ayame Bunroku Soga: 花菖蒲文禄曽我) at the Miyako Theater, 5/1794 (discussed earlier). Oshizu's husband was a stalwart supporter of the Soga brothers vendetta. Sharaku designed eleven prints for this performance, and the portrait of Oshizu is one of the best. It is extraordinary that a somewhat overweight, middle-aged man could bring such female characters to life in such a convincing manner. Yet Kikunojô did indeed do this, specializing in ingenues and courtesans. He was ranked the best actor in female roles in Edo in 1782, and by 1790 he commanded the huge annual salary of 1,850 ryô. Kikunojô's nickname included the title of a Shintô deity (Daimyôjin), and there was even a makeup named after him. He was still at the height of his fame when depicted in Sharaku's print. Afterwards, in 1808, he was made zagashira ("troupe head"), the highest ranking position in a theater company and very rare for an onnagata to achieve.

In the same month and year as the preceding two portraits, Sharaku depicted the actor Osagawa Tsuneyo II (小佐川常世の) as Ippei's older sister (ane) Osan (一平姉おさん) in the play "The beloved wife's multicolored rope" (Koi nyôbô somewake tazuna: 恋女房染分手綱) at the Kawarazaki Theater, Edo in 5/1794. In this remarkable likeness, Tsuneyo II (1753-1808) is shown in one of the many onnagata characters he performed during his career — the role-type (yakugara: 役柄) for which he was most admired. At his height of acclaim, Tsuneyo was ranked "Meritorious - superior - superior - excellent" (kô-jô-jô-kichi: 功上上吉) in Edo actor critiques (yakusha hyôbanki: 役者評判記). Sharaku's print captures brilliantly the male actor who has transformed himself into a female presence on stage. In Sharaku's portraits we do not see an idealization of an actor's physicality, either to conform to the exalted status of particular superstars or to the female roles in which they perform. Underneath expressions of femininity and poise are the real-life, flesh-and-blood men. Perhaps if Sharaku's portraits were indeed too truthful for his contemporaries, it might have been his onnagata ôkubi-e that tipped the balance against his being generally popular. Today, however, these designs are the most sought after and widely admired among the masterpieces of ukiyo-e printmaking. © 2001-2021 by John Fiorillo BIBLIOGRAPHY

|

Viewing Japanese Prints |