TSURUYA Kôkei (弦屋光溪)

The print on the righe, measuring 395 x 249 mm, is from an edition of only 45 impressions on Hodomura paper from Tochigi Prefecture. From Kôkei's third series of bust portraits, it portrays Ichikawa Ennosuke III (三代目 市川猿之助) as the fox Genkurô (Genkurô kitsune: 源九郎狐) in the play Yoshitsune senbon zakura (Yoshitsune and the thousand cherry trees: 義経千本桜) for a performance in 10/1983 at the Kabuki-za, Tokyo. Genkurô disguises himself as Tadanobu, a retainer of the Minamoto (Genji) general Yoshitsune. This was the artist's sixty-second design and arguably his first masterpiece in a highly individual style. The skilled drawing with its delicate flowing lines and determined facial expression, plus the other-worldly colors set against a silver-mica background, capture the essence of the fox taking on human form. Unlike traditional ukiyo-e artists who provided publishers with original drawings for their block cutters and printers, Kôkei draws, carves, and prints his own designs, but with a difference — all but his earliest kabuki subjects (and a few non-theatrical designs) were produced on very thin papers, in particular hodomura from from Tochigi prefecture and ganpi from Kôichi and Fukui prefectures. These papers are very difficult to work with, but their translucent quality imparts an expressive fragility to his works. He often used hô (silver magnolia) for his small editions, a wood that Kôkei says was "neither too hard nor too soft") and thus more easily carved than cherry (sakura) common to ukiyo-e, where often thousands of impressions were taken from the blocks. It took about 25 days to complete an edition (all his editions were small, especially some of the specially commissioned prints that were not sold publicly).

In February 2019, for a retrospective of his works, Kôkei provided a wealth of details about his methods in a video interview (see USC-PAM video still at bottom of this page and ref. * below). He would first sketch the actors' faces from photos in advance of performances. Then, he attended rehearsals for plays in which his selected actors were scheduled to appear. He also attended opening performances, focusing only on the actor he wanted to portray. These visits would provide inspiration for his prints. Typically, he would spend three days on design, four days on carving the blocks, and three days on printing the edition. He gave 10 prints to the Kabuki-za for sale starting around the tenth of the month. Every five days he would present another 10 prints for sale until the final day of performance. So about 30 or 40 prints would be sold at the theater, and then other impressions would be sold to customers who had reserved them through subscription.

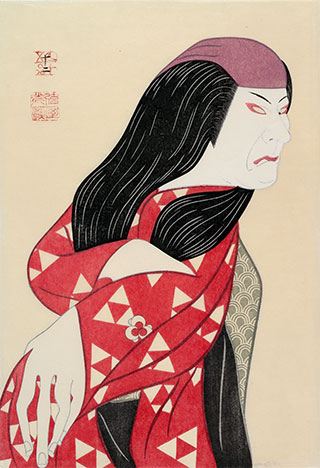

When asked why he used the extremely thin ganpi paper for his prints, Kôkei likes the light brown tone of the ganpi he uses. He also admires the effect that ganpi has on "aging" his colors. Moreover, its thinness is not so very different, he feels, from some of the thin (cheaper) papers one finds with many ukiyo-e. He does admit, however, that he has challenged himself to work with Japan's thinnest paper, which "wrinkles like tissue paper when held." It requires not only moistening, but also stretching as wide as possible before printing to avoid shrinking and misalignment of colors. When he was young, he thought, "Who else in woodblock printing can do this?" He admitted that one could chalk this up to youthful ambition. In regard to his colors, which his admirers consider subtle and expressive, Kôkei has a deep respect for the traditions of kabuki, and for their specific meanings and symbolism. So he feels it was not difficult to decide which colors to use, as he wanted to remain true to what was presented at the Kabuki-za. (One would have to exclude the monochromatic-ink style Kôkei used in 1992-93 and a few times thereafter.) In this regard, Kôkei believes that his creativity can be found in the choice of background colors. The design immediately above right, from Kôkei's fourth series of bust portraits, was issued in November 1984 (edition of 45) on ganpi from Kôichi Prefecture measuring 498 x 372 mm. It depicts the actor Nakamura Utaemon VI as Tonase in Act 9 from the perennially popular kabuki play Kanadehon chûshingura (Writing manual of the treasury of loyal retainers: 假名手本忠臣蔵). Tonase is the wife of the councilor Honzô [see also Shunsen's portrait]. In the scene shown here, Tonase has vowed to take her own life and that of her daughter Konami who has been humiliated in a failed marriage arrangement. She wears her husband's two swords in a symbolic gesture as she prepares for their deaths (which are prevented at the last moment). The use of gofun (calcium carbonate pigment) mimics the opaque white face powder used by the actor. The lines of the face are tense and thin, giving Tonase an air of deadly resolve. The impossibly huge hand grips the sword hilt and serves as an emotional pivot for the design. This treatment of hands is a trademark of Kôkei's style; he has said that "portraits without hands seem strange" and that hand gestures in kabuki often have meaning, which led him to introduce deformation or exaggeration. The crimson of the kimono offers a surprisingly bright note in an otherwise grim portrayal.

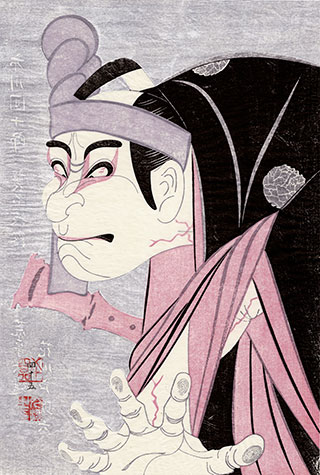

When asked about the comparisons people make between his work and Sharaku's iconic prints from 1794-95, Kôkei admitted that at the start of his career, he wanted to be the "modern Sharaku." which he thought came not from the great works, but from the mystery surrounding an artist whose personal life remains unknown to this day. As Kôkei put it, "For 22 years I hid myself from the public like him." In 1985 Kôkei produced six prints to commemorate the shûmei (succession to the name: 襲名) of Ichikawa Danjûrô XII at the Kabuki-za, Tokyo. They were all included in his fifth series of bust portraits. One such design (see immediately above left) is a portrayal of Danjûrô XII in the role of Hanakawado Sukeroku (花川戸助六) from the play Sukeroku yukari no Edo zakura (Sukeroku: Flower [kinsman] of Edo: 助六由縁江戸桜). It is printed on ganpi from Fukui Prefecture on paper measuring 393 x 265 mm (edition 54). Issued in 6/1985, the role is one of the perennial favorites in kabuki. has been a huge hit with audiences since its premiere in 1713, when Ichikawa Danjûrô II introduced the play, thereby initiating nearly two centuries of intimate association between the play and the Ichikawa acting lineage. In the play, a courtesan named Agemaki, who loves Sukeroku, is being pursued by Ikyû, an elderly samurai whom she detests. Various intrigues and conflicts follow, until, in the end, Sukeroku murders Ikyû for stealing an heirloom sword. Sukeroku makes his escape over brothel rooftops, knowing that he will rendezvous with Agemaki. Kôkei's design graced the cover of the catalog raisonné of his 200 kabuki prints made from 1978 until 2000 (see the Shôchiku Co., 2000 ref. below).

The design below left is one of Kôkei's privately commissioned prints (for the American print dealer William Pinckard) on ganpi tori no ko paper from Fukui Prefecture measuring 383 x 239 mm (edition of 63; December 1988). It portrays the actor Nakamura Kichiemon II as Kinoshita Tôkichi in the play Gion sairei shinkoki (Gion Festival chronicle of faith: 祇園祭礼信仰記) and, more specifically, the Kinkakuji no ba (The Golden Pavilion scene). Tôkichi was a retainer plotting to rescue the late shogun's mother from the evil Daizen. The two play a game of go, which Tôkichi wins, whereupon Daizen throws the box of go counters down a well and challenges Tôkichi to retrieve it without wetting his hands. Tôkichi diverts water from a waterfall into the well and floats the box to the top, lifts it with his fan, and sets it upon an overturned go board. The actor is portrayed against a purple-pink mica ground, and the curving lines of Kôkei's earlier works have changed here to more angular and straighter lines in the face, giving the portrait a quality of rigid confrontation. Once again the enlarged and distorted hand serves as a focal point for the composition and the soft-edge printing is quite effective.

Kôkei ceased designing kabuki prints in 2000 (the catalogue raisonné cited below illustrates 200 woodblock prints by the artist). Then, after seventeen years and the creation of about 100 self-portraits, Kôkei returned to printmaking, although at a far less frequent pace than before. Given his admiration for ukiyo-e portraits, Kôkei began a small series of imaginary portraits of ukiyo-eshi (master artists of floating world prints: 浮世絵師) in 2017. Titled Banzai ukiyoe-ha gosugata ("Long live five figures of ukiyo-e": 万歳浮世絵派五姿), and designed in the spirit of commemorative portraits, the print series includes, as of December 2020, Hokusai (2017), Kuniyoshi (2018), Hiroshige (2019), and Kunisada (2020). Kôkei stated that he used the word "banzai" (万歳) in the title to to mean "eternal prosperity," acknowledging the lasting fame and influence of the earlier masters.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

|

Viewing Japanese Prints |

_320w.jpg)