KOMAI Tetsurô (駒井哲郎)

|

Komai Tetsurô (駒井哲郎), born in Nihonbashi, Tokyo in 1920, was the sixth son in a family living near and supplying ice for fish markets. He learned the basic techniques of copper-plate etching while still in Keio High School (grad. 1938) after encountering examples in the magazine Etchingu ("Etching": エッチング) published by Nishida Takeo (西田武雄 1894-1961). He said, "I entered the art world when I started making copper-plate prints, without first doing any other drawing or painting." Around this time, in 1934-35, he joined Nishida's Etchingu Kenkyûsho (Etching Institute) where he began learning copperplate printing techniques. In a gallery near the institute's laboratory he saw intaglio prints by Western artists such as Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), Charles Meryon (1821-1868), James Whistler (1834-1903), Odilon Redon (1840-1916), and Edvard Munch (1863-1944), as well as works by Hasegawa Kiyoshi (長谷川潔 1891-1980), who spent much of his life in France.

|

| Komai Tetsurô: Tsuka no ma no gen'ei ("Momentary Illusion": 束の間の幻影) Etching and [coarse-grain] sandpaper, 1950 (185 x 280 mm) Sandopêpâ ni yoru etchingu (サンドペーパーによるエッチング) (Awarded special-section "Japanese in São Paulo Prize" at the First São Paulo Biennale in 1951) |

Komai next attended the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (Tokyo Bijutsu Gakkô: 東京美術学校), now called Tokyo Geijutsu Daigaku (Tokyo University of the Arts, 東京藝術大学) as a student in the department of oil painting (grad. 1942). That same year, Komai entered a special French course at the Tokyo School of Foreign Languages (Tokyo Gaikokugo Gakkô: 東京外国語学校, today called Tokyo Gaikokugo Daigaku, the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies: 東京外国語大学), graduating in 1943. A little more than a decade later, he traveled to France in April 1954, remaining there until November 1955, where he quickly sought out Hasegawa Kiyoshi and took his advice to enroll in special workshops in burin (engraving) technique taught by Robert Camis at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Unfortunately, Komai's stay in Paris did not go well, as he seems to have reacted to the formidable tradition of printmaking in France by suffering a loss of confidence, and so he produced very little. Komai ultimately broke the spell of despair after his return to Japan by providing, in 1957, the monochrome etching titled Jumoku rudon no sobyô ni yoru (Tree — After a Sketch by Redon: 樹木 ルドンの素描による) as a frontispiece for a book of poems by Ôyama Masataka (小山正孝 1916-2002). Komai had a profound esteem for Redon's work, who in Komai’s words, “in his later years created a world of brilliant color in oil paint and pastel.”

In 1943, Komai joined MHS Planners, Architects & Engineers Ltd. (i.e., the prestigious Matsuda-Hirata-Sekkei architectural firm with roots going back to 1929). This work was interrupted by his serving as a army infantry private in World War II. After the war, Komai returned to MHS while continuing to work on copper-plate printmaking. In 1947 he joined the Ichimokugai (First Thursday Society: 一木会), the loosely knit group of sôsaku hanga ("creative print": 創作版画) artists led by Onchi Kôshirô. Komai was inspired by Onchi, as were so many other young print artists, to follow his own experimental path in printmaking. (Many years later, in 1975, Komai designed an aquatint in homage to Onchi.) He also contributed to the last two portfolios of prints produced by all the members of the society (the Ichimokushû portfolios V and VI, 1949 and 1950). In 1948 Komai submitted works to the Sixteenth Annual Japan Print Association Exhibition, winning a prize. He also became a member of that association (Nihon Hanga Kyôkai: 日本版画協会). Another prize followed in 1950 for his mezzotint and softground etching titled Kodoku na garasu (Lonely Crow: 孤独な烏 etched in 1948) at Twenty-Seventh Annual Exhibition of the Spring Principle Association (Shun'yôkai: 春陽会), an organization that promoted Western-style art in Japan. This apparently was the first year that the association opened its exhibition to prints (oil painting had been its earlier focus). Komai went on to receive various awards throughout his career.

|

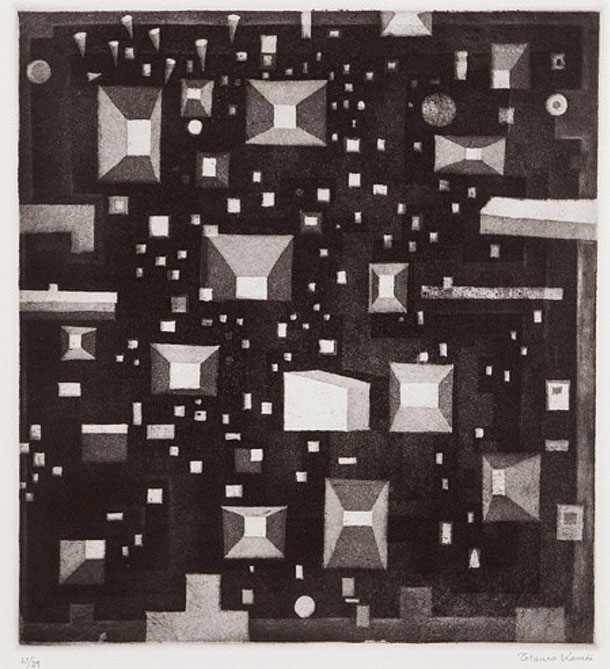

| Komai Tetsurô: Tsuka no ma no gen'ei ("Labyrinth of Time (B)": 時間の迷路B) Etching with aquatint [coarse-grain] sandpaper Akuachinto sandopêpâ ni yoru etchingu (アクアチント・サンドペーパーによるエッチング) 1952, Ed: 27 (232 x 212 mm) (Exhibited at the Salon de Mai, Paris, May 1952) |

Komai has long been recognized as a pioneer in copperplate printmaking in Japan. He is said to have boasted about an unrivaled etching technique using a more highly corrosive solution than was typical with nitric-acid baths. This was at a time when not enough was known about the harmful effects of mismanaged nitric acid fumes as used in printmaking, and so some critics have speculated that spending so many years in toxic environments might have contributed to Komai's relatively early death at the age of fifty-six. His earliest surviving work appears to be Kashi ("Riverbank": 河岸) from 1935, completed when he was only fifteen years of age. This print later won a prize at the Fourth Bunten exhibition in 1941 sponsored by the Ministry of Education, that is, the Bijutsu Shinsa Inkai or Fine Art Reviewing Committee, which began the Bunten exhibitions in 1907, and then reorganized as the Imperial Art Academy (Teikoku Geijutsu-in: 帝国芸術院) in 1937.

|

| Komai Tetsurô: Jikan no gangu (Yellow House: 黄色い家) Dipuetchingu akuachinto (Deep etching and aquatint: ディープエッチング・アクアチント) in colors Edition: 30, 1960 (image: 207 × 146 mm) |

The groundbreaking moment in Komai's career came, however, in 1951 when his etching and coarse-grain print (created in 1950) titled Tsuka no ma no gen'ei ("Momentary Illusion": 束の間の幻影) was awarded a special-section "Japanese in São Paulo Prize" at the First São Paulo Biennale in 1951 (see image at the top of this page). This award from an international competition that was open to all visual arts, along with another award in the same category given to Saitô Kiyoshi, sent shock waves through the Japanese art world, where traditionalists considered printmaking an inferior art form and could scarcely believe that prints, rather than paintings or sculpture, should have received such recognition. This honor was followed by the International Second Winner Award given to Komai at the Lugano International Print Biennale in 1952.

Komai participated in Sekino Jun'ichirô's so-called "copper-plate research group" when, in 1951, Sekino set up an etching press in the kitchen of his home. (Sekino and Komai probably first met at the aforementioned Nishida Etchingu Kenkyûsho.) Sekino taught intaglio printmaking to students and invited fellow artists to experiment, including Hamada Chimei (浜田知明 1917-2018), Hamaguchi Yôzô (浜口陽三 1909-2000), Kobayashi Donge (小林ドンゲ born 1926), and Komai Tetsurô. Two years later, in 1953, the professionals in the group established the Japanese Copper-plate Print Association (Nihon Dôbanga Kyôkai: 日本銅版画協会), with Sekino as its leader and Komai as an eminent member. Also in 1953 (January), Komai had his first solo exhibition, which was held at the Shiseidô Gallery (資生堂) in the Ginza district.

Komai pursued a range of innovative approaches to his art. In 1952 he joined the "Experimental Workshop" (Jikken Kôbô: 実験工房), an exceptionally diverse multi-media avant garde studio whose members from various creative disciplines gathered around the well-known poet, surrealist artist, sculptor, art theorist, spiritual advisor, and art critic Takiguchi Shûzô (瀧口修造 1903-1979). Connecting with literary and poetic figures and groups, Komai also collaborated on many illustrated poetry anthologies and literary publications, which included providing designs for book covers. These projects continued throughout his career and proved to be important creative outlets. Among others, he worked with the poets Ôoka Makoto (大岡信 1931-2017) and Andô Tsuguo (安東次男 1919-2002). In the realm of music, Komai collaborated, for example, with the contemporary classical composer Yuasa Jôji (湯浅譲二 born 1929), a four-time winner of the prestigious Otaka Prize for outstanding orchestral pieces. They produced an experimental audiovisual work for image slide-projection with taped musical accompaniment. It was presented at the Fifth Jikken Kôbô Exhibition on September 30, 1953 as "Lespugue, from a poem by R. Ganzo" (Resupûgû R. Ganzo no tame no shi ni yoru). The experiment made use of new audiovisual device technology called ôtosuraido (autoslide: オートスライド) — an automatic slide projector synchronized with a magnetic audio tape. Komai provided the visual material for the slides while Yuasa composed a piece for flute and piano, recording it in reversed playback mode.

|

| Komai Tetsurô: Jikan no gangu ("Time for toys": 時間の玩具) Akuachinto (Aquatint: アクアチント) in colors, edition: 30, 1970 (image: 385 x 230 mm) |

Although Komai is best known for his exploration of shiro to kuro no sekai (the "world of black and white": 白と黒の世界), he also produced some fine shikisai dôbanga (copper-plate color prints: 色彩銅版画). Examples date from at least as early as 1953. One widely admired design from 1960 is Komai's Kiiroi Ie (Yellow house: 黄色い家), shown earlier on this page. The technique for this small-format work (207 × 146 mm) featured deep etching and color aquatint. In regard to this particular design, critics have suggested the influence of pointillism as well as certain works by Paul Klee (1879-1940). Of particular interest, in the 1970s Komai produced many multicolor monotypes, unexpectedly demonstrating an extraordinary chromatic sensibility. Critics have remarked on the influence of Western artists whom Komai greatly admired, such as Odilon Redon, Paul Klee, Max Ernst (1891-1976), and Joan Miró (1893-1983) on many of these copper-plate color prints.

In Komai's oeuvre one senses a constant interplay between reality and illusion. In the monochrome Tsuka no ma no gen'ei ("Labyrinth of Time (B)": 時間の迷路B) of 1952, the dreamlike array of polyhedrons floating in dark space is both ambiguous and beautiful (see the second design on this page). Komai once said, "Dreams and reality. I still don't know which one is the real reality." Nearly 20 years later, Komai's Jikan no gangu ("Time for toys": 時間の玩具) from 1970 attenuates this shadowy sense of illusion with a playful arrangement of brightly colored forms set, once more, against a dark space (see immediately above). Here the mood is more upbeat than in the earlier Labyrinth of Time.

|

| Komai Tetsurô: Untitled, edition 1/1 Etching & grain-printing(?), Fukuhara Yoshiharu (福原義春) collection, 1971 Setagaya Bijutsukan (Setagaya Art Museum: 世田谷美術館), Tokyo |

In the 1970s Komai produced around 120 monoprints. Shown immediately above is an untitled example depicting a house with abstract forms hovering in the space. The rendering of illusions and dreams is intended here, as the realism of the house appears to be in precarious balance with the disquieting forms surrounding it.

Komai produced copper-plate prints until the final year of his life. An example from 1975 titled Bôshi to bin (Hat and bottle: 帽子とビン), in an edition of 60, looks back at the European still-life tradition in a deceptively simple manner (see image below). The technique dispenses with Komai's familiar and often quite complex aquatint and related granular textures, instead resorting to foundational linear etching with cross-hatching to create shadow, volume, and form. It is indeed fascinating that Komai, while celebrated as a great innovator in the world of intaglio prints, never entirely abandoned the most basic of copper-plate techniques, even in the last years of his life.

|

| Komai Tetsurô: Bôshi to bin (Hat and bottle: 帽子とビン) Etchingu (Etching: エッチング), 1975, Ed: 60 (216 x 210 mm) |

Komai played a significant role in the promotion of copper-plate printmaking as an art form in post-war Japan. Through his groundbreaking experimental production of prints, his widespread association with artists, writers, and poets, and his teaching (including appointments at Tama Art University in 1962 and 1970, and at the Tokyo University of the Arts from 1972 to 1976), he became a central figure in the development of intaglio techniques and expressive abstraction, not only in Japan, but also on the international stage.

Works by Koizumi Tetsurô are included in many private and public collections, such as the British Museum, London; Carnegie Museum of Art. Pittsburgh; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Fines Arts, Boston; and National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. © 2020 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo — Catalogue of collections: prints (Tokyo Kokuritsu Kindai Bijutsukan — Shozô-in mokuroku (東京国立近代美術館 • 所蔵品目録). Tokyo: 1993, pp. 145-150, nos. 1357-1410.

- Escande, Marin: "The tape music of Jikken Kôbô 実験工房 (Experimental Workshop): Characteristics and specificities in the 1950s." Proceedings of the Electroacoustic Music Studies Network Conference, Nagoya, September 2017.

- Ishii, Yushihiko (石井幸彦): Jikken kôbô jidai no Komai Tetsurô (実験工房時代の駒井哲郎 Tetsurô Komai in the time of Jikken Kôbô), Jikken Kôbô Experimental Workshop, Tokyo, Tokyo Publishing House, 2013, pp. 234-237.

- Kawakita, Michiaki: Contemporary Japanese Prints. [Trans. by John Bester] Tokyo: Kodansha, 1967, p. 151, nos. 113.

- Sakai, Tetsuo et al.: Mô hitotsu no Nihon bijutsushi kin gendai hanga no meisaku 2020 (Another History of Japanese Art: Masterpieces of Modern and Contemporary Prints 2020: もうひとつの日本美術史近現代版画の名作2020). Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama, 2020, p. 143, no. 8-5.

- Yokohama Museum of Art: Komai Tetsurô: The glittering universe on paper (駒井哲郎:煌めく紙上の宇宙). Reifu Shobô (玲風書房), 2018, exhibition catalog for Tetsurô Komai: A Pioneer of Modern Japanese Copperplate Prints held at the Yokohama Museum of Art, October 13 through December 16, 2018.

Viewing Japanese Prints |