TOBARI Kogan (戸張孤雁)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tobari Kogan (戸張孤雁 1882-1927), whose family name was Shimura (志村) and given name Kamekichi (亀吉), was born in Tokyo. His first employment was as a clerk for the Japan Bank (Nihon Ginkô) in 1898, when in his spare time he would draw and paint. The following year he also began a study of English at a combination night school and community center operated by the Marxist political activist, journalist, and Christian socialist Katayama Sen (片山潜 1859-1933) who from 1897 to 1901 edited Labor World (Rôdô Sekai, 労働世界). Katayama, having previously spent years in the United States, encouraged Tobari to visit there himself, which he did in 1901, remaining abroad until he contracted tuberculosis and returned to Japan in 1906. It was at that time that he took on work as an illustrator, providing watercolors to be reproduced in novels. Within two years of Tobari's return to Japan, the publisher Hidaka Yûrindô (日高有倫堂) in Tokyo issued in 1908 a book of fiction stories accompanied by Tobari's illustrations titled Collection of Kogan's illustrations (Kogan sôgashû: 孤雁插画集).

|

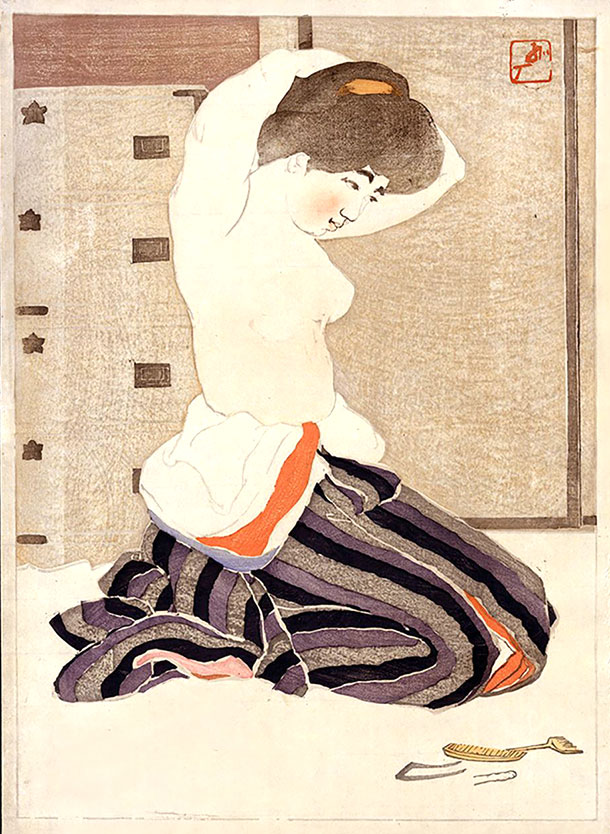

| Tobari Kogan: Keshô (Makeup: 化粧); also called Tansu no mae (In front of the tansu: 箪笥の前) Woodcut, 1913, Artist Seal: Kogan (孤雁); Image: 445 x 318 mm; Paper: 490 x 360 mm |

When Tobari was still in New York, he studied painting, initially privately and then at the National Academy of Design (now called the National Academy School of Fine Arts) and the Art Students' League, both located in Manhattan. He also befriended the sculptor Ogiwara Rokuzan (荻原碌山 1879-1910; real name Ogiwara Morie 荻原守衛), a pioneer in western-style bronze sculpture in Japan, which sparked an interest in Tobari for the medium. When Ogiwara died in Japan in 1910, Tobari felt the loss deeply and resolved to focus on sculpture (see examples at the bottom of this page). He followed up by studying sculpture at the Pacific Art Society. Very early on, one of his sculptures was exhibited at the Bunten (Bunten Rankai: 文展覧会, the official national salon established in 1907 and held in Tokyo; its official name was the Ministry of Education Fine Arts Exhibition, Monbushô Bijutsu Tenrankai: 文部省美術展覧会).

Tobari was a co-founder of the Japan Watercolor Institute (Nihon Suisaiga-kai: 日本水彩画會), established in 1907 in Tokyo along with other artists who had studied in Europe or who had been otherwise influenced by Western art, such as Ôshita Tôjirô (大下藤次郎 1870-1912) and Ishii Hakutei (石井柏亭 1882-1958). In 1918 he also co-founded the Japan Creative Print Association (Nihon Sôsaku-Hanga Kyôkai: 日本創作版画協会), along with quite a number of other artists, such as Yamamoto Kanae, Oda Kazuma, Onchi Kôshirô, Hiratsuka Un'ichi, and Maekawa Senpan. Their aims were to disseminate information on the art of wood carving and engraving, promote the print arts through exhibitions, lobby to have prints exhibited at the Teiten (Salon of the Imperial Art Institute), and establish a Department of Engraving at the Tokyo Academy of Fine Arts. They eventually succeeded in achieving all these objectives. Tobari showed twelve of his prints at the association's first (and most successful) exhibition in January 15-20, 1919, which 20,000 visitors attended at the Mitsukoshi Department Store in Nihonbashi, Tokyo. Twenty-six artists displayed eighty-eight mokuhanga (woodblock prints: 木版画), seventy-eight etchings, nine lithographs, and four monotypes.

|

| Tobari Kogan: Nôka no aki (Farmhouse in autumn: 农家の秋) Also known as Inamura no aki (Autumn at Inamura: 秋xの稲村) Woodcut, 1912 (image: 90 x 135 mm) |

All told, Tobari produced fewer than 20 woodcut designs. There is some speculation that his ongoing struggle with the effects of tuberculosis might have made drawing designs for woodblock prints more appealing than the physically demanding sculpting in clay required for his sculptures, but there appears to be no documentary evidence for this conjecture. His earliest published work appears to have been the peaceful and idyllic "Farmhouse in autumn" (Nôka no aki: 农家の秋), a small-format woodcut from 1912 (shown above). The scene combines Western-style receding perspective with Japanese flattening of depth, particularly in the trees and distant hillside where textures achieved with grain printing (mokumezuri: 木目刷り) also play an important role in the composition. The thatched-roof farmhouse, plainly rendered, marks the middle distance and seems to complement the barn that establishes the end of the foreground space.

One of the most celebrated of Tobari's early works is titled Keshô (Makeup: 化粧) shown at the top of this page — a charming portrayal of a young woman engaged in fixing her hair while kneeling near a chest of drawers (tansu: 箪笥). Tobari combined a traditional pose and voyeuristic gaze familiar in ukiyo-e with a modern sensibility in the rendering of the garments and hair, all of which are printed with light-gray outlines and a soft application of colors that was typically not seen in ukiyo-e (except for certain privately issued prints called surimono, 摺物).

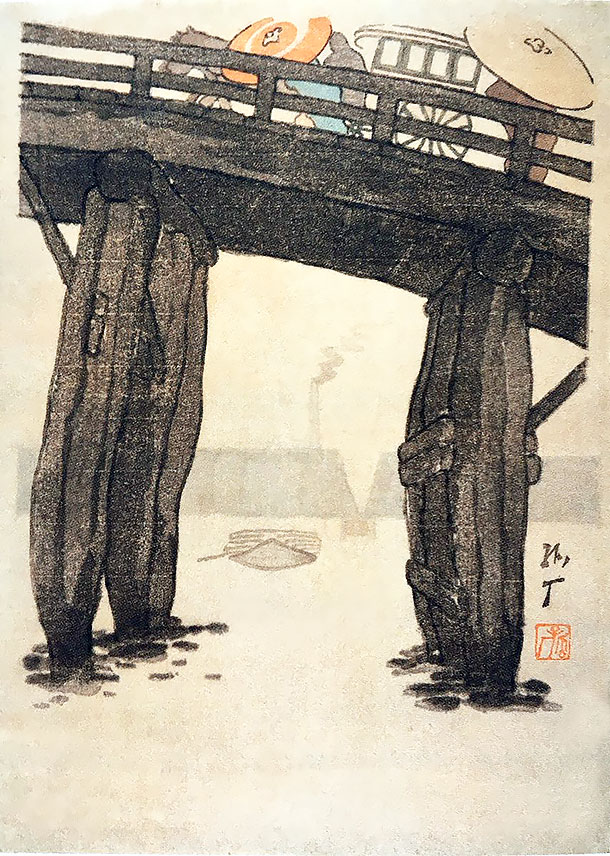

Another notable early work was Tobari's "Great Bridge at Senju in the Rain" (Senju ôhashi no ame: 千住大柏の雨), shown below. This design, perhaps more than any in his oeuvre, has been widely exhibited and illustrated. The eye-catching view introduces a contrast between the foreground "great bridge" and the faint gray forms seen beyond, which include a barge, a factory smokestack, and a modern steel bridge. The expressively textured wooden piers bend with age and decades of carrying pedestrian traffic, which can be glimpsed near the top of the print. One will perhaps recall Utagawa Hiroshige's closeups of bridge piers, as in "Twilight moon at Ryôgoku Bridge (Ryôgoku no yoizuki: 両国之宵月) in his series "Famous places in the Eastern Capital" (Tôto meisho: 東都名所) from 1831 where the scene is also framed by the pillars of a great bridge and the distant sites are seen by looking past massive wooden supports (see small image on the right). Perhaps Tobari was purposely "quoting" from Hiroshige with his modern reworking of the theme.

Another notable early work was Tobari's "Great Bridge at Senju in the Rain" (Senju ôhashi no ame: 千住大柏の雨), shown below. This design, perhaps more than any in his oeuvre, has been widely exhibited and illustrated. The eye-catching view introduces a contrast between the foreground "great bridge" and the faint gray forms seen beyond, which include a barge, a factory smokestack, and a modern steel bridge. The expressively textured wooden piers bend with age and decades of carrying pedestrian traffic, which can be glimpsed near the top of the print. One will perhaps recall Utagawa Hiroshige's closeups of bridge piers, as in "Twilight moon at Ryôgoku Bridge (Ryôgoku no yoizuki: 両国之宵月) in his series "Famous places in the Eastern Capital" (Tôto meisho: 東都名所) from 1831 where the scene is also framed by the pillars of a great bridge and the distant sites are seen by looking past massive wooden supports (see small image on the right). Perhaps Tobari was purposely "quoting" from Hiroshige with his modern reworking of the theme.

|

| Tobari Kogan: Senju ôhashi no ame ("Great Bridge at Senju in the Rain": 千住大柏の雨), Woodcut, 1913 (485 x 356 mm) |

Some of Tobari's works created between circa 1913 and 1918 include an embossed seal reading "Kogan — Association for new brocade prints of the East" (Kogan Shin Azuma nishiki-e Gakai: 孤雁 新東錦絵画会 or close variants), which was an imprint signifying that the artist self-published the particular works, which were, apparently, sold through a "distribution club" (hanpukai: 頒布会). The style of the carving suggests the involvement of professional artisans. Indeed, the artist Ono Tadashige (小野忠重 1909-1990) wrote that Tobari hired block carvers (possibly including Koizumi Kishio, 1893-1945) and printers to supply "mass produced" (ryôsan: 量産) editions of the works under this imprint. These include many if not all of his finest printed works. However, their relative scarcity today brings into question just how many impressions were taken off the blocks.

|

Tobari Kogan: Jogakusei (Schoolgirl: 女学生), or Onna no kao (Face of a woman: 女の顔) |

One of the best-known designs bearing a variant of the aforementioned Shin Azuma Nishiki-e

imprint seal is Tobari's portrait of a young female student (Jogakusei: 女学生) circa 1916-1918 where on some impressions the embossed seal is visible at the lower right (see image above). This portrait, printed with a silver mica background, captures in profile the schoolgirl in the bloom of youth. The contour outlines for the face and neck are strong, while the hair is printed in a soft manner. Fascinating, too, is the omission of the body below the shoulder line, a bust portrait style related to a tradition in Western painting and sculpture dating back to classical antiquity.

One of the best-known designs bearing a variant of the aforementioned Shin Azuma Nishiki-e

imprint seal is Tobari's portrait of a young female student (Jogakusei: 女学生) circa 1916-1918 where on some impressions the embossed seal is visible at the lower right (see image above). This portrait, printed with a silver mica background, captures in profile the schoolgirl in the bloom of youth. The contour outlines for the face and neck are strong, while the hair is printed in a soft manner. Fascinating, too, is the omission of the body below the shoulder line, a bust portrait style related to a tradition in Western painting and sculpture dating back to classical antiquity.

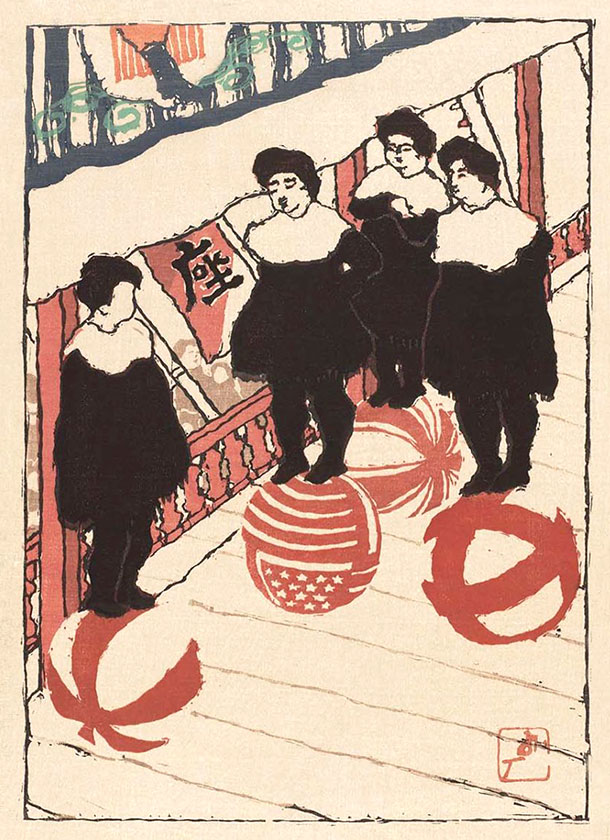

An important design within Tobari's small body of printed work is his playful and eccentric depiction of acrobats shown below. It is one of the most daring compositions within Tobari's oeuvre and is noteworthy in that regard even among all modern Japanese woodcuts during the 1910s (early Taishô era). Three figures are grouped center and right, while an isolated acrobat is placed very near the left edge and closer to the viewer. Between the two pictorial spaces is a banner reading "troupe" or "theater" (za: 座). The performers seem to balance easily upon the large rolling spheres as if they are merely engaged in casual conversation. Tobari dispensed with the outlines for the circus balls, instead printing their decorations only with red pigment, including one with an American flag. The sphere on the right barely reads as such, instead appearing as if it were a cursive kanji character. Tobari used a reduced-size copy of the acrobat design as an example to demonstrate the stages of block-carving and printing in his Sôsaku hanga to hanga no tsukurikata (Creative prints and how to make them: 創作版画と版画の作り方) published in 1922. As is evident from the image on the right, the cover featured Tobari's Jogakusei (Schoolgirl: 女学生), which is discussed above.

|

| Tobari Kogan: Kyokugeishi no tamanori (Acrobats balancing on balls: 曲芸師の玉乗り) Woodcut, c. 1913-14 (387 x 298 mm) |

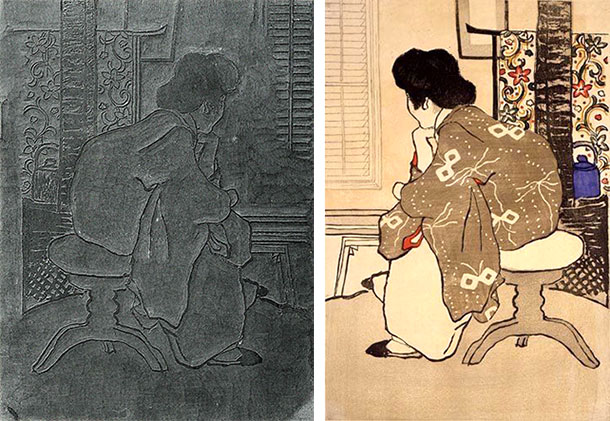

Some of Tobari's original carved blocks have survived. One example from 1919 is shown below for a design referred to as "Artist studio" (gashitsu: 画室) or "Woman in the studio" (Gashitsu no josei: 画室の女性). A seated woman wearing a brown kimono patterned with dye-resist butterflies leans forward as she rests her chin on her right hand. She is perhaps lost in thought and may be she posing for the artist. Behind her is a stove with a bright blue kettle and beyond that is a lacquered kimono rack (ikô: 衣桁) upon which a colorful fabric is hanging. A pencil sketch of this subject also survives, which is close to the finished print, although the lower skirt has a geometric pattern and the outer coat has shading.

|

|

| Tobari Kogan: Gashitsu no josei Woman in the studio: 画室の女性 Carved woodblock, 1919 (approx. 470 × 320 mm) |

Tobari Kogan: Gashitsu no josei Woman in the studio: 画室の女性 Woodcut, 1919 (463 × 301 mm) |

A later excellent landscape by Tobari is his print of Onjuku beach (Onjuku no hama: 御宿の浜) from 1921. Onjuku (御宿) is located on the east coast of southern Chiba Prefecture. Its landscape consists of rolling, sandy hills, and the town is noted for its beach resorts that since 1958 are protected as part of the Minami Bôsô Quasi-National Park (Minami-Bôsô Kokutei Kôen: 南房総国定公園). Tobari's view of Onjuku captures perfectly the sunlit, sandy hills with patches of green grass leading up to a thatched-roof house below a blue sky with cumulus clouds. The cow in the foreground lends a bucolic touch to the scene. Once again, Tobari's "soft" printing style is evident.

|

| Tobari Kogan: Onjuku no hama (Onjuku beach: 御宿の浜) Woodcut, 1921 (269 x 390 mm) |

Many pencil sketches and watercolors are known by Tobari. The Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art in Nagoya alone has an excellent collection of such works totaling 148 works on paper. Most of the drawings are undated but appear to have been made before 1920. The earliest with a secure date is a watercolor of a man wearing a turban from 1903; the latest is the 1919 preparatory watercolor for "Woman in the studio" discussed above. These sketches cover a variety of themes, although a large majority are figure studies (women, circus performers, scenes for novels), and there are a few landscapes. Among these works are five studies of women resting their heads on both arms set upon a table or other surface. Two are shown below.

|

|

| Tobari Kogan: Untitled (Woman resting), undated Watercolor, pencil on paper, (370 x 290 mm) |

Tobari Kogan: Untitled (Woman resting, profile), undated Watercolor , pencil on paper, (380 x 280 mm) |

Tobari Kogan's artistic achievements cannot be judged fairly without considering his sculpture. Tobari's friend and mentor Ogiwara Rokuzan (荻原碌山 1879-1910), mentioned earlier, studied with the great French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) in Paris. When he saw Rodin's full-size casting of "The Thinker" (Le Penseur, 1904) soon after it was completed, he resolved to set aside painting for sculpture. Ogiwara, no doubt, passed on to Tobari his enthusiasm for the Frenchman's modern, radical bronzes of the human figure.

In fact, despite his early death in 1910, Ogiwara was credited with contributing to the so-called "Rodin Boom" (Rodan bûmu: ロダン-ブーム) as Rodin's art become increasingly popular in Japan at the end of the Meiji period (even the conservative Bunten exhibitions acknowledged Rodin). In November 1910, the artist-editors of the art magazine Shirakaba (White Birch: 白樺) published a special issue dedicated to Rodin (269 pages, 26 essays, and 19 illustrations of Rodin's work), who for them embodied the humanism they sought in their lives and work. No European artist was more important than Rodin in helping to inspire Shirakaba's ideological stance on individualism and art. Shirakaba's members sent him a personalized copy and, after pooling their savings, 30 original ukiyo-e prints (including masterpieces by Kitagawa Utamaro, Utagawa Toyokuni I, Katsushika Hokusai, and Utagawa Hiroshige I) for his seventieth birthday. In response, Rodin wrote a letter thanking them and sent three small bronze sculptures (Little Shadow, Head of a Street Urchin, and Bust of Madame Rodin), which are recorded as the first of Rodin’s sculptures to enter Japan (they were exhibited in February 1912 by Shirakaba). As for Tobari's sculptures within this context, his cast bronze of a reclining cat (Neko: 猫, 145 x 409 x 340 mm) was included in the Third Shirakaba Exhibition in November 1911.

In fact, despite his early death in 1910, Ogiwara was credited with contributing to the so-called "Rodin Boom" (Rodan bûmu: ロダン-ブーム) as Rodin's art become increasingly popular in Japan at the end of the Meiji period (even the conservative Bunten exhibitions acknowledged Rodin). In November 1910, the artist-editors of the art magazine Shirakaba (White Birch: 白樺) published a special issue dedicated to Rodin (269 pages, 26 essays, and 19 illustrations of Rodin's work), who for them embodied the humanism they sought in their lives and work. No European artist was more important than Rodin in helping to inspire Shirakaba's ideological stance on individualism and art. Shirakaba's members sent him a personalized copy and, after pooling their savings, 30 original ukiyo-e prints (including masterpieces by Kitagawa Utamaro, Utagawa Toyokuni I, Katsushika Hokusai, and Utagawa Hiroshige I) for his seventieth birthday. In response, Rodin wrote a letter thanking them and sent three small bronze sculptures (Little Shadow, Head of a Street Urchin, and Bust of Madame Rodin), which are recorded as the first of Rodin’s sculptures to enter Japan (they were exhibited in February 1912 by Shirakaba). As for Tobari's sculptures within this context, his cast bronze of a reclining cat (Neko: 猫, 145 x 409 x 340 mm) was included in the Third Shirakaba Exhibition in November 1911.

Unsurprisingly, Tobari became known for his French-inspired bronze figures. As did Rodin and Ogiwara, he sought out naturalistic postures, rejecting idealism or elegance. Two examples (of plaster casts) are shown below. On the left, an expressive standing nude from circa 1914 offers a splendid vision of feminine posture. Slightly slumped and legs turned inward, the figure suggests a balance between relaxation and imminent movement, as if the figure might shift its stance at any moment. Another plaster cast, shown below on the right, presents a nude woman crouching down at the edge of a pond or stream. Titled "Deep water" (Fuchi: 淵), the naturalistic modeling of the female form captures a closely observed moment as the figure dips her right hand below the water's surface. Her calm, concentrated gaze and naturally balanced body make this one of Tobari's finer efforts in three-dimensional realism. Another portrayal of a kneeling nude, also from 1924, is frequently mentioned in discussions about Tobari's sculptures, namely, "Glittering Jealousy" or "Glare of Jealousy" (Kirameku shitto: 煌めく嫉妬), measuring 348 x 200 x 189 mm; see image above right. Here, a woman is bereft of distinguishing facial features, as if a jealous rage (however warranted) has made her unrecognizable. It is one of Tobari's most directly emotional works in sculptural form. Seventy years after this sculpture was made, an exhibition of Tobari's sculptures was held at the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Nagoya, in January 1994 ("Tobari Kogan and Sculpture of the Taishô era," Tobari Kogan to Taishô-ki no chôkoku: 戸張孤雁と大正期の彫刻).

|

|

| Tobari Kogan: Ritsu rafu (Standing nude woman: 立裸婦) Plaster, c. 1914 (395 × 150 × 120 mm) |

Tobari Kogan: Fuchi (Deep water: 淵) Plaster, 1924 (355 × 215 × 260 mm) |

Tobari's prints straddle the worlds of shin hanga and sôsaku hanga ("creative prints": 創作版画). In fact, the inspirational leader of the sôsaku hanga movement, Onchi Kôshirô, found it difficult to place Tobari's works securely in either realm. He considered Tobari's prints to be lacking in serious expressive content, which was one of the ideals in modernist creative printmaking. Onchi thought that Tobari had fallen in love with traditional nishiki-e (full-color ukiyo-e prints) and so compromised the quality of his woodcuts as bona fide shin-hanga ("new prints" or neo-ukiyo-e: 新版画); see Miyama 1994. In Onchi's Contemporary Japanese Prints (Nihon no gendai hanga: 日本の現代版畫) published in 1952 (there is also a 1953 reprint), he chose not to include any illustrations of Tobari's prints. Furthermore, he wrote the following commentary: "Tobari's early work lacks finesse, but there is a soft quality — almost of elasticity — in the carving that is very interesting. His later prints in the series [sic] Shin Azuma Nishiki-e are not very good examples of shin hanga. The designs tended to be too traditional and too conventional. One of his prints — the Senju Ohashi, often seen in the print shops today — has a nishiki-e style with a touch of Art Nouveau added. It is a superficial work and lacks any interior seriousness. Prints of this sort had no influence on and bore no relationship to the modern print movement [sôsaku hanga]. There were no successors to [Tobari's] style, although Koizumi Kishio did some imitations along the same lines." (See Ueda 1965.) Many today would find Onchi's judgment rather harsh and only partly warranted. Onchi was not, of course, considering Tobari's expressive sculptures in his comments. As an advocate for abstract modernism, he valued emotion in printmaking, which he believed could be achieved most directly through self-carved and self-printed works. His reaction to Tobari's "hybrid" approach was therefore understandable.

Impressions of Tobari Kogan's prints are in many public collections, including the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Nagoya; Art Institute of Chicago; British Museum, London; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Honolulu Art Museum, Hawai'i; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian; and National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. © 2020 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Catalogue of Collections [Modern Prints]: The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (Tokyo kokuritsu kindai bijutsukan shozô-hin mokuroku, 東京国立近代美術館所蔵品目録). 1993, pp. 174-175, nos. 1645-1655.

- Chiba City Museum of Art: Nihon no hanga (Japanese prints: 日本の版画), vol. II, 1911-1920. Chiba: 1999, pp. 84-85, nos. 156-160.

- Jenkins, Donald: Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century. Portland Art Museum, 1983, pp. 63-65, nos. 39-41.

- Kogan sôgashû (Collection of Kogan's illustrations: 孤雁插画集). Tokyo: Hidaka Yûrindô (日高有倫堂), 1908.

- Merritt, Helen: Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Early Years. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1990, pp. 138-140.

- Miyama Takaaki (深山孝彰): Kanzô shiryô kenkyû Tobari Kogan no hangi ni tsuite (Research on materials in the museum about Tobari Kogan's woodblocks: 館蔵資料研究 戸張孤雁の版木について). Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Bulletin No. 2, 1994.

- Ono, Tadashige: Kindai Nihon no hanga (Modern Japanese Prints: 近代日本の版画). Tokyo: Sansaisha (三彩社), 1974, p. 28.

- Onchi, Kôshirô: Nihon no gendai hanga (Contemporary Japanese Prints: 日本の現代版畫). Tokyo: Sôgensha, 1952 (1953 reprint).Sakai, Tetsuo et al.: Mô hitotsu no Nihon bijutsushi kin gendai hanga no meisaku 2020 (Another History of Japanese Art: Masterpieces of Modern and Contemporary Prints 2020: もうひとつの日本美術史近現代版画の名作2020). Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama, 2020, pp. 39, 75, nos. 2-5, 5-3.

- Schoneveld, Erin: Shirakaba and Japanese Modernism: Art Magazines, Artistic Collectives, and the Early Avant-garde. Leiden: Brill, 2019, pp. 69, 72-83, 177, nos. 58-66, 146.

- Tobari Kogan: Sôsaku hanga to hanga no tsukurikata (Creative prints and how to make them: 創作版画と版画の作り方). Tokyo: Hangasha, 1922. The cover also has an English title (with spelling errors), "How to Make Prints by Kogan Tohary: Drawn, Blok-Cut & Printed By Author."

- Tobari Kogan to Taishôki no chôkoku (Tobari Kogan and sculpture of the Taishô era: 戶張孤雁と大正期の彫刻): Nagoya: Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, 1994.

- Tobari Kogan sôsaku no kiseki — sashi-e, abura-e, hanga, chôkoku ten. (Tobari Kogan, the source of creativity: Exhibition of illustrations, oil paintings, prints, sculptures: 戸張孤雁 創作の軌跡-挿絵・油絵・版画・彫刻-展). Rokuzan Art Museum (禄山美術館), 2016.

- Taishô risô shugi no kirameki Tobari Kogan to sono nakama-tachi (Sparkle of Taishô Idealism: Tobari Kogan & his companions: 大正理想主義の煌めき • 戸張孤雁とその仲間たち). Rokuzan Art Museum (禄山美術館), 2000.

- Ueda, Osamu and Mitchell, Charles (translators): "Koshiro Onchi, the Modern Japanese Print: An Internal History of the Sosaku Hanga Movement," in: Ukiyo-e geijutsu (Ukiyo-e Art: 浮世絵芸術), Japan Ukiyo-e Society, 1965, no. 11, Special Issue, pp. 3-24.

- Uhlenbeck, C., Reigle-Newland, A., deVries, M.: Waves of renewal: modern Japanese prints, 1900 to 1960. Leiden: Hotei Publishing, 2016, pp. 138-143, nos. 56-61.

Viewing Japanese Prints |