YOSHIDA Hodaka (吉田穂高)

|

Yoshida Hodaka (吉田穂高) was born in Tokyo, the second son of Yoshida Hiroshi (1896-1950) and brother of the print artist Yoshida Tôshi (吉田遠志 1911-1995). His mother, Yoshida Fujio (吉田ふじを 1887-1987) was also a an accomplished painter and printmaker, as was his wife, Yoshida [Inoue] Chizuko (吉田千鶴子 1924-2017). Over the course of his career, Hodaka created oil paintings, woodcuts, screenprints, lithographs, mixed-media prints (including especially combining woodcut with photo-etching), collages (including printing shapes with stone, wood, and cardboard), monoprints, stone-carved sculptures, and metal sculptures. He was also an accomplished photographer.

Yoshida Hodaka (吉田穂高) was born in Tokyo, the second son of Yoshida Hiroshi (1896-1950) and brother of the print artist Yoshida Tôshi (吉田遠志 1911-1995). His mother, Yoshida Fujio (吉田ふじを 1887-1987) was also a an accomplished painter and printmaker, as was his wife, Yoshida [Inoue] Chizuko (吉田千鶴子 1924-2017). Over the course of his career, Hodaka created oil paintings, woodcuts, screenprints, lithographs, mixed-media prints (including especially combining woodcut with photo-etching), collages (including printing shapes with stone, wood, and cardboard), monoprints, stone-carved sculptures, and metal sculptures. He was also an accomplished photographer.

Hodaka's family expected him to have a career in science, and so his father Hiroshi neither taught him printmaking nor encouraged him in that direction. In 1944 Hodaka entered the science program in Tokyo's Dai-ichi Higher School, but it was cut short by the allied bombing during World War II. Meanwhile, by early 1945, Hodaka had already taught himself, clandestinely, how to paint with oils, experimenting with abstract designs.

After about four years, Hodaka submitted an oil painting to the Pacific Painting Society, where it won a prize. His father, finally learning of his son's interest in abstract art when he was asked to present the award, remained silent and never accepted Hodaka's commitment to modern art.

In 1948 Hodaka entered an abstract oil in the Second Japan Independent Exhibition, where it received good reviews. From then on, he submitted paintings to avant garde exhibitions in Tokyo. This continued until 1953. Meanwhile, starting in 1950, Hodaka found the woodblock medium more to his liking. He had taught himself how to carve and print woodblocks and began devoting himself to printmaking. Not long after, he was invited to join the prestigious Nihon Hanga Kyôkai (Japan Print Association: 日本版画協会) in 1952.

During their honeymoon in 1953, Hodaka and Chizuko visited the famous garden at the Katsura Imperial Villa. It was a profound experience for Hodaka, who began to see objects and the space around them in different ways. This led to a sense of greater freedom and access to deeper feelings to be expressed in his art. He visited Mexico in 1955 with his brother Tôshi where they saw Mayan artifacts, architecture, and pyramids. Again, the experience was intense for Hodaka, and when he followed up with a trip around the world in 1957-1958, he continued to respond enthusiastically to primitive artifacts in ethnographic museums. He came to believe that "raw life" among primitive peoples exemplified a "magic impulse" as an essential element in their artistic creativity.

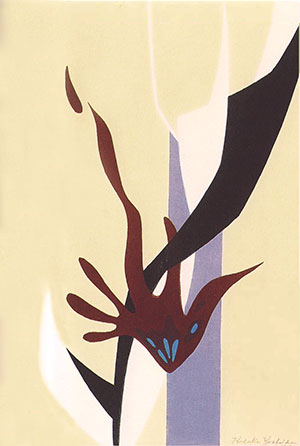

Eugene Skibbe (see ref. below) has proposed that Hodaka went through five main creative periods and three developmental stages. The earliest phase, from 1950/51 to 1953, focused on forms with a simplified, semi-abstract style, often dispensing with adherence to Western-style perspective or depth of field. In the example shown below left, titled "Black flower" from 1952, simplified forms overlap in a modernist nature study. The dark red blossom seems to float above and entwine with the black leaf while other shapes give the composition balance and added interest. Although the colors are not like those of Henri Matisse (1869-1954), the arrangement of forms might suggest Hodaka's familiarity with the late cut-outs of the French master.

|

|

| Yoshida Hodaka: Black flower, 1952 Woodcut Image: 374 x 225 mm; paper: 406 x 278 mm |

Yoshida Hodaka: Hakuhô butsu (Hakuhô Buddha: 白鳳仏), 1954 Woodcut, image: 375 x 225 mm |

Hodaka's second phase, around 1953-1954, was characterized by Buddhist-inspired compositions. The example shown above right is titled Hakuhô Buddha (白鳳仏), which refers to the period 673-686 AD (a non-nengô span of years), used primarily in discussions of architecture, sculpture, and painting. It may also relate to a wider range of years, such as 645-710 AD. Hodaka's design is sometimes called "Buddhist statues." The ambiguity of the semi-abstracted forms has led to more than one interpretation. One source (see Jenkins ref. below) reads the design as a standing Buddha (in black) with his drapery (in brown) arranged in an abstract manner. Skibbe, on the other hand, sees it as more than one statue, which when read from right to left, shows an unfinished sculpted statue in brown, a completed statue in black, and a "spectral" figure left of center. What he called "white ribbon shapes" seem to suggest movement, and the multiple perspectives derive from Hodaka's experience when viewing the spatial arrangements of the garden at Katsura.

Other works during Hodaka's second creative phase range from realistic to partly abstract to entirely abstract. One example of Hodaka's naturalistic manner is shown below. Clearly, just as it was for his brother Tôshi, Hodaka was strongly influenced by their father Hiroshi's style, although with somewhat less complexity in printing technique. Here, the approach is very close to Tôshi's, although the leaves in the trees are rendered in so stylized a manner as to edge toward abstraction. The subject is the Sangatsu-dô (三月堂 also called Hokke-dô, or "Lotus Hall": 法華堂) in Nara, the oldest building (said to have been built between 740 and 747) in the Tôdaiji Temple (東大寺) precinct. Hodaka's design is from a series titled Nihon no Furudera (Old temples of Japan: 日本の古寺).

|

| Yoshida Hodaka: Sangatsu-dô (Hokke-dô), Nara, 1954 Series: Nihon no Furudera (Old temples of Japan: 日本の古寺) Woodblock print, image: 403 x 275 mm; paper: 377 x 250 mm |

Hodaka's third creative phase, which lasted from 1955 to 1963, followed upon his sojourn through Mexico in 1955. At that time he found a new graphic language to express his responses to Mayan art. In particular, he was inspired by the friezes of deities and heroic figures. He devised visually impressive anthropomorphic forms that recall those pre-Columbian bas-reliefs while exploring aspects of mystery, power, magic, movement, and mass in combinations that yielded memorable images. Hodaka was once quoted as saying, "Primitive art ... and the rhythm of life that is seen in it, challenges us. It is the life force (seimei ryoku: 生命力) of the primitive. There is an absolute in human existence that defies the flow of civilization" (see Chiba ref. below).

In the print shown below left, two geometrical but human-like figures face each other. Titled "Ancient people" from 1956, it is apparently intended to represent contrasting male and female forms. The powerful, massive combination of stacked stone-carved forms on the left approaches or leans toward the more diminutive figure on the right. The depiction may imply an ancient narrative involving primitive aspects of human behavior. The "comma" located at the apex of the figure on the right was a familiar form in Hodaka's oeuvre during the third period. He claimed that he saw it as the aforementioned "life force."

Following along a similar theme, Hodaka used Mayan-inspired shapes in another design from 1956, titled "Masks," shown below right. Circles appear in three places. The dark-gray "mask" in the upper section can be read as a frontal or a profile view of a face or mask. The brown textured form on the right suggests stonework into which several forms have been chiseled. The overall effect is one of primeval magic communicated by a primitive culture.

|

|

| Yoshida Hodaka: Ancient people, 1956 Woodcut; paper: 515 x 416 mm |

Yoshida Hodaka: Masks (面), 1956 Woodcut, paper: 575 x 421 mm |

The influence of Mayan and Aztec culture continued to appear in Hodaka's works from the early 1960s, although it was often diffuse and fully assimilated into abstraction. When combined with his experiments in collage and monoprint transferred to woodcuts, the result was a kind of totemic vertical arrangement of shapes and colors. In the example shown at the top of this page, an artist proof titled "Cause, Yellow" from 1962 (image: 749 x 375 mm), lines and circular and comma forms are overlayed against a massive, textured, stone-like background. The stasis in the lower half is offset by movement and energy in the upper section of the design.

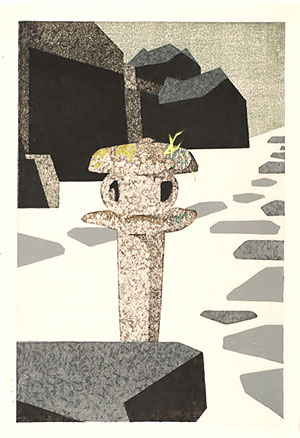

During Hodaka's third phase, he also produced designs of traditional Japanese scenes. However, these works featured simplified shapes enhanced by printing techniques that described textured surfaces. In Ishidôrô (Stone lantern: 石灯籠), shown below left, the lantern is located in the foreground; behind it is a nobedan (pathway of cut stones: 延段) and buildings outlined in simple geometrical forms that are filled in with solid blacks and textured grays. A similar approach to a conventional Japanese subject, although in a larger format (578 x 419 mm), is shown below right. Titled Chashitsu (Tea House: 茶室), the nobedan angles its way toward the entrance with dramatic receding depth. Again, all forms are reduced to essentials, providing just enough information for the observer to decipher the scene, but leaving out substantial detail to create a timeless view of a "sculpted" landscape.

|

_300w.jpg) |

| Yoshida Hodaka: Ishidôrô (Stone lantern: 石灯籠), 1956 Woodcut; paper: 368 x 241 mm |

Yoshida Hodaka: Chashitsu (Tea House: 茶室), 1956 Woodcut, paper: 578 x 419 mm |

In the next major phase, spanning 1966 to 1972, Hodaka began to incorporate some of the ideas espoused in Pop Art and modern commercial culture. Skibbe describes this approach as Hodaka assimilating the trends found in mass consumerism whereby "modern mass-media images became the next 'primitive' artifact to arouse Hodaka's curiosity." Many of these works include the word shinwa (myth or mythology: 神话) in their titles, designating them as contemporary works that contain within them fundamental truths just as "magical" as those found in ancient mythological stories. Some of the compositions include collage-like arrangements, but instead of imitating assembled forms from various materials, Hodaka cut images out of magazines and books, reduced them to fragments, and fitted them together as actual collages. He then photographed the collage and used photo-etched zinc plates inked with black for the details while adding colors printed from woodblocks.

In the example below, titled "Mini Mythology" from circa 1966, Hodaka set up his composition in the form of a triptych. The contemporary "mythological" elements include cropped human figures, a wristwatch, a passenger jet in flight, a mirror, a towed car, a playing card, an urban edifice, fragments of clothing, a fragment of paper currency, and ruled parallel horizontal and vertical lines. The effect is not unlike a grouping of objects found in an anthropological excavation, but in this instance, the theme may well be the chaos of modern life.

|

| Yoshida Hodaka: "Mini Mythology," 1966 Color woodblock and photo-screenprint; edition: 85; image: 330 x 475 mm |

Unusual landscape prints came to define Hodaka's next phase (1970-1973), which overlapped the prior period. He again found inspiration in Pop Art and everyday life, and continued to rely on collage techniques, photography, etching, and colors from woodblocks. The print shown below left, titled "Landscape C-B" from 1971, seems to express a troubling relationship between humans and the natural world. The upper two-thirds of the composition present a relining female in yellow, her head and a single eye barely visible along with her right arm below a beige sky. Her form appears as if it were a part of a landscape, perhaps suggesting the impact of humankind on the earth. In the lower third, two more female forms are shown: the head of a woman colored in lavender in the black area at the lower left, and a partial view of a woman in orange-yellow reclining along the bottom edge of the print, again with only a single eye visible. Linear and curved lines add an abstract dimension, while photo-etched passages of a city scene (lower left corner) and flowers (lower right corner) further establish the natural world in competition with the humankind.

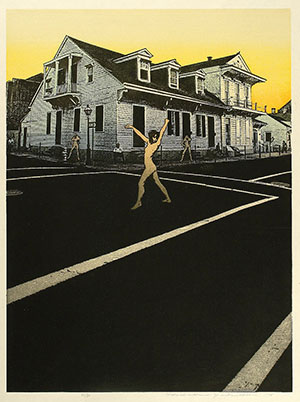

Following the landscape prints, Hodaka introduced a series of designs with seductive young women, most often provocative nudes, placed in front of old houses. This phase lasted from about 1974 to 1979. Hodaka was interested in representing modernity in conflict with tradition, as well as the complex impulses in human nature. He used the collage method again, cutting out the houses from his own photographs, and the female figures from magazines. In the print shown below, titled "Sakuhin ("Work": 作品)" from 1976, three nudes appear before a large old house. The foremost figure strikes a dance pose while standing in the middle of a wide street.

|

|

| Yoshida Hodaka: "Landscape C-B," 1971 Photo-etching and color woodblock Edition: 75; Paper: 460 x 350 mm |

Yoshida Hodaka: Sakuhin ("Work": 作品) Photo-etching and color woodblock Edition: 60; paper: 538 x 410 mm |

From 1979 to 1985, Hodaka removed the nude figures from his compositions while continuing to present images of old houses taken from his photography. The first design known in this mode is "From My Collection - White House" (Watakushi no corekushon yori - shiroi ie) a large-format work from 1979. The house is one photographed by Hodaka in Nicaragua. Unusually, instead of combining woodcut and photo-etching, he recarved the image entirely in woodblocks. The explicit presence of humans is gone now, although the rocking chair at the doorway suggests unseen inhabitants within the house. The shift here from the prior style of houses with nudes is toward a focus on inanimate structures constructed by humans and therefore valid as evocative "primitive" objects in their own right.

|

| Yoshida Hodaka: Watakushi no corekushon yori - shiroi ie (From My Collection - White House), Woodblock; edition: 100; image: 500 x 635 mm |

In a similar vein, Hodaka produced a series of wall and door prints that expressed his responses to weathered and worn objects. His treatment resulted in views that spoke of monuments whose marks and damages hinted at legible messages or glyphs left behind by the people who built and used the objects. In the example shown below left, titled "Green Wall, H.M." created in 1982, Hodaka used a photograph that he had taken in Huejotzingo, Mexico in 1981. The wall was a section of an old house reused in a newly constructed home. This wall must have had, for Hodaka, a symbolic resonance suggesting a mysterious power or magic, much like the effect that Mayan artifacts and architecture had on him when he first explored the theme in printmaking in the mid 1950s.

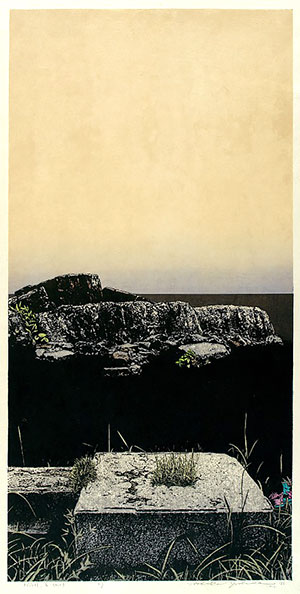

Hodaka modified this singular approach for one of his largest prints: "Promontory" (Object, stone — Hiroshima B) from 1988. The message here is obvious: a wasteland with a baren landscape and concrete foundation for what was once a building or home poses a dire warning about the devastation humans are wreaking upon the natural and constructed worlds.

|

|

| Yoshida Hodaka: "Green Wall, H.M.," 1982 Photo-etching and color woodblock Ed.: 50; Image: 677 x 508 mm; Paper: 725 x 548 mm |

Yoshida Hodaka: Promontory ("Object - Stone"), 1988 Photo-etching and color woodblock Image: 840 x 420 mm; paper: 900 x 480 mm |

During his career, Yoshida Hodaka participated in many exhibitions, winning a prize at the Lugano International Print Bienniale in 1962, and another at the Seoul International Print Bienniale in 1972. He was given a solo show at the Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts, Tokyo in 1988. He received, posthumously, from the emperor, the Fourth Order of the Rising Sun Medal in 1995.

Yoshida Hodaka's works are held in many private and public institutions around the world, including the Art Institute of Chicago; British Museum, London; Brooklyn Museum, NY; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Cincinnati Art Museum; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Hiroshima Contemporary Art Museum: Harvard Art Museum; Honolulu Academy of Arts; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts, Tokyo; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama; National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; New York Museum of Modern Art; Smithsonian Institution; Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas; Tokyo Metropolitan Museum; Yale University Art Gallery. © 2020 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Catalogue of Collections [Modern Prints]: The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (Tokyo kokuritsu kindai bijutsukan shozô-hin mokuroku, 東京国立近代美術館所蔵品目録). 1993, pp. 263-265, nos. 2540-2560.

- Chiba, Hiroko and Ota, Pauline: Abstract Traditions: Postwar Japanese Prints from the DePauw University Permanent Art Collection. Greencastle, Indiana: DePauw University, 2016, pp. 80-81.

- Jenkins, Donald: Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century. Oregon: Portland Art Museum, 1983, p. 136, no. 118.

- Skibbe, Eugene: "Yoshida Hodaka: Magic, Artifact, and Art," in: Allen, Laura, et al.: A Japanese Legacy: Four Generations of Yoshida Family Artists. Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2002, pp. 109-149.

Viewing Japanese Prints |