MUNAKATA Shikô (棟方志功)

|

Munakata Shikô (棟方志功) was once described by the novelist Jun'ichirô Tanizaki as "an impertinent artist who gouges the universe." Today, Munakata is recognized internationally as legendary figure of astounding energy and sensitivity. Munakata's work was influenced by the Buddhist folk tradition of Japan, but his vision was also distilled through his personal expression of Zen Buddhism and the spirit of Shintô combined with elements of mingei (folk craft).

Munakata Shikô (棟方志功) was once described by the novelist Jun'ichirô Tanizaki as "an impertinent artist who gouges the universe." Today, Munakata is recognized internationally as legendary figure of astounding energy and sensitivity. Munakata's work was influenced by the Buddhist folk tradition of Japan, but his vision was also distilled through his personal expression of Zen Buddhism and the spirit of Shintô combined with elements of mingei (folk craft).

Munakata was moved by what he called the "power of the board." He even used a different first character when calling his prints hanga, his version translating into something more like "board picture" than the standard term (which is closer to "print picture"). Thus, by calling his prints itaga ("board pictures" or "woodblock art": 板画) instead of hanga (block prints: 版画), he emphasized the wood itself as the source of the art rather than the process of printing from wood. He said, "When I first made hanga, I used the usual character, han [print: 版], but when I understood the true meaning of hanga, it had to be hanga that maintained the importance of being brought to life from the board. I realized that, for me, it was no good unless the spirit of the wood was being born. Because I heard the voice of the board, I decided to use the character for 'board' [ita]."

Munakata believed that the artist must succumb to the power of the board. He worked at great speed, as if the form had to be released from within the board before it dissipated. He said, "My line must be executed in one quick and spontaneous stroke, as I do not believe in retouching. For the work to be fully animated, one's fresh and raw energy must be shown."*

Munakata began painting in oils after seeing reproductions of works by Vincent Van Gogh around 1921; the Dutch genius would prove to be a life-long inspiration. He took some instruction from his friend Kihachirô Shimozawa (下澤木鉢郎 1901-1984 or 86?), a Western-style oil painter, watercolorist, and, starting the 1930s, print designer who was from Aomori but later based in Tokyo (Munakata followed his teacher there in 1924).

Munakata was attracted to prints, however, when, in 1926, he saw "Early Summer Breeze," a woodcut by Kawakami Sumio. The lightly hand-colored print depicted a woman in Western dress holding a parasol. On the right of the figure, Kawakami had inscribed a poem of his own. Munakata was inspired by the beauty of the design as well as by the poem. Munakata later said that, "I was fumbling with color prints until one day I saw a woodcut by Sumio Kawakami. It was black and white, a small work showing a woman walking in the wind, with a poem about the wind of early summer. Suddenly I knew I had found what I was looking for. Kawakami had shown me the way. I threw myself into prints." [see Yasuda and Statler refs.] While most artists worked with professional grade carving knives, Munakata favored inexpensive children's tools. As they became dull, he simply replaced them with a new set, refusing to waste a moment of inspiration sharpening knives. He relied on a straight chisel for sharp lines and a curved chisel for soft-edge lines or forms. He also used ordinary sumi for his black ink, the cheapest he could find, and printed on thin, unsized kôzo paper (楮紙) or izumo paper (出雲紙). [see Statler ref.]

Munakata wrote articles for the coterie magazine Han geijutsu (Print Art, 版芸術) beginning in 1932, which brought him into contact with Maekawa Senpan and the folk style. In March 1932 a special issue of the magazine was devoted entirely to his work (see cover below left). Around this time he came to know writers and poets such as Yasuda Yôjûro (保田与重郎 1910-1981) and to design books for them. Yasuda, in turn, edited a small book on Munakata produced by the C.E. Tuttle company in 1958 (the English was provided by Oliver Statler). His meeting in 1936 with Yanagi Sôetsu (柳宗悦 1889-1961), the guru of the Folk Art Movement, and its preeminent potters Hamada Shôji (濱田庄司 1894-1978) and Kawai Kanjirô (河井寬次郎 1890-1966) boosted his confidence in his "folk-craft" or mingei (民芸) style, and on a long visit to Kawai's house that year he developed a Buddhist dimension to add to his already strong folk and Shinto interests and subject-matter.

Munakata saw himself as a temporary medium through which the design, not really his own, could be revealed. He rarely composed preliminary sketches. As a result, his prints have spontaneity and spiritual energy. His first works were published in 1928, and by 1935 he had become more widely recognized for his unusual talent and personality. He was the third Japanese print artist to win an international print-competition honor when he was awarded the "Prize of Excellence" at the Second International Print Exhibition in Lugano, Switzerland in 1952. (Saitô Kiyoshi and Komai Tetsurô, 1920-76, had won prizes at the First Sao Paulo Biennale in 1951.) Munakata was the first Japanese artist to be awarded a grand prize in international competition when he secured that honor at the Third Sao Paulo Biennale in 1955 for three of the panels in his Ten Great Disciples series; see example above right). He won another Grand Prix at the 28th Venice Biennale in 1956. For his achievements in art, Munakata received the Medal of Honor (Hôshô, 褒章) with blue ribbon in 1963 from the Japanese government, and then the government granted him its highest honor in the arts, the Order of Culture (Bunka-kunshô, 文化勲章), in November 1970, conferred by the Emperor of Japan.

Munakata saw himself as a temporary medium through which the design, not really his own, could be revealed. He rarely composed preliminary sketches. As a result, his prints have spontaneity and spiritual energy. His first works were published in 1928, and by 1935 he had become more widely recognized for his unusual talent and personality. He was the third Japanese print artist to win an international print-competition honor when he was awarded the "Prize of Excellence" at the Second International Print Exhibition in Lugano, Switzerland in 1952. (Saitô Kiyoshi and Komai Tetsurô, 1920-76, had won prizes at the First Sao Paulo Biennale in 1951.) Munakata was the first Japanese artist to be awarded a grand prize in international competition when he secured that honor at the Third Sao Paulo Biennale in 1955 for three of the panels in his Ten Great Disciples series; see example above right). He won another Grand Prix at the 28th Venice Biennale in 1956. For his achievements in art, Munakata received the Medal of Honor (Hôshô, 褒章) with blue ribbon in 1963 from the Japanese government, and then the government granted him its highest honor in the arts, the Order of Culture (Bunka-kunshô, 文化勲章), in November 1970, conferred by the Emperor of Japan.

According to Oliver Statler (ref. below), Munakata used a straight chisel for hard lines and a curved chisel for softer ones. He held his chisel like a brush or pencil and turned the block (solid katsura, 桂) as he worked. Statler quoted Munakata, who said, "The choice of wood shows the character of the artist. Hô (magnolia, 朴) spreads as you cut it so that the chisel runs easily. Katsura is tougher and as it's cut, it pinches the tool, so that it gives me some resistance."

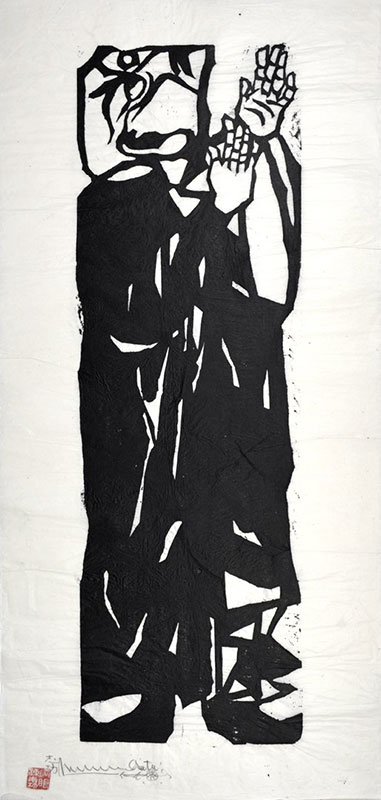

The image at the top right, carved in 1939, portrays Ubari no saku (Upāli, 優波離) from the series Nibosatsu shaka jûdai deshi (Two bodhisattvas and ten great disciples of Sakya: 二菩薩釈迦十大弟子). The set of 10 disciples (plus the two bodhisattvas) was conceived as a six-fold screen (two images on each leaf). During World War II, Munakata used the original blocks from this series to shore up the walls of an air-raid shelter he had excavated in his backyard. Although his house was destroyed by bombing in 1945, and most of his other woodblocks were burned, the disciples survived. Upāli was an expert in monastic discipline and monastic code. He attained the state of arhatship (one who has achieved nirvana) before his death, and is regarded as the "patron saint" of monks who specialize in the Vinaya (rules and procedures that govern the Buddhist monastic community). Munakata's large (923 x 282 mm) portrayal of Upāli is carved forcefully into the woodblock, cutting off edges of the figure as it presses against the confines of the board. With this placement (or "release" of the figure from the block), Munakata achieved something special — the board served not merely as a matrix for the design but became a part of the composition.

In many early works, Munakata added colors by hand on the front surface of the prints, but he found it obscured the black keyblock lines, ruining the design. Around 1945, the aforementioned Yanagi Sôetsu, head of the Japan Folk Art Museum in Tokyo, and art critic, philosopher, and founder of the mingei (folk art: 民芸) movement in Japan in the late 1920s and 1930s, suggested coloring from the verso and allowing the pigments to bleed through to the front. Munakata was quite pleased with the results and called the technique urazaishiki ("back-coloring: 裏彩色). He would incorporate this type of coloring whenever he believed using only sumi (black) pigment did not achieve the particular feeling he desired in a design.

In 1945, just after the end of the war, Munakata produced another important set on a Buddhist theme, this time 24 images (20 were female) intended to be mounted as a pair pf six-fold screens (two images on each leaf). Titled Shôkei shô hangakan (Print volume in praise of Shôkei: 鐘渓頌版画巻), the series was a tribute to Munakata's friend and supporter in the Mingei (Folk Art: 民芸) movement, Kawai Kanjirô (河井寬次郎 1890-1966), one of Japan's great twentieth-century potters (who refused all official honors, including the designation of Ningen Kokuhô 人間国宝, Living National Treasure). Kanjirô's self-made, eight-chamber kiln in the Gojô district of Kyoto was called "Shôkei'"(Valley of the Bell: 鐘渓). Munakata showed 12 of the 24 prints at the aforementioned Third Sao Paulo Biennale in 1955.

In 1945, just after the end of the war, Munakata produced another important set on a Buddhist theme, this time 24 images (20 were female) intended to be mounted as a pair pf six-fold screens (two images on each leaf). Titled Shôkei shô hangakan (Print volume in praise of Shôkei: 鐘渓頌版画巻), the series was a tribute to Munakata's friend and supporter in the Mingei (Folk Art: 民芸) movement, Kawai Kanjirô (河井寬次郎 1890-1966), one of Japan's great twentieth-century potters (who refused all official honors, including the designation of Ningen Kokuhô 人間国宝, Living National Treasure). Kanjirô's self-made, eight-chamber kiln in the Gojô district of Kyoto was called "Shôkei'"(Valley of the Bell: 鐘渓). Munakata showed 12 of the 24 prints at the aforementioned Third Sao Paulo Biennale in 1955.

The series was Munakata's first after the Pacific War. Each print was about 455 x 327 mm and hand-colored from the back. Munakata initially used the technique of urazaishiki ("back coloring": 裏彩色), a term associated with paintings, in 1938 when he brushed colors on the back of 12 prints in his series Kannon-gyô hangakan (Print volume of the Kannon Sûtra: 観音経版画巻) In the Shôkei series, each contorted figure virtually fills the picture space as flat black forms whose details (heads, torsos, limbs) were engraved or gouged out in reserve, apparently the first time the artist used this technique; it became a signature method for the remainder of his career. These bold "white" lines were for the most part hand-colored on the reverse in blue, purple, or tan, allowing the fluid colors to bleed through the paper to the front. The example immediately above is titled Raimon no saku (Thunderbolt pattern: 雷紋の柵).

One of Munakata's masterpieces is a 14-section wall-size (1,320 x 1,580 mm) woodcut portraying hunters on horseback, along with dogs and game birds, racing through a field of flowers. Despite the postures of the hunters suggesting they should be shooting animals with bows and arrows, there are, in fact, no weapons, nor even harnesses on the horses. The print design is titled Hanakarishô (In praise of flower hunting: 華狩頌). Inspired by a photograph of a hunting-scene mural-painting from a fifth-century tomb in Jilin Province, China, as well as by a Japanese ritual in which flowers are used as symbolic arrows, Munakata said about this print that, "The hunters are after flowers, and so must hunt with their hearts."

|

| Munakata: Hanakarishô (Flower hunting: 華狩頌), 1954 Woodcut, 1,320 x 1,580 mm |

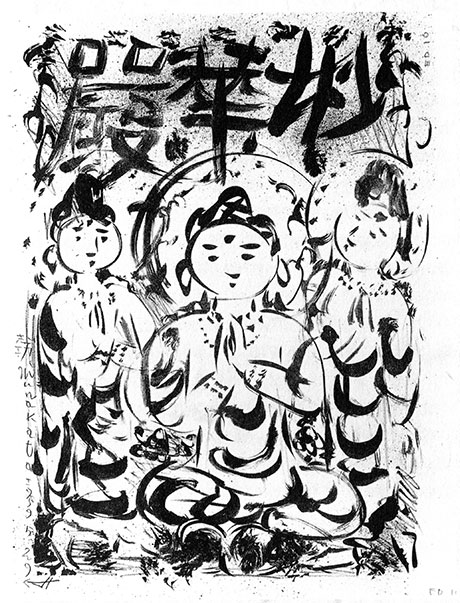

During a one-week visit to Philadelphia in 1959, Munakata worked with Arthur Flory (1914-1972), a graphic artist and author/illustrator of children's books who was head of the Graphics Department and an instructor of graphics, printing, and drawing at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University. Quickly learning the techniques of lithography from Flory, Munakata explored the medium by creating a group of seven lithographs: two works of Buddhist figures, two prints of nudes, and one each of owls, calligraphy, and a scene of a large apple tree outside Flory’s studio. An example is shown below, called "Buddhist Triad" (Shaka mimasu zo zu: 釈迦三益像図), 539 x 393 mm. The collaboration was an invigorating and productive experience, and the two artists remained friends thereafter. They worked together the following year when Flory received a Rockefeller Foundation Grant sanctioned by the Japan Society to teach lithography in Japan. Flory supervised the workshop in Shinjuku, Tokyo, where he interacted with forty-two artists, producing sixty-four designs in editions of fifteen to twenty impressions. On November 10, 1960, Flory, who like many others was amazed by the speed at which Munakata worked, wrote: "Munakata came this morning and knocked off four stones."

Munakata's prints have a distinctive spontaneity and spiritual energy. He saw himself as a temporary medium through which the design, not really his own, could be revealed. As a result, unlike Onchi Kôshirô and other artists of the sôsaku hanga (creative print: 創作版画) movement who advocated self-expression in their printmaking, Munakata disclaimed individual responsibility as an artist. For him, artistic creation was only one of many manifestations of nature's force and beauty, which is inherent in the woodblock. In Munakata's words, "The essence of hanga lies in the fact that one must give in to the ways of the board ... there is a power in the board, and one cannot force the tool against that power."

Munakata's prints have a distinctive spontaneity and spiritual energy. He saw himself as a temporary medium through which the design, not really his own, could be revealed. As a result, unlike Onchi Kôshirô and other artists of the sôsaku hanga (creative print: 創作版画) movement who advocated self-expression in their printmaking, Munakata disclaimed individual responsibility as an artist. For him, artistic creation was only one of many manifestations of nature's force and beauty, which is inherent in the woodblock. In Munakata's words, "The essence of hanga lies in the fact that one must give in to the ways of the board ... there is a power in the board, and one cannot force the tool against that power."

On November 17, 1975, in the year of his death, the Munakata Shikô Memorial Hall [Museum of Art] (Munakata Shikô Kinenkan: 棟方志功記念館) opened in Aomori, Japan, the artist's home city. The building is a two-floor, iron-rebar structure done in a log-cabin or "school-house" style. The museum has the largest number of Munakata's works in Japan. Its collection includes woodcuts, lithographs, sumi-ink paintings (some also with colors) on paper and boards, oil paintings, calligraphy, illustrated books, and original carved wood planks. More than 700 items are rotated in four exhibits per year, although Munakata's aforementioned masterpiece Nibosatsu shaka jûdai deshi is always on display in the Memorial Hall.

Munakata's works are in numerous private collections and in public institutions, including the Art Gallery of New South Wales; Art Institute of Chicago; Asian Art Museum, San Francisco; British Museum, London; Brooklyn Museum, New York; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Cincinnati Art Museum; Detroit Institute of Art; Fine Art Museums of San Francisco; Harvard Art Museums; Honolulu Museum of Art; Japan Folk Art Museum, Tokyo; Los Angeles County Museum of Art;Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Minneapolis Museum of Art; Munakata Shikô Memorial Museum of Art; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; National Museum of Asian Art (Smithsonian), Washington, D.C.; National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto; National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; Philadelphia Museum of Art; and Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. © 1999-2022 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Castile, Rand: Shikô Munakata: Works on Paper. New York: Japan Society, 1982.

- Hisae, Fujii: Shikô Munakata ten (Exhibition of Munakata Shikô: 棟方志功展). Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art, 1985.

- Jenkins, Donald: Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century. Portland: Portland Art Museum, 1983, pp. 106-110.

- Kawai, Masatomo, et al.: Munakata Shikô: Japanese Master of the Modern Print. Philadelphia Museum of Art and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2002.

- Kung, David: The contemporary artist in Japan. Honolulu: East-West Center Press, 1966, p. 155.*

- Munakata Shikô Kinenkan (Munakata Shikô Memorial Hall, 棟方志功記念館): https://munakatashiko-museum.jp/en/career/

- Sakai, Tetsuo et al.: Mô hitotsu no Nihon bijutsushi kin gendai hanga no meisaku 2020 (Another History of Japanese Art: Masterpieces of Modern and Contemporary Prints 2020: もうひとつの日本美術史近現代版画の名作2020). Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama, 2020, pp. 140-141, no. 8-2.

- Smith, Lawrence: The Japanese Print since 1900: Old dreams and new visions. London: British Museum Press, 1983, pp. 47, 51, 54.

- Stanley-Baker, Joan: Mokuhan: The Woodcuts of Munakata & Matsubara. Victoria, BC: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1976.

- Statler, Oliver: Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn. Rutland: Tuttle, 1956, pp. 70-88 and 196-197.

- Yanagi, Sôri: The Woodblock and the Artist: The Life and Work of Shikô Munakata. Tokyo & New York: Kodansha, 1991.

- Yasuda, Yojûrô and Statler, Oliver: Shiko Munakata. Rutland VT: 1958, p. 70.

Viewing Japanese Prints |