NISHIDA Takeo (西田武雄)

|

Nishida Takeo (西田武雄 1894-1961) was an artist, businessman (ink supplies), art dealer, and publisher. He was born in Mie prefecture and adopted by the Okawa family at the age of five. In 1909, he entered Yokohama Commercial High School (Yokohama Shôgyô Kôkô: 横浜商業高校), and while still in school, one of his watercolors was selected in 1914 for the Eighth Annual Bunten Exhibition (Bunten Rankai: 文展覧会), the official national salon established in 1907 and held in Tokyo; its official name was the Ministry of Education Fine Arts Exhibition (Monbushô Bijutsu Tenrankai: 文部省美術展覧会). In 1918, Nishida entered the Hongô Yôga Kenkyûsho (Hongô Western Painting Institute: 本郷洋画研究所) and studied under one of its two co-founders, the yôga (Western-style art: 洋画) painter Okada Saburôsuke (岡田三郎助 1869-1939). At the same time, he was introduced by Okada to the artist and teacher Yuki Rinzô (結城林蔵) with whom he studied copper-plate printmaking at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (Tokyo Bijutsu Gakkô: 東京美術学校).

|

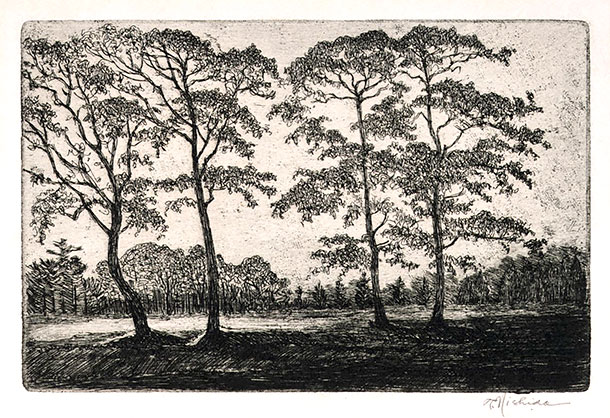

| Nishida Takeo: Four Trees, c. 1924 Etching, 108 x 181 mm (Used later for the first issue of Nishida's Etchingu, November 1932) |

In 1924, Nishida established the Etching Institute (Etchingu Kenkyûsho: エッチング研究所) sometimes referred to as the Nihon Etchingu Kenkyûsho (Japan Etching Research Institute, 日本エッチング研究所) where he taught many artists the techniques of intaglio printmaking. He also promoted the art of etching through seminars and symposia held at various venues.

Komai is particularly well known for having published the dôjin zasshi (coterie magazine: 同人雑誌) titled Etchingu ("Etching": エッチング) from November 1932 through June 1943, producing a total of 125 issues. Etchingu (also given as Ecchingu) focused on intaglio art of the West from its launch in 1932 until the outbreak of war with China in 1937. The first issue (shown on the right), with a sheet size of 268 x 198 mm, included a reproduction of Nishida's "Four Trees" from circa 1924 (see image above). One thinks, perhaps, of the Barbizon school (also called the Fontainebleau School) of painting in the mid-nineteenth century, as one of the influences expressed in this landscape. The painter Jean Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875), for one, comes to mind. In particular, the closely observed naturalism of that European style is evident in Nishida's etching.

Komai is particularly well known for having published the dôjin zasshi (coterie magazine: 同人雑誌) titled Etchingu ("Etching": エッチング) from November 1932 through June 1943, producing a total of 125 issues. Etchingu (also given as Ecchingu) focused on intaglio art of the West from its launch in 1932 until the outbreak of war with China in 1937. The first issue (shown on the right), with a sheet size of 268 x 198 mm, included a reproduction of Nishida's "Four Trees" from circa 1924 (see image above). One thinks, perhaps, of the Barbizon school (also called the Fontainebleau School) of painting in the mid-nineteenth century, as one of the influences expressed in this landscape. The painter Jean Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875), for one, comes to mind. In particular, the closely observed naturalism of that European style is evident in Nishida's etching.

After the start of the war, Etchingu became a pawn of the nationalistic war effort. In the preface to the December 1941 issue, Nishida asserted that Japanese artists must work hard to triumph in the world of art just as Japanese soldiers were trained to win on the battlefield. Nishida declared that the art of the West had already collapsed and so, as a result, Japanese artists had to find their own creative identities. By then the magazine had already begun featuring artists who had fought on the frontlines. The propagandist Patriotic Society of Japanese Art required membership of all artists, coordinated all art groups, and controlled all exhibitions (starting in 1944). The Patriotic Society also selected the Japan Print Service Society as the organization for monitoring prints to ensure compliance with the nation's militarist ideology. Moreover, the para-fascist Imperial Rule Assistance Association (IRAA, Taisei Yokusankai, 大政翼贊會) designated Etchingu as its official mouthpiece in May 1943. After the magazine ended operations in June 1943, Etchingu was revived and renamed Nihon hanga (Japan Prints: 日本版画). However, when it was ordered to incorporate three other magazines, the burden became too much and Nishida ceased publication in February 1944 (see Newland ref. below).

Nishida's etchings focused mainly on landscapes and figure studies. An early work depicting six trees (see image below) appears to have set the stage for his 1924 etching of four trees shown above. However, rather than the calm scene evident in the Four Trees, here the linework is brisk and agitated, especially in the whirling currents of air in the sky. Again, the Barbizon artists seem to have had some influence here, but there is also a touch of Rembrandt in this landscape, an artist whom Nishida no doubt greatly admired.

|

| Nishida Takeo: Six Trees, 1920 Etching, 117 x 165 mm |

Nishida's figure prints often have a foothold in genre scenes or the figures that one could easily find therein. His portrait of a woman from Okazaki (Okazaki fujinzô: 岡崎婦人像) dates from the next decade (1937). Nishida captured a sense of strength or resilience through the firmly etched lines, modeling of the face, and rendering of the shadows. The likeness seems to be drawn from life, and, indeed, it seems true to life.

A genre scene reminiscent of the subject matter found in Barbizon paintings and prints, although not in technique, was completed in 1938 (see image below right). Referred to simply as Nôfu (Farmers: 農夫), the approach is bolder, with thicker, more deeply etched lines than in the Six Trees.

|

_310w.jpg) |

| Nishida Takeo: Okazaki fujinzô (岡崎婦人像) Woman from Okazaki, 1937 (254 x 258 mm) Etching and drypoint (エッチング ● ドライポイント) |

Nishida Takeo: Nôfu (Farmers: 農夫) Etching (エッチング), 1938 (114 x 132 mm) |

Nishida was an important figure for the second generation of sôsaku hanga ("creative print": 創作版画) artists emerging in the 1920s and 1930s. Many artists, most unknown today, were trained in copper-plate printmaking under Nishida's guidance. Some engaged with the technique for a time, then moved on to other modes of art. Others dedicated much or all of their careers to the art of etching. One of the notables in the first category was Koizumi Kishio (1893-1945), who attended Nishida's course on etching and produced a small number of intaglio works.

A leading artist who incorporated intaglio prints along with woodcuts, lithographs, and collagraphs throughout his career was Sekino Jun'ichirô (1914-1988). He admired the etchings of Nishida, even when still in his teenage years, calling the works his "guiding lights." Moreover, Sekino recognized the influence of Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), Anders Zorn (1860-1920), and James Whistler (1834-1903). He remembered seeing the June 1933 issue (no. 8) of Nishida’s magazine Etchingu with his print Yoru no fumikiri ("Evening crossing" or "Rail crossing at night": 夜の踏切), which was illustrated on the first page. The work featured an expressively etched illumination from two lamps high up on poles at the rail crossing. Sekino reported that, "Having only known woodblocks [mokuhan, 木版] up until that point, I was completely consumed by the charm of etchings. I purchased a small press, some tools and materials from Nishida's Etching Institute, and I transformed into a young man smothered by the froth of nitric acid." Sekino also attended a symposium hosted by Nishida, who when he saw Sekino's work, encouraged the young artist to submit his etching of Aomori Harbor to the Imperial Art Academy Exhibition (Teikoku Bijutsu Tenrankai: 帝國美術展覧會), the official salon in Tokyo that replaced the Bunten in 1919.

As with Sekino, the copper-plate artist Komai Tetsurô (1920-1976) first encountered the basic techniques of copper-plate etching in Nishida's magazine Etchingu. That experience provided a direct gateway, or as Komai said, "I entered the art world when I started making copper-plate prints, without first doing any other drawing or painting." Around this time, in 1934-35, he joined Nishida's Etchingu Kenkyûsho where he began learning copperplate printing techniques and was introduced to the works of other artists experimenting with intaglio printmaking. Komai went on to become one of the central figures in intaglio printmaking in Japan. It is likely that Komai befriended Sekino at the institute.

Nishida Takeo is mostly unknown in the West, but his impact on intaglio printmaking in both traditional and experimental modes was significant for the artists of the sôsaku hanga movement. His own prints were inspirational to these artists, and while these etchings may not receive much recognition today, their impact was decisive in the development of printmaking in Japan. © 2020 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Chiba-shi Bijutsukan (Chiba City Art Museum: 千葉市美術館): Nihon no hanga 1921-1930 ( Japanese prints 1921-1930), Vol. III, 2001, p. 83, nos. 138; and Nihon no hanga 1931-1940 ( Japanese prints 1931-1940), Vol. IV, 2004, p. 85, nos. 150-152.

- Sekino, "Kon Junzô," in: Waga hangashitachi: Kindai Nihon hanga kaden (My printmaking teachers: Biographies of modern Japanese print artists: わが版画師たち : 近代日本版画家伝). Tokyo: Kodansha, 1982, pp. 111-112.

- Kaji Sachiko (加治幸子): Sôsaku hanga-shi no keifu 1905-1944 (Genealogy of creative print magazines 1905-1944: 創作版画誌の系譜). Tokyo: Chûôkôron Bijutsu Shuppan (中央公論美術出版), 2008. pp. 696-754.

- Sakai, Tetsuo et al.: Mô hitotsu no Nihon bijutsushi kin gendai hanga no meisaku 2020 (Another History of Japanese Art: Masterpieces of Modern and Contemporary Prints 2020: もうひとつの日本美術史近現代版画の名作2020). Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama, 2020, p. 119, no. 7-15.

- Uhlenbeck, C., Reigle-Newland, A., DE Vries, M.: Waves of renewal: modern Japanese prints, 1900 to 1960. Leiden: Hotei Publishing, 2016, pp. 84-86, 233, 300.

- Yokohama Museum of Art: Tetsurô Komai: A Pioneer of Modern Japanese Copperplate Prints (駒井哲郎:煌めく紙上の宇宙). Reifu Shobô (玲風書房), 2018.

Viewing Japanese Prints |