Japanese Gardens (庭)

|

The art of Japanese gardening dates back centuries, and its many forms have been developed and refined until nearly all elements contain both physical and metaphysical significance. The Japanese garden is a subject that many artists have depicted in paintings and prints, and several have specialized in such views. A few sôsaku hanga artists were especially attracted to the patterns and textures of gardens. The result was, for some, a style of design bordering on abstraction. For others, more naturalistic aspects of gardens inspired them in their print designs.

The art of Japanese gardening dates back centuries, and its many forms have been developed and refined until nearly all elements contain both physical and metaphysical significance. The Japanese garden is a subject that many artists have depicted in paintings and prints, and several have specialized in such views. A few sôsaku hanga artists were especially attracted to the patterns and textures of gardens. The result was, for some, a style of design bordering on abstraction. For others, more naturalistic aspects of gardens inspired them in their print designs.

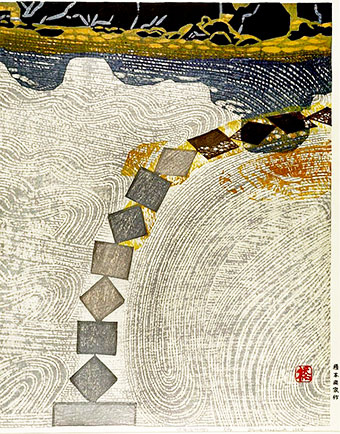

In 1959, Hashimoto Okiie (橋本興家 1899-1993) depicted the sand garden at Konchi-in (金地院), a sub-temple of the Nanzen-ji (南禅寺) complex in Kyoto. The layout of the actual garden has been attributed, with some certainty, to the painter, poet, garden designer, and tea master Kobori Enshû (小堀遠州 1579-1647). Hashimoto's large woodblock print (609 x 489 mm; edition of 50) emphasizes "waves" of sand and a curving line of nobedan (pathway of cut stones: 延段). The rhythm of forms and lines provides much of the impact, while the accent on textures pushes the composition to the edge of abstraction.

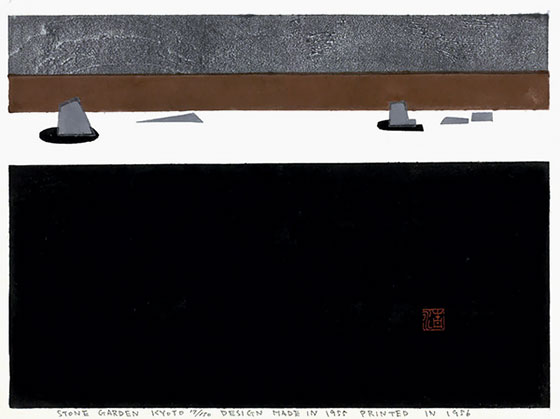

One of Japan's most admired meisho (famous places: 名所) is the rock garden at Ryôanji (龍安寺) in Kyoto, which was rebuilt after being destroyed by fire in 1797. Saitô Kiyoshi (斎藤清 1907-1997) designed a woodcut view of the garden as a bold reduction of forms and abridged-monochromatic severity. A textured gray roof, brown mud wall, mica-covered stones, and black expanse in the foreground have been arranged in a nearly abstract manner. Only a part of the garden is shown; indeed, it impossible to view all 15 stones at once from any angle of the terrace in the actual garden. The mood in Saitô's print is somber and meditative. Saitô self-published this work in an edition of 150, on paper measuring approximately 385 x 527 mm. It is one of the most assertive graphic statements ever made in sôsaku hanga, with the scene and its elements reduced to essentials, and it remains, justifiably, as a symbol of post-war printmaking in Japan.

|

| Saitô: Stone Garden, Kyoto (1955) |

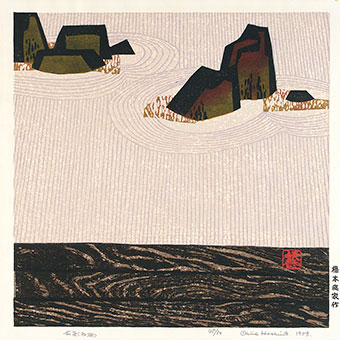

Another example by Hashimoto Okiie is more naturalistic than his Kochi-in woodcut. The title, in Japanese and written in pencil, reads Zentei (Front garden: 前庭) and Sekitei (Rock garden: 石庭). It is from an edition of 50, signed "Okiie Hashimoto" in English, and dated 1958. The block-printed script in the lower right margin reads Hashimoto Okiie saku (Work of Hashimoto Okiie: 橋本興家作).

Another example by Hashimoto Okiie is more naturalistic than his Kochi-in woodcut. The title, in Japanese and written in pencil, reads Zentei (Front garden: 前庭) and Sekitei (Rock garden: 石庭). It is from an edition of 50, signed "Okiie Hashimoto" in English, and dated 1958. The block-printed script in the lower right margin reads Hashimoto Okiie saku (Work of Hashimoto Okiie: 橋本興家作).

The view of the raked sand is represented by parallel verticals that lead into the wave-like ovals surrounding the garden rocks. The lower part of the image was printed with plywood to create a bold grain pattern suggesting a balcony or veranda, which is punctuated by the artist's red seal ("Hashi": 橋) near the right edge. There are multiple perspectives in many of Hashimoto's prints, as here where the flattened frontal view of the plywood contrasts with the more three-dimensional aspect of the sand and rocks. Hashimoto's cropped image of a much wider garden emphasizes movement, form, and texture with subdued tonality, all executed in a refined manner befitting the peaceful setting.

A theme taken up by various modern Japanese artists was the view of a garden seen beyond open doors or screens. A woodcut titled "Mild autumn day" by Kawanishi Hide (川西英 1894-1965) is one such design. A large-format work (image size 456 x 608 mm) from 1958, it depicts, through an open shôji (障子) sliding door or as shadowed forms through the paper on the lattice frames, a tsukubai (stone water basin: 蹲), tobi-ishi (pathway of natural stepping stones: 飛石), ishidôrô (stone lantern: 石灯籠), trees, and large rocks. The simply rendered leaves are reminiscent of the French artist Henri Matisse's "cut-out" forms. These "floating" or "dancing" shapes are consistent stylistic elements in Kawanishi's visual language. For another garden view by the artist, see Kawanishi Hide.

|

| Kawanishi Hide: Koharu biyori (Mild autumn day: 小春日和), 1958 |

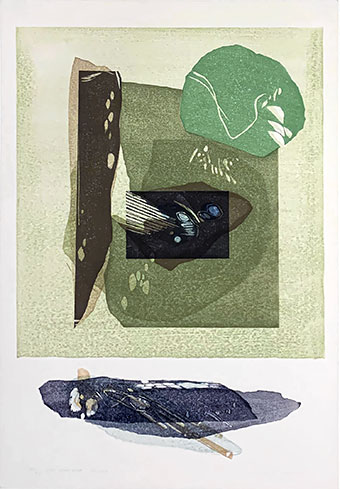

Perhaps no Japanese artist was as steadfast in portraying the forms in gardens as Takahashi Rikio (高橋力雄 1917-1999) who was specifically focused on the classic gardens of Kyoto. He was the son of a Nihonga ("Japanese-style painting") artist, and from 1949-1955 became an important pupil of the seminal figure in modern Japanese printmaking, Onchi Kôshirô (1891-1955), whose late non-representational style had a significant influence on Takahashi.

Pure abstraction was one of the visual currencies taken up by several important sôsaku hanga artists, none more so than than the great advocate for abstraction in Japanese art — Onchi Kôshirô. Onchi's disciple Takahashi was one of the last true sôsaku hanga artists. He repeatedly explored forms, textures, and colors found in gardens and nature, arranging them in an expressive, non-naturalistic manner. He was especially adept at the subtle overlay of colors to create varied opacities and textures and complexity of shapes.

Pure abstraction was one of the visual currencies taken up by several important sôsaku hanga artists, none more so than than the great advocate for abstraction in Japanese art — Onchi Kôshirô. Onchi's disciple Takahashi was one of the last true sôsaku hanga artists. He repeatedly explored forms, textures, and colors found in gardens and nature, arranging them in an expressive, non-naturalistic manner. He was especially adept at the subtle overlay of colors to create varied opacities and textures and complexity of shapes.

The beauty and timelessness of nature are themes underlying Takahashi's particular responses to specific gardens. His designs are animated by a lyrical impulse. The example on the left is a huge work (on paper measuring 915 x 609 mm) titled in pencil "Nunnery" (other impressions have a more complete title, "Nunnery's Garden") from 1975 in an edition of 35, from the artist's "Kyoto Series."

"Nunnery's Garden" is an arrangement of the forms and textures of a garden in a Buddhist convent (called amadera, 尼寺) in Kyoto. The warm greens, browns, and yellows suggest spring or early summer. The natural forms of the layered rocks below contrast with the superimposed shapes above, including rectilinear forms that announce human intervention within the natural world. The composition also relies on multiple perspectives, with some forms seen from above, and others straight on. The shapes have mass, but they occupy space in a manner that is not entirely earth-bound, as though the forms were floating in air.

The print of Ryôanji ("Stone Garden, Kyoto," 1955) by Saitô near the top of this page flirts with total abstraction. Saitô would go on to design various works whose focus on shape, color, and texture said as much about the surface of prints and the process of printmaking as they did about the subject they depicted. Five years after his horizontal view of the stone garden, Saitô depicted the famed Ryôanji again, further flattening the forms to create a predominantly aerial view of a stepping-stone path surrounded by a large wood-grain patterned expanse. It is titled, in English, "Ryôan-ji Kyoto (B)" and dated 1960 in an edition of 200. Instead of adopting a naturalistic view, Saitô has moved close to abstraction, making the rectangular shapes, wood-grain and wall patterns, and overlying textures the main theme of the design. Saitô admired the abstract-geometry paintings of the modernist Dutch artist Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), whose influence seems obvious here.

The print of Ryôanji ("Stone Garden, Kyoto," 1955) by Saitô near the top of this page flirts with total abstraction. Saitô would go on to design various works whose focus on shape, color, and texture said as much about the surface of prints and the process of printmaking as they did about the subject they depicted. Five years after his horizontal view of the stone garden, Saitô depicted the famed Ryôanji again, further flattening the forms to create a predominantly aerial view of a stepping-stone path surrounded by a large wood-grain patterned expanse. It is titled, in English, "Ryôan-ji Kyoto (B)" and dated 1960 in an edition of 200. Instead of adopting a naturalistic view, Saitô has moved close to abstraction, making the rectangular shapes, wood-grain and wall patterns, and overlying textures the main theme of the design. Saitô admired the abstract-geometry paintings of the modernist Dutch artist Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), whose influence seems obvious here.

One modern artist who straddled the worlds of shin hanga and sôsaku hanga was Yoshida Tôshi (吉田遠志 1911-95), eldest son of the pioneering shin hanga printmaker Yoshida Hiroshi (吉田博 1876-1950). While his father was alive, Tôshi worked within the Yoshida family system producing realistic landscapes roughly in the style of his father's works, but with a harder linearity, and lacking the sort of atmospheric romanticism that characterized much of Hiroshi's art. In 1952, when Toshi no longer felt obligated to subscribe to his father's notions of acceptable printmaking, he began a series of abstract woodcuts, influenced by his younger brother, Hodaka Yoshida (吉田穂高 1926-95).

The triptych shown here, however, is an example of the sort of conventional, picturesque realism that he continued to produce throughout his career, even after he had tried his hand at abstract compositions. The three designs were carved and printed in the Yoshida studio, but distributed by the Franklin Mint in the United States. In Asian poetry, art, and culture, the "Plum, Bamboo, and Pine" are called the "Three Friends of Winter" (Ch.: Suihan Sanyou, 岁寒三友 or 歲寒三友圖; Jp.: Sho-Chiku-Bai 松竹梅) because they thrive in winter. The pine and bamboo remain green throughout the cold months, and plum trees are often the first to flower when the weather warms. In Japan, these "friends" are auspicious symbols associated with the start of the New Year. Taken separately, the pine is associated with steadfastness, the bamboo with perseverance, and the plum with resilience.

|

| Yoshida Tôshi: The Friendly Garden (1980) (L to R): Sho or Matsu (Pine: 松), Chiku or Take (Bamboo: 竹), and Bai or Ume (Plum: 梅) |

A contemporary work from 2006 features the garden at Ryôan-ji in a mostly naturalistic manner, although the entire image is printed with a textural effect that lifts the design above the pedestrian. The applications of colors and texturing of the print surface are technically masterful. The artist, Kazuyuki Ohtsu (born 1935), trained in woodblock printing starting in 1954 at the Umehara Hanga Studio in Tokyo, and then, from 1958, he worked as a printer for 40 years for Saitô Kiyoshi, until Saitô's death in 1997. Ohtsu then established his own studio where he began producing his designs. The appealing image below, titled Sekitei — Kyoto Ryôan-ji (Stone Garden — Ryôan Temple in Kyoto: 石庭 京都龍安寺), measures 380 x 580 mm. It offers a straight-on realistic view without the ambiguous perspective seen in other examples on this page, and so it would seem marks a return to conventional meisho, although in a modern stylistic idiom. © 2000-2020 by John Fiorillo

|

| Ohtsu Kazuyuki: Sekitei — Kyoto Ryôan-ji (Stone garden — Ryoan Temple in Kyoto: 石庭 京都龍安寺), 2006 |

This page is dedicated to the memory of Barbara V. Morse, who loved Asian art and owned the impression of Hashimoto's Zentei illustrated above. |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Jenkins, Donald: Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century. Portland, 1983, pp. 102 and 126.

- Kobe City Koiso Memorial Museum of Art: Kawanishi Hide kaiko ten — seitan ichihyakunijû nen (Kawanishi Hide, the retrospective — 120th anniversary of his birth: 川西回顧展 生誕120年). Kobe Shiritsu Koiso Kinen Bijutsukan, 2014.

- Smith, Lawrence: The Japanese Print Since 1900: Old Dreams and New Visions. London, 1983, pp. 119 and 129.

- Smith, Lawrence: Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989. London, 1994, p. 46.

- Statler, Oliver: Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn. Rutland, VT: 1956, pp. 133-136, and dust-jacket illustration.

Viewing Japanese Prints |